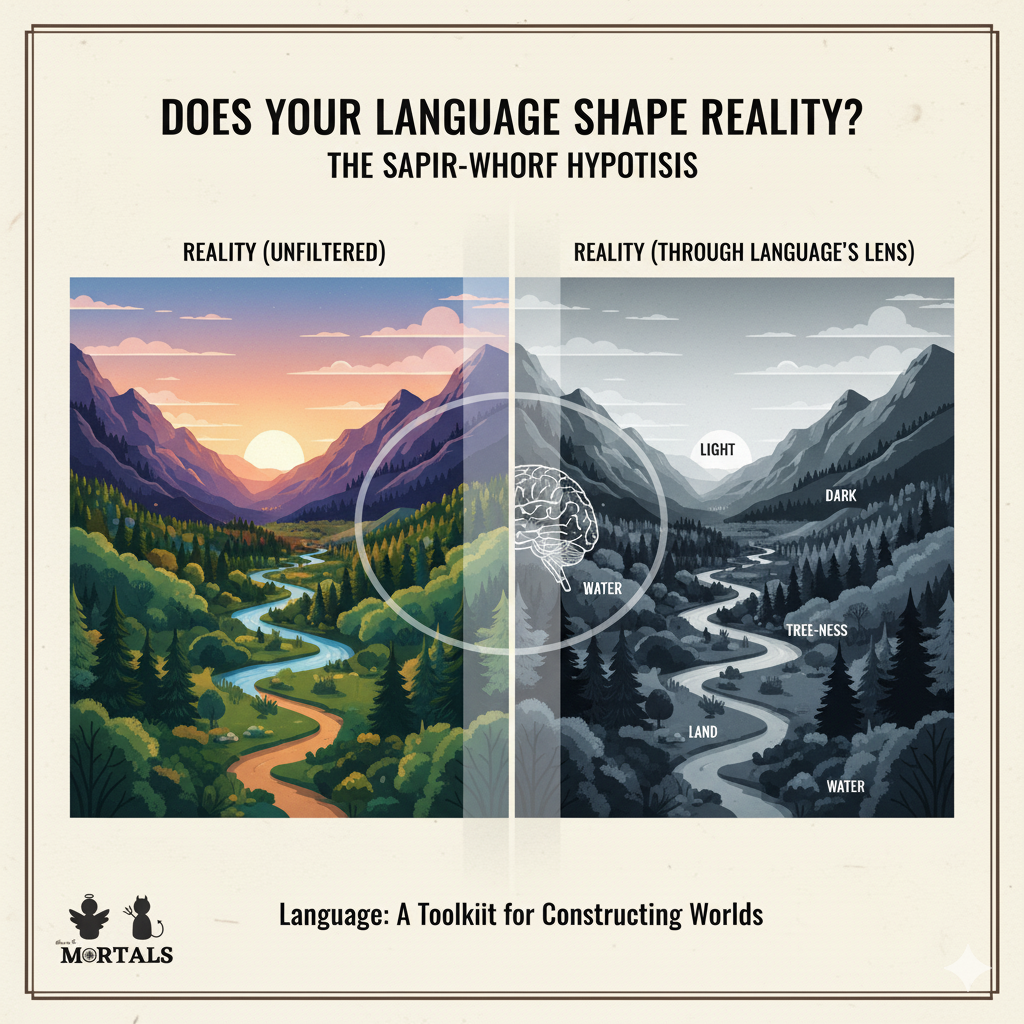

Imagine a language with no words for “yesterday” or “tomorrow,” or one that forces you to specify whether an event was witnessed firsthand or heard as a rumour every time you speak. Would the speakers of such languages experience time and truth in the same way that we do? This is the puzzle at the heart of the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis. In the early 20th century, two brilliant linguist-anthropologists proposed the radical idea that language is not just a tool for describing the world as it is; instead, language is a powerful, often invisible, lens that shapes and constructs the very reality its speakers perceive.

The Information Box

Syllabus Connection:

- Paper 1: Chapter 7 (Linguistic Anthropology), Chapter 1.7 (Language and Culture), Chapter 6 (Anthropological Theories)

Key Concepts/Tags:

- Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis, Linguistic Relativity, Linguistic Determinism, Edward Sapir, Benjamin Lee Whorf, Hopi Time

The Setting: Who, What, Where?

