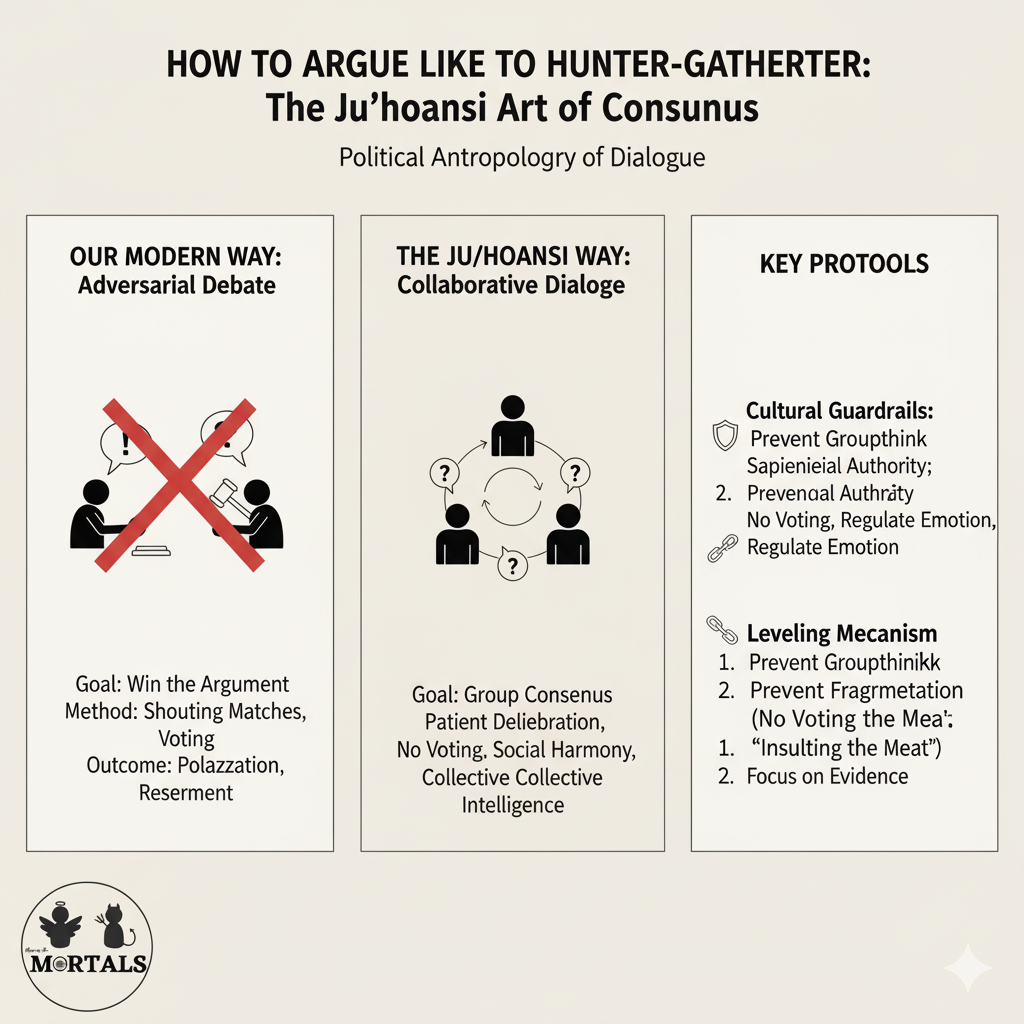

Our modern world is saturated with debate. From parliamentary shouting matches to social media pile-ons, our public discourse is often an adversarial battle, a zero-sum game focused on “winning” arguments rather than solving collective problems. But what if a political system, honed over 100,000 years, holds the secret to a more effective way of making group decisions? This case study delves into the world of the Ju/’hoansi hunter-gatherers of the Kalahari, whose sophisticated protocol for achieving consensus offers a profound and urgently needed alternative to our own culture of polarization.

The Information Box

Syllabus Connection:

- Paper 1: Chapter 4 (Political Anthropology: Stateless Societies, Social Control), Chapter 1.8 (Research Methods: Fieldwork Traditions)

- GS-4/Essay: Ethics, Social harmony, Governance

Key Concepts/Tags:

- Ju/’hoansi (!Kung San), Consensus, Deliberation, Leveling Mechanism, Stateless Society, Political Anthropology, Dialogue vs. Debate

The Setting: Who, What, Where?

This case study is centered on the Ju/’hoansi (also known as the !Kung San or G/wi), a traditionally egalitarian and mobile hunter-gatherer society of the Kalahari Desert in Southern Africa. The analysis draws on the classic fieldwork of anthropologists like George Silberbauer, who documented the famous “Dilemma of the Deserted Husband,” and Megan Biesele. It examines the Ju/’hoansi’s highly developed system of consensus-based decision-making, a social technology for resolving complex problems without formal leaders or voting.

