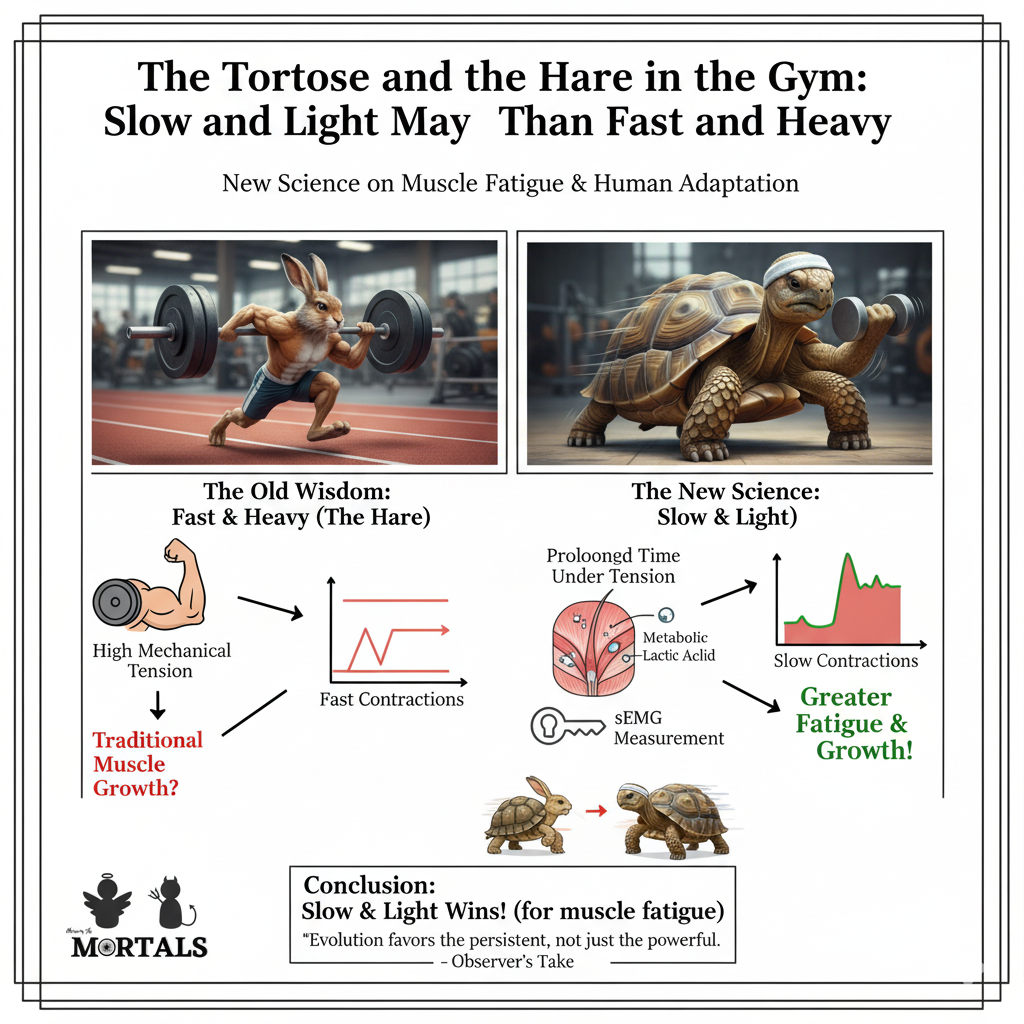

For decades, the gospel of the gym has been simple: to build muscle, you must lift heavy weights. The philosophy has been one of brute force—more weight, more power, more growth. But what if there’s another, more subtle, and perhaps even more effective path to strength? A fascinating new study published in the Journal of Physiological Anthropology puts this old wisdom to the test. Using advanced technology to peer “under the hood” of our muscles, scientists have found that a counter-intuitive method—lifting lighter weights very slowly—can induce even more fatigue than traditional heavy lifting. This case study explores the science that could revolutionize how we think about strength, safety, and human adaptation.

The Information Box

Syllabus Connection:

- Paper 1: Chapter 1.3 (Scope of Physical/Biological Anthropology), Chapter 11.2 (Human Growth and Development), Chapter 9 (Human Genetics and adaptation)

Key Concepts/Tags:

- Physiological Anthropology, LST (Low-intensity Slow Training), Muscle Fatigue, sEMG, Human Adaptation, Exercise Physiology

The Setting: Who, What, Where?

The setting is a modern exercise physiology laboratory, with the research published in the Journal of Physiological Anthropology by a team of Japanese scientists. The study involved 23 healthy male students performing leg extension exercises. The researchers compared two distinct methods:

- TRAD (Traditional): Lifting a heavy weight (80% of maximum) with fast, 1-second movements.

