For over seventy years, “development” has been the grand project of our time—a self-evident goal for nations in the “Third World” to escape poverty and catch up with the “First World.” We see it as a natural, desirable process of progress. But what if the entire idea of “development” was a carefully constructed fiction? This was the explosive argument of the Colombian-American anthropologist Arturo Escobar. He argued that “development” was a powerful discourse invented by the West after World War II to create a new, more subtle form of global power. This case study explores his influential and deeply unsettling critique.

The Information Box

Syllabus Connection:

- Paper 1: Chapter 10 (Development Anthropology), Chapter 9 (Applied Anthropology), Chapter 6 (Anthropological Theories: Post-structuralism)

Key Concepts/Tags:

- Arturo Escobar, Development as Discourse, Post-Development, Foucault, The Invention of Poverty, Third World

The Setting: Who, What, Where?

This is a landmark theory from the field of post-development studies, pioneered by Arturo Escobar. His analysis is most famously laid out in his 1995 book, Encountering Development: The Making and Unmaking of the Third World. Using a theoretical lens heavily influenced by the work of Michel Foucault, Escobar was not studying a single village project but the entire global “development industry”—the vast apparatus of the World Bank, the IMF, United Nations agencies, and national development programs that emerged in the aftermath of World War II.

The Core Argument: Why This Study Matters

Escobar’s work is a fundamental critique of the entire development paradigm. He argued that to understand development, we must see it not as a set of actions, but as a system of knowledge and power.

