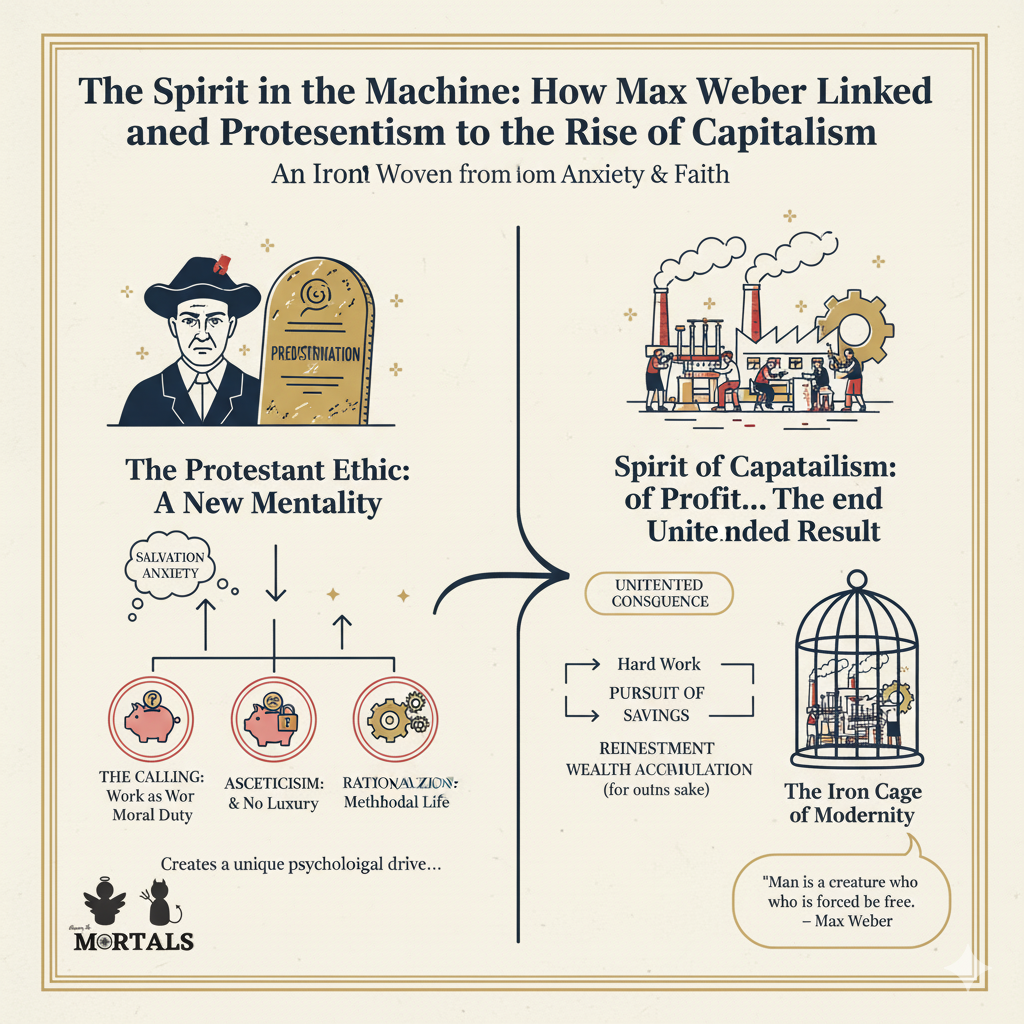

Where did the modern capitalist mindset come from? Is the restless, rational, and relentless pursuit of profit simply human nature unleashed? The German sociologist and political economist Max Weber, one of the founders of modern social science, offered a startlingly different answer. In one of the most famous essays ever written, he argued that the unique “spirit” of modern capitalism had its unexpected origins in the intense spiritual anxiety of a specific group of Protestant reformers in the 16th and 17th centuries. This case study explores his profound and deeply influential thesis on the hidden connections between faith and finance.

The Information Box

Syllabus Connection:

- Paper 1: Chapter 5 (Anthropology of Religion), Chapter 3 (Economic Anthropology), Chapter 6 (Anthropological Theories)

- Paper 2: Chapter 4 (Religion and Society in India – provides a comparative framework)

Key Concepts/Tags:

- Max Weber, Protestant Ethic, Spirit of Capitalism, Predestination, The Calling, Rationalization

The Setting: Who, What, Where?

