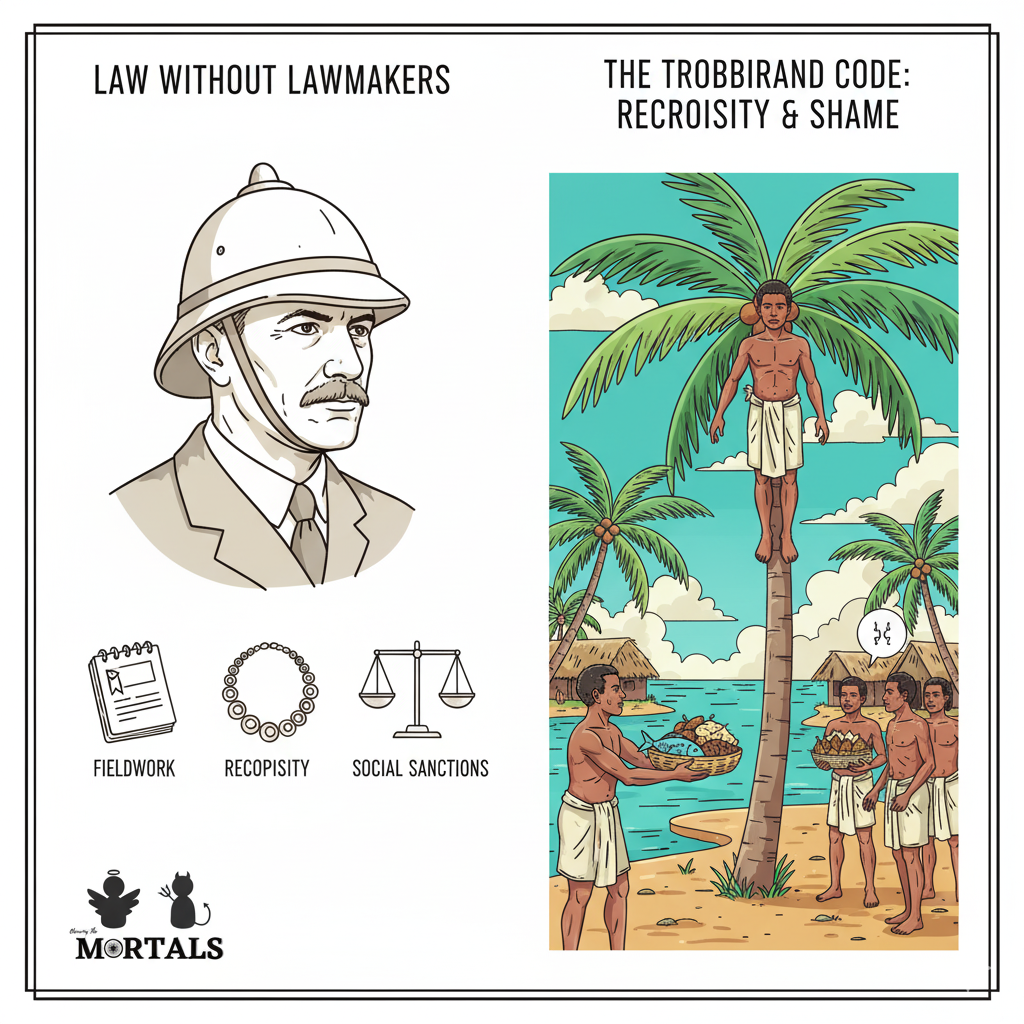

What is “law”? Do you need a formal government, written statutes, and a police force for law to exist? For much of Western history, the answer was a resounding “yes.” So-called “primitive” societies were seen as being ruled by a rigid, unthinking “cake of custom,” not by rational law. Then, in the early 20th century, the pioneering anthropologist Bronisław Malinowski, stranded on a remote Pacific island, observed a system that would turn this ethnocentric view on its head. This case study explores his discovery of a complex and effective legal system that was woven into the very fabric of everyday life.

The Information Box

Syllabus Connection:

- Paper 1: Chapter 4.3 (Legal Anthropology), Chapter 4.1 (Political Anthropology: Stateless Societies), Chapter 1.8 (Fieldwork Traditions in Anthropology)

Key Concepts/Tags:

- Bronisław Malinowski, Trobriand Islanders, Legal Anthropology, Reciprocity, Social Control, Crime and Custom

The Setting: Who, What, Where?

This is the world of Bronisław Malinowski, the Polish-British anthropologist credited with developing the intensive, long-term participant-observation method of fieldwork. His groundbreaking insights come from his 1926 monograph, Crime and Custom in Savage Society. The analysis is based on his immersive fieldwork among the Trobriand Islanders, a community living on a group of coral atolls off the eastern coast of New Guinea. Malinowski was famously stranded there during World War I, allowing him to conduct unprecedentedly deep and long-term research.

