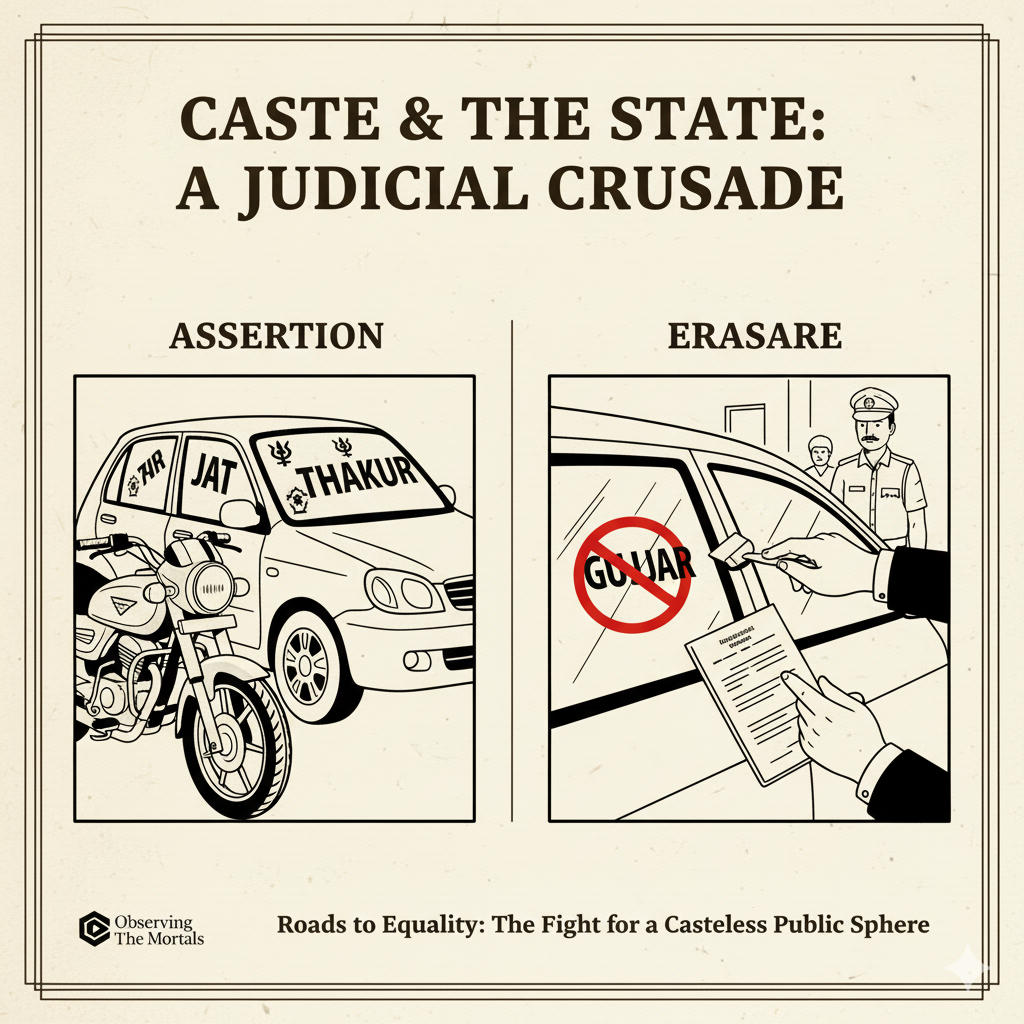

It is a common sight on the roads of North India: a car or a motorcycle proudly displaying the owner’s caste name on its rear windscreen. Is this a harmless expression of identity, or is it a symptom of a deeper social malaise? A landmark order by the Allahabad High Court has forced this question into the national spotlight. In a sweeping directive, the court has moved beyond a routine criminal case to confront the “complex realities” and “toxic masculinity” of everyday caste assertion in modern India, ordering the state to remove caste from police records and public view. This case study explores a powerful judicial intervention that challenges the very visibility of caste in public life.

The Information Box

Syllabus Connection:

- Paper 2: Chapter 3 (Caste System: Features, Contemporary changes, Casteism), Chapter 8 (Social Change)

- Paper 1: Chapter 4.3 (Legal Anthropology), Chapter 2.5 (Social Control), Chapter 4 (Political Anthropology)

Key Concepts/Tags:

- Casteism, Legal Anthropology, Social Justice, State and Caste, Symbolic Assertion, Allahabad High Court

The Setting: Who, What, Where?