The Core Argument: Why This Study Matters

This is not a description of a “primitive” political system, but an analysis of a sophisticated “social protocol” for achieving high collective intelligence and social harmony.

- The Goal is Consensus, Not Victory: Unlike a Western debate, the goal of a Ju/’hoansi deliberation is not for one side to “win” and the other to “lose.” Because the band is highly interdependent, a “knockout blow” in an argument would be self-defeating. The ultimate goal is to arrive at a solution that everyone in the group can live with, thereby preserving the social harmony that is essential for their collective survival.

- “Cultural Guardrails” to Avoid Failure: The Ju/’hoansi protocol has a set of built-in rules or “guardrails” to avoid the two main pitfalls of group decision-making:

- To Prevent Groupthink: They encourage widespread participation, ensuring that everyone—man, woman, old, and young—has a say. Leaders practice “sapiential authority,” meaning they guide the conversation but state their own opinions late, to avoid biasing the outcome.

- To Prevent Fragmentation: They strictly avoid voting, which is seen as a polarizing act that creates public winners and losers, leading to resentment. They also regulate emotion, temporarily adjourning discussions if they become too heated.

- The Separation of Ego from Idea: This is a key insight and a powerful leveling mechanism. Once an idea is spoken, it becomes public property. It is no longer “your” idea or “my” idea. This allows the group to rigorously and skeptically critique the idea based on evidence without it becoming a personal attack on the individual who suggested it. This is similar in function to the famous practice of “insulting the meat.”

The Anthropologist’s Gaze: A Critical Perspective

- “Dialogue” vs. “Debate”: The essay brilliantly uses the work of physicist David Bohm to frame the Ju/’hoansi method as a form of “dialogue” (a collective inquiry into a shared meaning) rather than “debate” (a fight to prove who is right). This is a powerful analytical distinction that critiques the adversarial nature of much Western political and academic discourse. The Ju/’hoansi are engaged in a collaborative search for truth, not a rhetorical contest.

- A Self-Conscious Political Philosophy: This analysis powerfully refutes the old Durkheimian view of “primitive” societies as unthinking conformists. The Ju/’hoansi are presented as highly self-conscious political actors who know that their process leads to better outcomes. They have a sophisticated, articulated philosophy of good governance, with one informant stating, “It’s necessary to draw on the strengths of each person, to minimise the chances that decisions will be made on the basis of the weakness of one or a few persons.”

- The Challenge of Scale: The author rightly acknowledges the primary limitation and critical question: this system is optimized for small, face-to-face groups with high levels of mutual interdependence and shared values. The great challenge is how, or even if, its core principles of genuine dialogue and ego-detachment can be adapted to the large-scale, anonymous, and diverse societies of modern nation-states and digital communities.

The Exam Angle: How to Use This in Your Mains Answer

- Types of Questions Where It can be Used:

- “Analyze the political organization and mechanisms of social control in stateless societies.”

- “The concept of ‘law’ in simple societies is fundamentally different from that in state societies. Discuss.”

- GS-4 (Ethics)/Essay: On topics of consensus building, emotional intelligence, and public discourse.

- Model Integration:

- On Political Organization: “Stateless societies like the Ju/’hoansi possess sophisticated political systems based on consensus, not command. As seen in the classic ‘Dilemma of the Deserted Husband,’ their decision-making involves prolonged, inclusive deliberation and the strict avoidance of polarizing practices like voting, all aimed at preserving social harmony.”

- On Social Control: “Social control among the Ju/’hoansi is maintained through powerful cultural guardrails on public discourse. They regulate emotion by adjourning heated debates and detach ideas from individual egos, allowing for rigorous, evidence-based critique without personal conflict. This prioritizes collective intelligence over individual victory.”

- For a GS-4/Essay Answer: “The consensus-based ‘protocol’ of the Ju/’hoansi offers a powerful ethical alternative to adversarial debate. By prioritizing collective inquiry (‘dialogue’) over individual ‘winning,’ their system provides a timeless model for resolving conflict and achieving better outcomes in any small group, from a family to a corporate board.”

Observer’s Take

In an age of digital shouting matches and deepening political polarization, the Ju/’hoansi protocol feels like a message from a wiser past. It is a powerful reminder that “debate”—the art of fighting to win—is only one mode of communication, and often the least effective for solving real, collective problems. The Ju/’hoansi teach us the ancient and more difficult art of “dialogue”—the shared, patient, and humble inquiry into a solution that everyone can live with. Their system, honed by millennia of survival in a harsh and unforgiving environment, is a testament to the idea that a group’s greatest strength lies not in the rhetorical brilliance of its leaders, but in its collective ability to truly think, and feel, together.

Source

- Title: The Ju/’hoansi protocol

- Author: Vivek V Venkataraman

- Publication: Aeon

- Link: https://aeon.co/essays/what-the-ju-hoansi-can-tell-us-about-group-decision-making