The Core Argument: Why This Study Matters

Malinowski’s work was a direct assault on the prevailing colonial-era theories about “primitive” law. He made three revolutionary arguments:

- Demolishing the “Cake of Custom” Myth: Malinowski attacked the then-popular idea that people in “savage” societies followed their rules blindly, automatically, and without question, like mindless ants. Through detailed observation, he showed this was false. The Trobriand Islanders were rational, self-interested individuals who were constantly tempted to shirk their duties, evade their obligations, and find loopholes in the system, just like people in any other society.

- Discovering “Civil Law” Based on Reciprocity: If they weren’t blindly obedient, what kept their society from falling apart? Malinowski argued that the Trobrianders had a robust system of what he called “civil law,” and its engine was the principle of reciprocity. Social order was maintained because every person was bound in a complex web of mutual, interlocking obligations. A fisherman in a coastal village was obligated to give fish to his partner in an inland village, who was in turn obligated to provide him with yams. If the fisherman stopped giving fish, the supply of yams would stop. The system was largely self-enforcing through enlightened self-interest, not through fear of a chief’s punishment.

- The Power of Social Sanctions: For more serious offenses—what we might call “criminal law”—against sacred rules like the taboo on clan incest, the enforcement mechanism was different. It wasn’t a formal punishment from a court, but the threat and application of public shame and ridicule. Malinowski provided the powerful ethnographic example of a young man who was discovered to be having an affair with his maternal cousin (a strict taboo). Though many knew quietly, he was publicly insulted by a rival. The social shame was so unbearable that the young man followed tradition, climbed to the top of a palm tree, delivered a farewell speech, and leaped to his death—the customary way for a wronged Trobriander to show the gravity of the injustice they had suffered. This demonstrated how powerful social sanctions, not a formal state, enforced their most important laws.

The Anthropologist’s Gaze: A Critical Perspective

- Over-emphasizing Harmony?: Malinowski’s functionalist approach, which focused on how reciprocity maintained social equilibrium, has been criticized for potentially downplaying the real roles of conflict, power imbalances, and coercion within Trobriand society.

- Defining “Law” Too Broadly?: Some later legal anthropologists have argued that Malinowski’s definition of “law” was too expansive. By equating it with the bonds of reciprocity that govern all social life, did he blur the important distinction between general social norms and actual “law,” which is usually defined by the presence of a specific authority that has the right to apply sanctions?

- The “Ethnographic Present”: Like many of his contemporaries, Malinowski often wrote in the “ethnographic present,” which can give a timeless and static picture of a society. This style can sometimes obscure the historical changes and the ongoing impact of colonialism that were already affecting the Trobriand Islands during his fieldwork.

The Exam Angle: How to Use This in Your Mains Answer

- Types of Questions Where It can be Used:

- “What is law? Discuss the nature of law and social control in simple societies.”

- “Critically evaluate the key contributions of Bronisław Malinowski to social anthropology.”

- “Distinguish between formal and informal mechanisms of social control with ethnographic examples.”

- Model Integration:

- On Legal Anthropology: “Bronisław Malinowski’s study of the Trobriand Islanders revolutionized legal anthropology. In ‘Crime and Custom in Savage Society,’ he demonstrated that law could exist without a state, arguing that their ‘civil law’ was based not on formal commands but on the binding, self-enforcing force of reciprocity.”

- On Social Control: “In stateless societies, informal sanctions like shame are often more powerful than formal punishments. Malinowski’s classic example is of a Trobriand man who committed ritual suicide after being publicly shamed for incest, demonstrating how the immense power of social pressure enforces the most sacred rules.”

- On Malinowski’s Contribution: “Beyond the Kula Ring, Malinowski’s great contribution was demolishing the myth of the ‘savage’ who blindly follows custom. He showed that the Trobrianders were rational actors who navigated a complex system of mutual obligations, thus establishing the foundation for the modern anthropological study of law.”

Observer’s Take

Malinowski’s work did more than just document the life of a distant people; it forced Western society to confront its own ethnocentric arrogance. He proved that “law and order” are not the exclusive inventions of “civilized” states with their courts, police, and prisons. He uncovered a sophisticated and highly effective legal system that was woven into the very fabric of daily economic and social life. The study of the Trobriand Islanders is an enduring lesson that to find law, we must often look beyond formal institutions and into the intricate web of relationships, obligations, and moral sentiments that bind any human community together.