This case study is not about a single place but a powerful idea developed by the American linguist-anthropologist Edward Sapir and his student, Benjamin Lee Whorf. Their work, primarily in the 1920s-1940s, was based on their extensive study of Native American languages, which were structurally very different from European ones. Whorf’s most famous and detailed analysis was of the language of the Hopi people of Arizona. By comparing Hopi grammar to what he called “Standard Average European” languages, he developed the principle of linguistic relativity, now widely known as the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis.

The Core Argument: Why This Study Matters

The hypothesis fundamentally challenged the idea that all humans perceive a single, objective reality. It exists in two main forms:

- The “Strong” Version (Linguistic Determinism): This is the most radical claim. It argues that language determines thought. The grammatical and lexical categories of your language create mental grooves that are so deep, they make it impossible to think certain thoughts. In this view, language is a kind of “prison” for the mind. This version of the hypothesis is now almost universally rejected by anthropologists and linguists.

- The “Weak” Version (Linguistic Relativity): This is the more nuanced and widely accepted version. It argues that language influences thought. Your language doesn’t trap you, but it does “nudge” your perception. It habituates you to pay attention to certain aspects of reality while ignoring others. It’s not a prison, but a familiar room with a specific set of windows onto the world.

- The Classic Example: Hopi Concept of Time: Whorf’s most famous argument was that the Hopi language lacks the words, grammar, and metaphors to treat time as a linear, measurable, and divisible substance (as English does with terms like “wasting time” or “three days“). He argued their language treats time as a cyclical, ongoing process of “becoming later.” From this, he concluded that the Hopi have a fundamentally different, non-linear conception of reality itself.

The Anthropologist’s Gaze: A Critical Perspective

The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis has been one of the most intensely debated ideas in anthropology.

- The Critique of Whorf’s Data: The hypothesis came under fierce attack in the mid-20th century. Later linguists re-examined Whorf’s Hopi research and argued that he had made significant errors. They showed that the Hopi do have a sophisticated system for talking about time and that Whorf, who was not a fluent speaker, may have projected his own philosophical ideas onto their language.

- The “Great Eskimo Vocabulary Hoax”: Similarly, the popular idea that “Eskimos have hundreds of words for snow” (used to support the hypothesis) was largely debunked as an exaggeration. While Yupik and Inuit languages do have several distinct root words for snow, it is not hundreds, and English also has many specific terms (slush, sleet, powder, blizzard). The initial claim was based on poor scholarship.

- The Modern Revival (Neo-Whorfianism): After being largely dismissed, a more nuanced “weak” version of the hypothesis is making a scientific comeback in cognitive science. Modern studies have shown that language can have subtle but measurable effects on perception. For example, speakers of languages that have different words for light blue and dark blue are measurably faster at distinguishing between those two colours, suggesting that language does tune our perception.

The Exam Angle: How to Use This in Your Mains Answer

- Types of Questions Where It Can be Used:

- “What is the relationship between language, thought, and culture?”

- “Critically evaluate the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis.”

- “Discuss the scope and significance of Linguistic Anthropology.”

- Model Integration:

- To define the hypothesis: “The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis proposes that the structure of a language influences its speakers’ worldview. Its ‘weak’ form, linguistic relativity, suggests language shapes thought, as seen in Whorf’s classic (though contested) study of the Hopi concept of time.”

- To distinguish its two forms: “It is crucial to distinguish between linguistic determinism (the ‘strong’ version that language limits thought), which is largely rejected, and linguistic relativity (the ‘weak’ version that language influences thought), which continues to inform modern cognitive science.”

- To offer a critique: “The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis has faced significant criticism. Whorf’s analysis of the Hopi language has been challenged by later linguists, and the famous example of numerous Inuit words for snow was shown to be an exaggeration, highlighting the difficulty of proving a causal link between language and thought.”

Observer’s Take

The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, even in its most contested form, was a revolutionary blow against the assumption of universal human reason. It forced the social sciences to take seriously the idea that speakers of different languages might not just be saying different things, but might actually be living in different cognitive worlds. While we have discarded the simplistic idea that language is a “prison,” the more subtle and profound insight remains: language is the primary toolkit we inherit for constructing our reality. It doesn’t trap us, but it provides the colours, shapes, and textures from which we build our world. Understanding this is to understand the very essence of cultural diversity.