This case study is centered on a series of significant directives issued by the Allahabad High Court in Uttar Pradesh. Originating from a routine case, the court took serious note of the police practice of mentioning the caste of all parties in an FIR. This led to a broader set of orders aimed at the UP Police and the state’s Home Department, targeting not just bureaucratic procedures but also the widespread social phenomenon of publicly displaying caste identity on vehicles and social media platforms.

The Core Argument: Why This Study Matters

This is not just a legal ruling; it is a profound sociological and anthropological statement on the nature of caste in the 21st century.

- Challenging the “Caste-Blind” Bureaucracy: The core of the case was the clash between the police’s justification of mentioning caste as a neutral “scientific method of investigation” and the court’s powerful rebuttal. The court slammed this as an “ivory-tower” perspective, forcing the state to acknowledge that mentioning caste is never a neutral act. In a society structured by caste, the act of officially naming it in an FIR can trigger prejudice and bias from the very start of the legal process.

- Caste as a “Performative” Identity: The court’s observations are deeply anthropological. It astutely identified the modern trend of “performative” caste identity, especially among youth on digital platforms like Instagram and YouTube. Caste is no longer just a background identity; it is something to be actively performed, displayed, and celebrated, often to assert social dominance.

- Linking Caste to “Toxic Digi-Masculinity”: In a remarkably sharp analysis, the court connected this performative pride to a regressive, rural honor code and a form of “toxic digi-masculinity.” It argued that caste stickers on vehicles and aggressive social media posts are not just about identity; they are about asserting a hyper-masculine, often historically-rooted, feudal dominance in the public sphere.

The Anthropologist’s Gaze: A Critical Perspective

- The Limits of Legal Fiat: An anthropologist would ask: Can casteism be truly erased by removing the word “caste” from a document or a sticker from a car? While this is a crucial step in tackling the symbols of casteism, it doesn’t address the underlying structural inequalities in land, wealth, and opportunity that give caste its power. There is a risk of it becoming a cosmetic change if not backed by deeper socio-economic reforms.

- The “Necessary Exception” Paradox: The order’s necessary exception for cases under the SC/ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act highlights the central paradox of caste policy in India. To fight caste-based atrocities, the state must recognize and name the caste of the victim and perpetrator. This reveals the tension between the ultimate ideal of a “casteless society” and the immediate reality of needing caste-based laws for protection and affirmative action.

- Dominant vs. Subaltern Assertion: The court’s observations rightly focus on the “romanticised caste aggression” of dominant groups. An anthropologist would add the perspective of Dalit and other marginalized communities, for whom the public assertion of their caste identity (e.g., through symbols of Ambedkar or the word “Dalit”) is often an act of political resistance and counter-hegemonic pride, not aggression. A potential challenge for the state will be to distinguish between these two very different forms of caste assertion.

The Exam Angle: How to Use This in Your Mains Answer

- Types of Questions Where It Can be Used:

- “Casteism in contemporary India manifests in both old and new forms. Discuss.”

- “Analyze the role of the judiciary as an instrument of social reform in India.”

- GS-1/2: “Discuss the impact of digitalization on Indian social structures.”

- Model Integration:

- On Casteism: “Contemporary casteism is not only about discrimination but also about the symbolic assertion of dominance. The Allahabad High Court recently took note of this ‘performative’ caste pride on vehicles and social media, linking it to a ‘toxic digi-masculinity’ and ordering the removal of caste from police records to curb this prejudice at an institutional level.”

- On the Judiciary (GS-2): “The judiciary in India often plays a proactive role in social reform. The Allahabad High Court’s recent directive to the UP government to ban caste stickers on vehicles and remove caste from FIRs is a powerful example of judicial intervention aimed at dismantling the everyday symbols that perpetuate caste prejudice.”

- On Social Change: “The impact of digitalization on social structures is profound. The Allahabad High Court observed how platforms like YouTube and Instagram have become stages for a ‘performative’ and often aggressive assertion of caste identity among youth, prompting it to order stricter regulations to counter this trend.”

Observer’s Take

The Allahabad High Court’s order is a remarkable and courageous intervention. It moves beyond dry legal technicalities to perform a sharp anthropological diagnosis of a deep social sickness. The court astutely recognizes that caste in the 21st century is not a dying relic; it is a dynamic, performative, and often toxic force, amplified and given new life by modern technology. While erasing a word from a form or a sticker from a car cannot instantly erase prejudice from the heart, it is a crucial and symbolic first step. It is an act of the state refusing to be a passive registrar of social inequality and, instead, taking an active stand to dismantle the everyday symbols that give prejudice its power and public visibility