- LST (Low-intensity Slow Training): Lifting a much lighter weight (50% of maximum) with very slow, controlled movements (a 7-second repetition). The key technology used was Surface Electromyography (sEMG), a non-invasive method of placing electrodes on the skin to measure the electrical activity and fatigue levels within a muscle.

The Core Argument: Why This Study Matters

This scientific study provides a powerful neuromuscular explanation for the effectiveness of a safer and more accessible training method.

- The Counter-Intuitive Finding: The study’s most significant conclusion was that performing three sets of the slow, low-weight (LST) exercise induced more measurable muscle fatigue than both one set of LST and, surprisingly, even three sets of the traditional, heavy-weight (TRAD) exercise.

- The Power of “Metabolic Stress”: The researchers speculate that the key is the prolonged time the muscle is under tension during the slow LST repetitions. This sustained contraction restricts blood flow and oxygen to the muscle, leading to a much greater accumulation of metabolic byproducts (like lactic acid, which causes the “burn”). This state, known as “metabolic stress,” is now understood to be a primary trigger for the body’s adaptive response to build more muscle.

- Redefining the Path to Strength: The findings provide a strong scientific basis for why LST is so effective. It proves that muscle growth is not just about the mechanical tension from lifting a heavy weight; the metabolic stress from sustained, controlled contractions is an equally, if not more, important factor. This has huge implications, as it makes effective strength training far more accessible and safer for people who cannot or should not lift heavy loads, such as the elderly, people recovering from injury, or those new to exercise.

The Anthropologist’s Gaze: A Critical Perspective

- Human Plasticity in Action: A physical anthropologist would see this study as a beautiful, micro-level example of human plasticity—our body’s remarkable ability to adapt to a wide range of environmental stimuli. The study elegantly shows how different types of physical stress (heavy and fast vs. light and slow) trigger different but equally potent physiological responses, both of which can lead to the long-term adaptation of muscle growth.

- The Scientific Face of Anthropology: This case study is a perfect example of the scientific, experimental, and quantitative side of physical anthropology. It moves beyond observation and interpretation to use hypothesis testing, controlled variables, and advanced measurement technology (sEMG) to produce objective data about human biological function. It’s a great counterpoint to the qualitative methods of social anthropology.

- The Cultural Context of “Fitness”: While the study itself is purely physiological, a broader anthropological gaze would place it in its cultural context. The very concept of structured “resistance training” for the specific goal of “muscle hypertrophy” is a modern cultural phenomenon, tied to societal ideals of health, aesthetics, youthfulness, and performance. This research is part of a larger cultural project to rationalize, optimize, and gain scientific control over the human body.

The Exam Angle: How to Use This in Your Mains Answer

- Types of Questions Where It can be Used:

- “Discuss the scope and methods of Physical Anthropology.”

- “Explain the concept of human adaptation to various environmental and bio-cultural stresses.”

- “What are the anthropological perspectives on ageing?” (as LST is a safer alternative for the elderly).

- Model Integration:

- On the Scope of Physical Anthropology: “The scope of modern physical anthropology includes the scientific study of human physiological adaptation. For example, recent studies in the ‘Journal of Physiological Anthropology’ use technologies like sEMG to experimentally compare how different exercise methods, like Low-intensity Slow Training, induce muscle fatigue and trigger adaptive responses like hypertrophy.”

- On Human Adaptation: “Human plasticity allows our bodies to adapt to a wide range of physical stressors. Research into exercise methods like Low-intensity Slow Training (LST) demonstrates that prolonged muscle tension can create significant metabolic stress, which is a key stimulus for muscle growth. This shows an alternative adaptive pathway to that of traditional high-intensity, high-load training.”

- For GS-3 (Science & Tech): “Innovations in sports and health science are leading to safer and more effective training methods. For instance, research on Low-intensity Slow Training (LST) has scientifically shown that slow movements with lighter weights can induce significant muscle fatigue, making it a viable and safer alternative to heavy lifting, especially for aging populations or for rehabilitation.”

Observer’s Take

This study is a fascinating glimpse into the intricate conversation between our muscles and our brains. It reminds us that in the quest for physical strength and adaptation, brute force is not the only answer. The quiet, sustained, and deliberate stress of slow, controlled movement can be just as, if not more, potent. This is not just a lesson for the gym; it’s an elegant metaphor for growth and adaptation itself. It reveals that our bodies are incredibly intelligent systems, responding not just to the sheer weight we lift, but to the time, tension, and intention we apply. It’s a powerful piece of science that gives new meaning to the old fable of the tortoise and the hare.