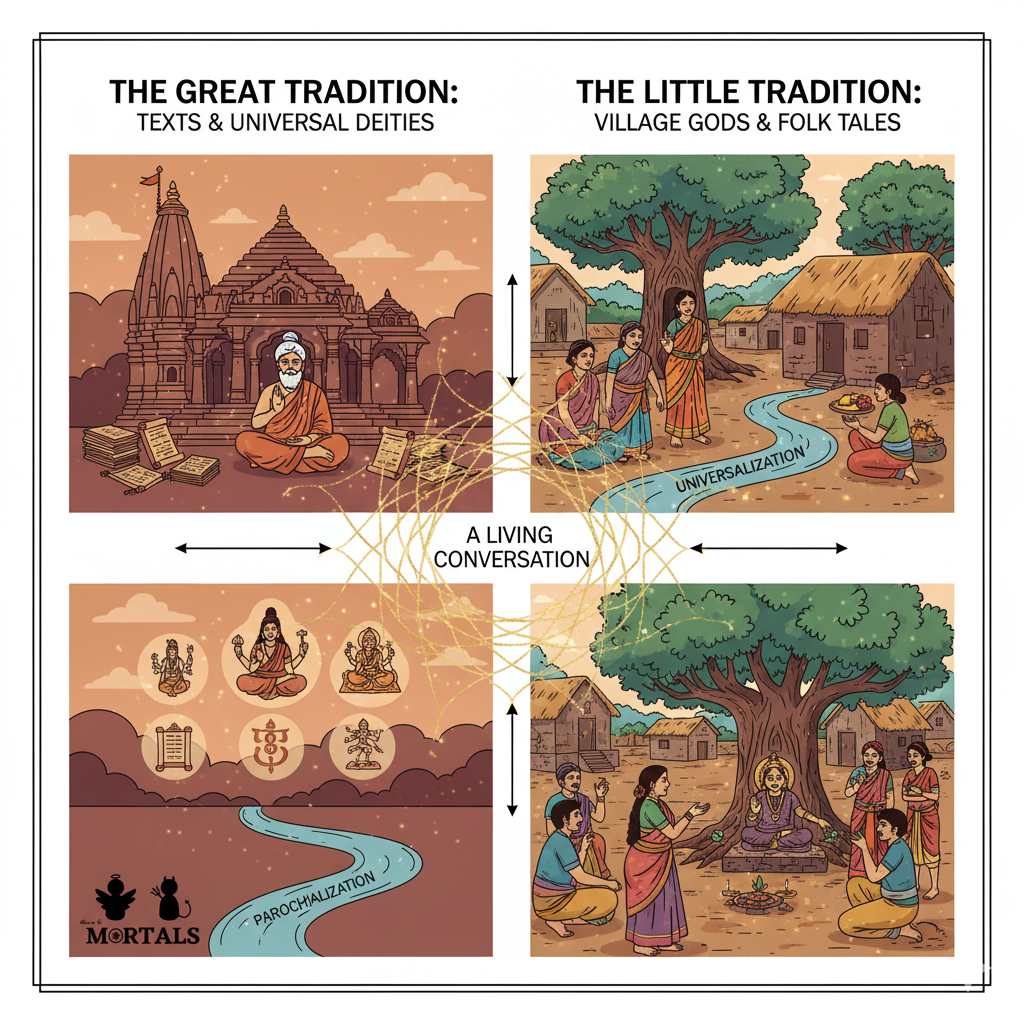

How can a single civilization contain thousands of unique village deities, local customs, and folk tales, while simultaneously sharing a common set of gods, festivals, and sacred texts known across the subcontinent? This paradox of unity in diversity has long fascinated observers of India. In the mid-20th century, a group of anthropologists proposed a powerful model to understand this. They introduced the concepts of “Great Tradition” and “Little Tradition,” arguing that Indian culture is a product of a constant, two-way dialogue between the world of the learned, pan-Indian elite and the world of the local, village-based folk.

The Information Box

Syllabus Connection:

- Paper 2: Chapter 1.1 (Indian Civilization), Chapter 4 (Religion and Society)

- Paper 1: Chapter 6 (Anthropological Theories), Chapter 2.1 (Culture)

Key Concepts/Tags:

- Great Tradition, Little Tradition, Universalization, Parochialization, Robert Redfield, McKim Marriott, Indian Civilization

The Setting: Who, What, Where?

The concepts of Great and Little Traditions were originally developed by the American anthropologist Robert Redfield based on his research in Mexico. However, they found their most famous and influential application in the Indian context through the work of anthropologists like McKim Marriott (in his study of Kishangarhi village in Uttar Pradesh) and Milton Singer. They were part of a wave of scholars in the 1950s trying to create an anthropological framework to understand a complex, ancient civilization like India, moving beyond the traditional focus on isolated, “primitive” tribes.

