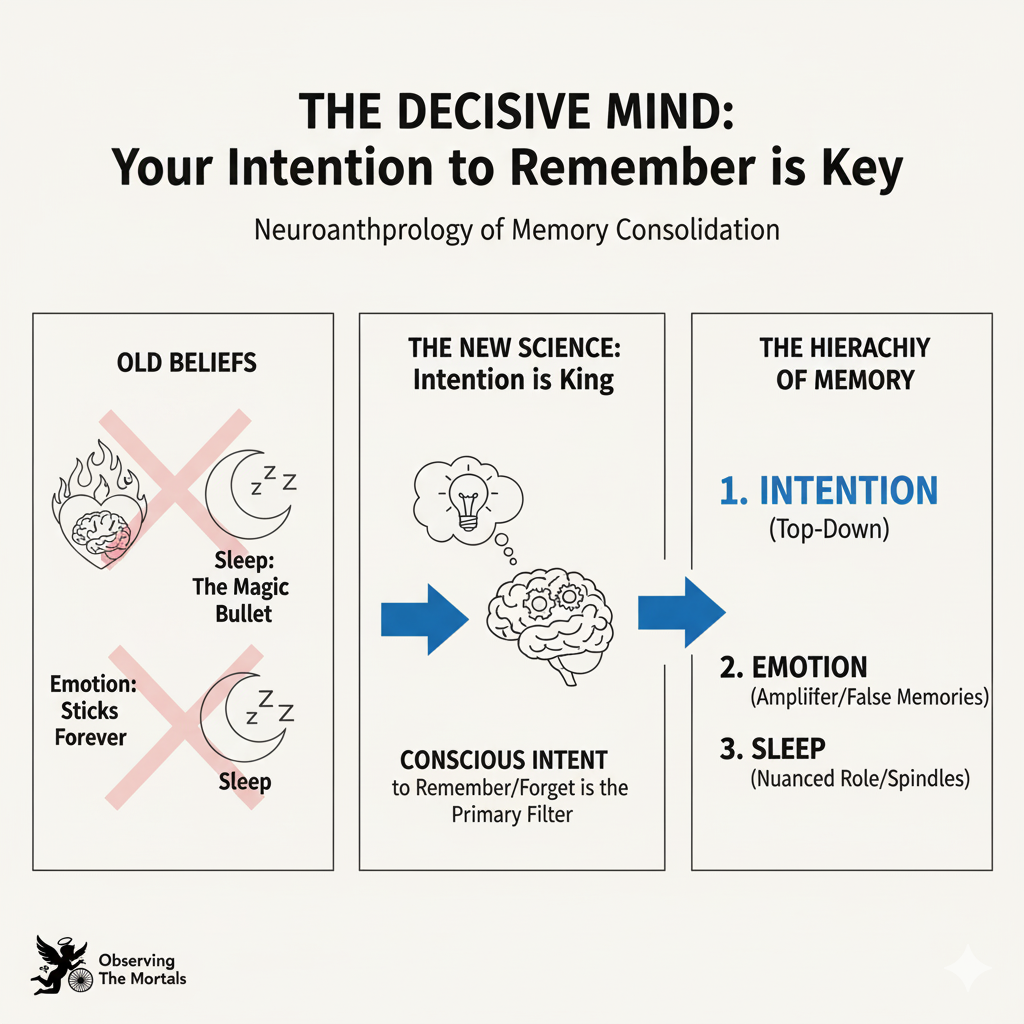

We all share a common understanding of how memory works. We believe that powerful, emotional events are burned into our minds forever, and that a “good night’s sleep” is the magic ingredient for solidifying what we learned during the day. But what if this common wisdom is wrong? A fascinating new study in neuroscience challenges both of these ideas, suggesting that the most powerful factor in shaping what we remember is not the emotional charge of an event, nor the act of sleeping on it, but a simple, conscious decision: the intention to remember. This case study explores the science that reveals we are, more than anything else, the primary architects of our own memory palace.

The Information Box

Syllabus Connection:

- Paper 1: Chapter 1.7 (The Biological Basis of Life/Behavior), Chapter 12 (New perspectives: Neuroanthropology, Cognitive Anthropology), Chapter 1.2 (Relationship with Psychology & Neuroscience)

Key Concepts/Tags:

- Neuroanthropology, Memory Consolidation, Directed Forgetting, Emotional Salience, Sleep Spindles, Cognitive Anthropology

The Setting: Who, What, Where?