This is the intellectual world of Max Weber (1864-1920), a towering figure in sociology and a major influence on anthropology. His argument is laid out in his 1905 work, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. This is not an ethnography but a work of historical sociology. Weber was trying to understand a specific historical puzzle: why did modern, rational, industrial capitalism emerge first and most powerfully in the Protestant nations of Western Europe and North America?

The Core Argument: Why This Study Matters

Weber’s work was a direct challenge to purely materialist explanations of economic change (like Marxism). He argued that a specific set of religious ideas created a unique psychological motivation that became the engine for capitalism.

- Defining the “Spirit of Capitalism”: Weber was not talking about simple greed, which has always existed. He was talking about a new, peculiar mindset: the belief that it is a moral and ethical duty to work diligently in one’s worldly profession (a “calling”), to be frugal and avoid luxury, and to systematically reinvest profits to accumulate more, not for personal enjoyment, but as an end in itself. It is a rational, methodical, and deeply ascetic pursuit of wealth.

- Finding the Engine: The “Protestant Ethic”: Weber traced the origin of this spirit to the doctrines of certain Protestant sects, particularly Calvinism. The key psychological driver was the terrifying doctrine of Predestination.

- The Doctrine: Calvinists believed that God, from the beginning of time, had already chosen who was saved (the “elect”) and who was damned. Nothing an individual did in their life could change this unalterable fate.

- The Psychological Crisis: This belief created an unbearable feeling of “salvation anxiety.” Believers were desperate for some sign or clue that they were among the saved.

- The “Solution”: Protestant pastors suggested that while good works couldn’t earn salvation, relentless, methodical, and successful work in one’s worldly “calling” could be interpreted as a sign that one was indeed chosen by God.

- The Unintended Consequence: This created a generation of intensely motivated individuals who worked tirelessly, lived frugally (as spending on luxury was a sin), and reinvested their profits. They accumulated vast amounts of capital not because they wanted to be rich in a worldly sense, but as a byproduct of their religious anxiety. This psychological state, Weber argued, was the unintended and ironic engine that created the “spirit of modern capitalism.”

The Anthropologist’s Gaze: A Critical Perspective

- Correlation vs. Causation: The most significant and enduring critique is whether Weber truly proved a causal link. Did the Protestant Ethic cause capitalism, or did it merely have an “elective affinity” with an economic system that was already emerging due to other material factors (like technology, colonialism, and legal changes)?

- A Misreading of Theology?: Some historians and theologians have argued that Weber oversimplified or misinterpreted complex Protestant doctrines like “the calling” to better fit his grand thesis.

- The Problem of Ethnocentrism: Weber’s work on the Protestant Ethic was part of a larger project where he also studied the religions of India and China to understand why capitalism did not emerge there in the same way. This later work has been heavily criticized for being Eurocentric. By framing the question as what these societies “lacked,” he used a Western model as the universal benchmark for progress, often leading to a distorted and simplistic understanding of complex non-Western economic and religious histories.

The Exam Angle: How to Use This in Your Mains Answer

- Types of Questions Where It can be Used:

- “Critically evaluate the relationship between religion and economy with anthropological examples.”

- “Discuss the key contributions of Max Weber to social and anthropological thought.”

- As a counter-argument in questions on Marxist or Cultural Materialist theories.

- Model Integration:

- On Religion and Economy: “The profound link between religious ideology and economic systems was famously analyzed by Max Weber in ‘The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism.’ He argued that the rise of modern capitalism in the West was psychologically fueled by the Calvinist doctrines of predestination and the worldly ‘calling’.”

- To show theoretical contrast: “In direct contrast to purely materialist theories, Max Weber provided a classic idealist explanation for economic change. His Protestant Ethic thesis argued that a specific set of religious ideas (superstructure) was a crucial causal factor in the emergence of a new economic system (base).”

- For a comparative/critical view (Paper 2): “While Max Weber’s work on the Protestant Ethic is foundational, his subsequent attempts to explain why capitalism did not arise in India have been heavily critiqued for being Eurocentric. He is often accused of downplaying the dynamism of the pre-colonial Indian economy and misinterpreting Hindu doctrines to fit his preconceived model.”

Observer’s Take

Max Weber’s thesis is one of the most audacious and intellectually thrilling arguments in the social sciences. It’s a grand detective story that traces the origins of our modern, hyper-rational economic world back to the anxious souls of 16th-century religious reformers. Whether he was entirely right is a debate that still rages, but his genius was to show that the “spirit” of an economic system—its values, its ethics, its psychological fuel—can have deep and unexpected roots in the most sacred corners of a culture. His work is a powerful and enduring reminder that to understand how people behave with their money, you must first understand what they believe about their souls.