The Core Argument: Why This Study Matters

This model provided a dynamic way to understand the structure and functioning of Hindu civilization, seeing it as an interconnected web rather than a collection of separate parts.

- Defining the Two Traditions:

- The Great Tradition is the formal, literate, and reflective tradition of the religious and cultural elite. It is found in classical Sanskrit texts (like the Vedas, Upanishads, and Puranas), is generally pan-Indian in its scope, and is consciously cultivated and transmitted by priests, scholars, and philosophers in temples, schools, and urban centers.

- The Little Tradition is the informal, largely unwritten, and oral tradition of the common people in the villages. It is local, diverse, and often spontaneous. It includes the worship of village deities (gram devatas), spirits, ancestors, and local heroes, and is transmitted through folk songs, stories, and festivals.

- The Two-Way Street of Culture: The most brilliant insight of the model is that these two traditions are not separate and sealed off from each other. They are in a state of constant, dynamic interaction. McKim Marriott famously coined two terms to describe this two-way flow:

- Universalization: This is the process by which an element of a Little Tradition (like a local village goddess, a folk belief, or a hero) moves “upward” and becomes identified with, or absorbed into, the Great Tradition. For example, a local mother goddess might be reinterpreted and worshipped as a form of the pan-Indian deity Lakshmi or Parvati, gaining wider recognition and scriptural sanction.

- Parochialization: This is the opposite process, where an element of the Great Tradition (a deity, a festival, a story from an epic) moves “downward” and is adapted, modified, and integrated into the local context of the Little Tradition. For example, a national Sanskritic festival like Navaratri or Diwali is celebrated with unique local customs, stories, and meanings that are specific to that village or region.

- A Web of Civilization: This continuous, two-way conversation between the “great” and the “little” creates a vast, interconnected cultural and religious web. It is this web that allows for immense local diversity while simultaneously maintaining a shared civilizational framework that unifies the subcontinent.

The Anthropologist’s Gaze: A Critical Perspective

While highly influential, the Great/Little Tradition model has faced significant criticism.

- An Oversimplified Dichotomy?: Critics argue that the binary division into just “Great” and “Little” is a major oversimplification. In reality, Indian tradition is multi-layered, with many intermediate levels—regional traditions, sub-regional traditions, caste-specific traditions, etc.—that this simple dichotomy fails to capture.

- An Implicit Hierarchy: Despite the emphasis on a “two-way street,” the very terms “Great” (implying sophisticated, important) and “Little” (implying rustic, simple) contain an implicit value judgment and hierarchy. The model can be seen as privileging the textual, Sanskritic tradition as the ultimate source of cultural legitimacy.

- Ignoring Conflict and Power: The model presents a very harmonious, organic, and consensual process of cultural flow. It tends to ignore the role of power, conflict, and resistance. Was the absorption of a local deity into the Hindu pantheon always a peaceful process of “universalization,” or was it sometimes a form of cultural appropriation and conquest by the dominant Brahmanical tradition, aimed at erasing a local identity?

The Exam Angle: How to Use This in Your Mains Answer

- Types of Questions Where It can be Used:

- “Critically analyze the conceptual models for understanding the unity and diversity of Indian civilization.”

- “What is the relationship between folk and classical traditions in India?”

- “Discuss the processes of social and cultural change in rural India.”

- Model Integration:

- To define the concept: “The complexity of Indian civilization can be understood through the model of Great and Little Traditions. This framework, applied to India by anthropologists like McKim Marriott, describes the continuous interaction between the pan-Indian, textual ‘Great Tradition’ and the diverse, local ‘Little Traditions’ of the villages.”

- To explain the dynamics: “The key insight of this model is the two-way process of cultural flow. ‘Universalization’ describes a folk element moving upward into the Great Tradition, while ‘Parochialization’ describes a great tradition element being localized, as McKim Marriott demonstrated in his study of Kishangarhi village.”

- To offer a critique: “While the Great and Little Tradition model is useful for understanding cultural interaction, it has been critiqued for its simplistic dichotomy and for under-emphasizing the role of power. The process of ‘universalization,’ for instance, can also be seen as a form of cultural co-option by the dominant Sanskritic tradition rather than a purely organic dialogue.”

Observer’s Take

The Great and Little Traditions model was a revolutionary step in the anthropology of India. It offered a way to see the civilization not as a static collection of ancient texts or a chaotic jumble of village customs, but as a living, breathing organism in a constant state of conversation with itself. While the model has its critics, its core insight remains powerful: the strength and resilience of Indian culture lie in this very dialogue. It is the ability of the grand, epic narratives to take root in local soil, and for the local soil to, in turn, send up new shoots that can grow to become part of the great civilizational tree, that defines this unique and enduring culture.