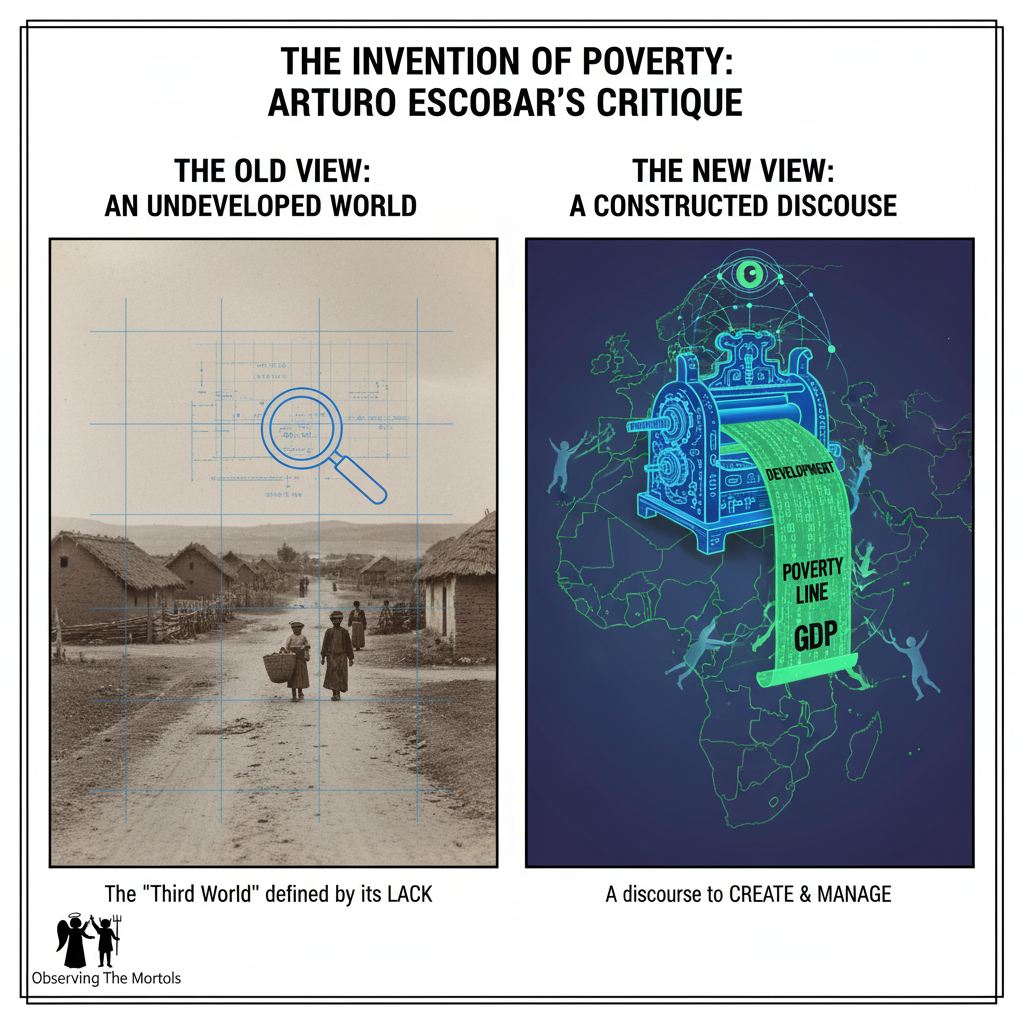

- “Development” as a Discourse of Power: This is the central thesis. Escobar argued that “development” is a discourse—a powerful way of thinking, talking, and producing knowledge about the world that creates the very reality it claims to describe. This discourse, he claims, was effectively launched by U.S. President Harry Truman in his 1949 inaugural address, where he defined the majority of the world as “underdeveloped areas.”

- The “Invention” of the Third World and Poverty: Before 1949, communities in Asia, Africa, and Latin America may have been poor, but they were not “underdeveloped.” The discourse of development created the abstract category of the “Third World” and defined these diverse societies by what they lacked in comparison to the West (e.g., low GDP, lack of dams, few factories). It “invented poverty” as a scientifically measurable problem (e.g., living on less than $2 a day) that could then be “solved” by the intervention of Western experts, technology, and capital.

- A New Machinery of Control: This discourse gave birth to a vast institutional machinery (the World Bank, aid agencies, NGOs, university development programs) to study and “manage” this new problem of underdevelopment. Escobar argued this was a new, more effective form of colonialism. Instead of direct political rule, the West now managed and controlled the post-colonial world by defining its problems and selling the solutions, ensuring these nations remained integrated into the global capitalist system on Western terms.

The Anthropologist’s Gaze: A Critical Perspective

Escobar’s powerful critique has been hugely influential, but it has also faced its own critical scrutiny.

- Is it Overly Pessimistic?: Critics argue that while the development industry has major flaws and a neocolonial legacy, Escobar’s all-encompassing critique can be overly pessimistic. Does it deny the real, tangible benefits that some development projects—like vaccination campaigns, sanitation improvements, or agricultural innovations—have brought to millions of people? Does it dismiss the agency of people in the Global South who genuinely desire forms of material improvement?

- Romanticizing the “Local”?: The post-development school, which Escobar is a part of, often champions “alternatives to development” based on local, grassroots, and indigenous knowledge. A critical perspective would question whether this approach sometimes romanticizes the “local” and overlooks the internal power structures, inequalities (like patriarchy or caste), and hardships that can exist within these traditional communities.

- A Lack of Concrete Alternatives?: While Escobar provides a brilliant and powerful deconstruction of the development myth, a common criticism is that post-development theory is sometimes less successful at offering concrete, scalable alternatives to address the massive global problems of poverty and inequality.

The Exam Angle: How to Use This in Your Mains Answer

- Types of Questions Where It can be Used:

- “Critically analyze the anthropological approaches to the study of development.”

- “The concept of ‘development’ is a social construct with a specific political history. Discuss.”

- GS/Essay: On topics of globalization, international aid, and the failures of top-down development models.

- Model Integration:

- On Development Anthropology: “A major contribution of post-development theorists like Arturo Escobar is the critique of ‘development’ itself as a discourse of power. In his work ‘Encountering Development,’ he argued that the very concept of the ‘Third World’ was an invention of the post-WWII era, a way for the West to manage and control post-colonial nations through a new machinery of aid and expertise.”

- To offer a critical view on development: “Beyond analyzing the impacts of specific projects, a critical anthropological perspective questions the development paradigm itself. Arturo Escobar, for example, argued that development ‘invented poverty’ as a measurable problem, which then justified Western intervention and often led to the disempowerment of local communities and their knowledge systems.”

- For a GS/Essay Answer: “The failure of many top-down international aid programs can be understood through the lens of post-development theory. Thinkers like Arturo Escobar argue that ‘development’ often fails because it imposes a singular, Western model of progress and ignores local knowledge, treating people as statistical problems to be solved rather than as agents of their own change.”

Observer’s Take

Arturo Escobar’s work is like an intellectual bomb thrown into the comfortable, common-sense world of “development.” He forces us to ask a deeply uncomfortable question: what if the entire seventy-year-long project of “helping” the “underdeveloped” world was, from its very beginning, a sophisticated new chapter in the history of global power? His theory is a crucial antidote to the naive belief that development is a simple, neutral act of charity. It serves as a powerful reminder to be deeply skeptical of grand, top-down plans, to listen to and value local and indigenous alternatives, and to recognize that sometimes the most powerful act is not to offer a new solution, but to fundamentally question the very definition of the problem.