The setting is a cognitive neuroscience lab, with research led by Dr. Laura Kurdziel and published in Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. The study involved a clever experimental design known as a “directed forgetting” task. Participants were shown a series of words—some emotionally negative, some neutral—and after each word, they were explicitly instructed to either “remember” or “forget” it. Their memory for these words was then tested 12 hours later, after either a period of wakefulness or a night of sleep (during which some participants’ brain activity was monitored with an EEG).

The Core Argument: Why This Study Matters

This research fundamentally reorders the hierarchy of factors that influence the creation of long-term memories.

- Intention is King (“Top-Down Instruction”): The single most significant finding is that the explicit instruction to “remember” was a far more powerful predictor of successful recall than the emotional content of the word. This demonstrates the primacy of “top-down” cognitive control. Our conscious intention to tag information as “important” appears to be the most crucial signal for the brain to begin the process of storing it for the long term.

- Emotion: A Double-Edged Sword: Emotion is not irrelevant, but its role is secondary and surprisingly complex. The study found that:

- It can amplify the instruction to remember (negatively charged words that were cued for recall were remembered slightly better).

- It can also significantly increase the likelihood of creating false memories (participants were more likely to “remember” seeing a negative word that wasn’t actually on the list).

- The Nuanced Role of Sleep: The study surprisingly found that simply sleeping did not provide a general, overall boost to memory performance compared to a similar period of being awake. However, specific brain wave patterns during sleep did matter. Sleep spindles, for instance, were linked to better recall of emotional words, while slow-wave sleep was linked to poorer recall, suggesting it might be involved in the active process of forgetting irrelevant information.

The Anthropologist’s Gaze: A Critical Perspective

- Neuroanthropology and the Basis of Culture: This study is a foundational piece for neuroanthropology. Culture, at its core, is a system of shared memories that are transmitted across generations. This research reveals a key cognitive mechanism for that transmission. It suggests that cultural learning—in rituals, in schools, in storytelling—is not just a passive absorption of emotional experiences, but an active, intentional process where a society “instructs” its members on what is important to remember.

- From Individual to Collective Memory: While the study focuses on individual memory, an anthropologist would immediately see its implications for collective memory. How does a nation or a community “instruct” its members to remember certain historical events (like victories) and to “forget” others (like shameful episodes)? This is done through official textbooks, national holidays, monuments, and public narratives. These are all forms of large-scale “directed forgetting” and “directed remembering” that shape a group’s identity.

- A Challenge to Freudian Models?: The finding that our conscious, executive brain functions have such a strong command over memory offers a fascinating counterpoint to classical Freudian psychoanalytic theories, which often emphasize the power of the unconscious and the inescapable nature of repressed (and highly emotional) memories. This study highlights the significant power of our conscious mind to act as the curator of its own content.

The Exam Angle: How to Use This in Your Mains Answer

- Types of Questions Where It can be Used:

- “Discuss the biological basis of human behavior, with a focus on cognition.”

- “What are the new perspectives and emerging branches in anthropology, such as neuroanthropology?”

- Essay: On themes of memory, consciousness, or the human mind.

- Model Integration:

- On Neuroanthropology (Paper 1, Ch 12): “Neuroanthropology explores the neural underpinnings of human behavior and culture. For example, a recent study on memory demonstrated that ‘top-down’ cognitive instruction to remember something is a more powerful factor in memory consolidation than the ‘bottom-up’ emotional content of the memory itself, revealing the power of conscious intent.”

- On the Biological Basis of Behavior: “The biological basis of memory is complex, involving a hierarchy of controls. A 2025 study in ‘Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience’ showed that our conscious intention to remember or forget has a greater impact on long-term recall than even the emotional charge of the memory, highlighting the crucial role of the brain’s executive functions.”

- For an Essay on the Mind: “Our understanding of memory is shifting from a passive model to an active one. Recent neuroscientific research suggests we are the primary architects of our own ‘memory palace,’ with our conscious intention to remember or forget being a more powerful influence than either the emotional salience of an event or even the general act of sleep itself.”

Observer’s Take

We often feel that our memories happen to us—that powerful, emotional events are seared into our minds against our will. This research offers a more empowering, and perhaps more accurate, view. It suggests that we are the active curators of our own mental world. Our attention and our intention are the most powerful tools we have for deciding which of today’s countless experiences will be selected, consolidated, and filed away to become tomorrow’s long-term memories. While emotion adds color and sleep helps with the filing, it is our conscious, decisive mind that appears to be the true gatekeeper of our past.

Source

- Title: Top-Down Instruction Outweighs Emotional Salience: Nocturnal Sleep Physiology Indicates Selective Memory Consolidation

- Author: Laura Kurdziel, et al.

- Publication: Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience

- News Source: Frontiers / Neuroscience News