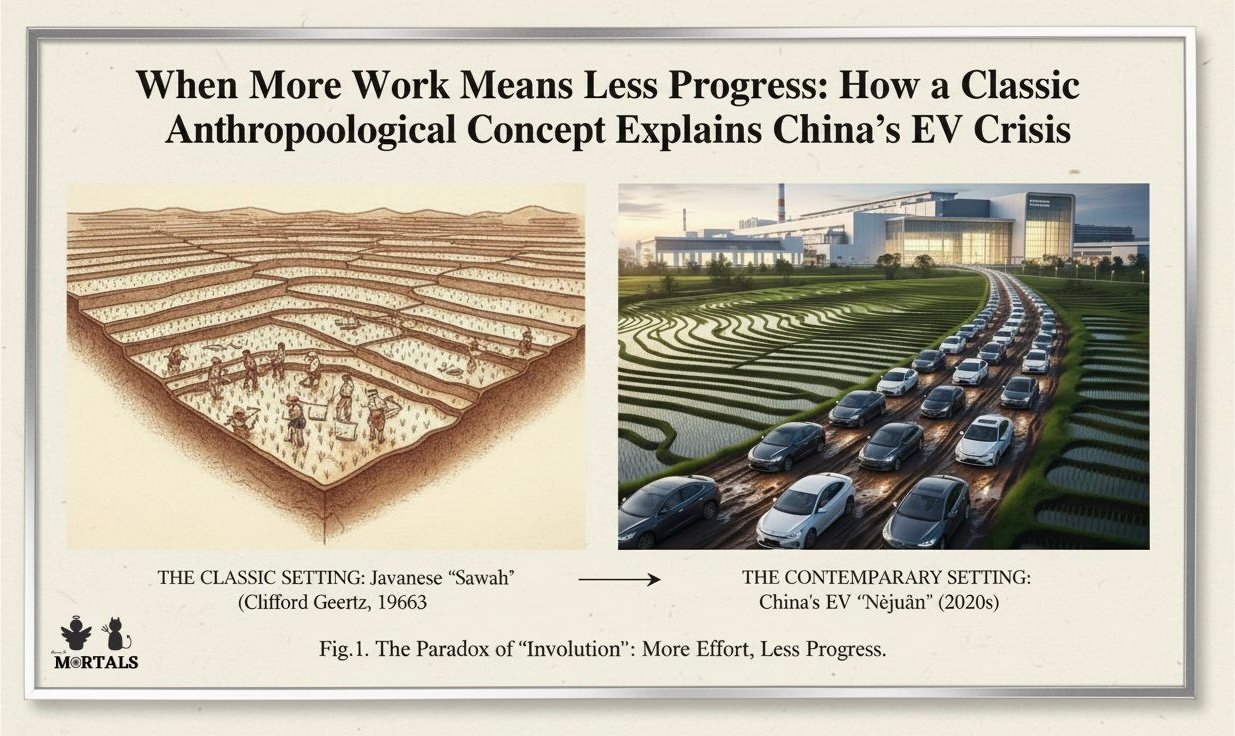

On the surface, China’s Electric Vehicle (EV) industry is a marvel of hyper-modernity and futuristic ambition. Yet, beneath the dazzling showrooms and record production numbers, the sector is caught in a self-destructive spiral. Firms are locked in brutal price wars, selling cars at a loss simply to survive in a massively overcrowded market. This phenomenon of frantic, counterproductive competition is so widespread in China that it has its own buzzword: nèijuǎn, or “involution.” What is truly fascinating is that this cutting-edge business term has its roots not in economics, but in a 1963 anthropological study of a Javanese rice paddy, authored by the legendary Clifford Geertz.

The Information Box

Syllabus Connection:

- Paper 1: Chapter 6 (Anthropological Theories: Clifford Geertz), Chapter 10 (Ecological Anthropology), Chapter 3 (Economic Anthropology)

- Paper 2: Chapter 8 (Social Change in India: Impact of Globalization)

Key Concepts/Tags:

- Involution, Clifford Geertz, Agricultural Involution, Neijuan, Economic Anthropology, Applied Anthropology

The Setting: Who, What, Where?

To understand this concept, we must look at two vastly different settings:

- The Classic Setting: The story begins with renowned anthropologist Clifford Geertz and his 1963 book, Agricultural Involution: The Processes of Ecological Change in Indonesia. His research focused on the intricate wet-rice (sawah) agricultural systems in Java, Indonesia, during the colonial period.

- The Contemporary Setting: The story’s modern chapter is set in the hyper-competitive Electric Vehicle (EV) manufacturing sector in China. After years of heavy state subsidies created massive overcapacity, the industry is now defined by what its participants call nèijuǎn—a state of intense internal competition.

The Core Argument: Why This Study Matters

The power of this case study lies in the direct parallel between a pre-industrial farming system and a high-tech modern industry. Geertz’s concept of involution provides the perfect analytical lens to understand the Chinese EV crisis.

- Geertz’s Original Concept (Agricultural Involution): Geertz observed that as Java’s population grew under Dutch colonialism, the wet-rice paddies simply absorbed more and more labor. Instead of innovating or expanding to new lands, the farming techniques became incredibly elaborate and complex. More people worked longer hours with greater intricacy, but the output per person did not increase. The system became more complicated but ultimately stagnated in terms of productivity. Geertz described this as a process of “treading water with increasing desperation”—a trap where more effort does not lead to more progress.

- The Modern Parallel (EV Involution / Nèijuǎn): China’s EV market is a perfect modern echo of this process. It is absorbing immense effort—colossal investments, rapid innovation, and relentless production—but the return per unit sold is collapsing due to vicious price wars. Companies are working harder, competing more fiercely, and producing more advanced cars, only to sell them at or below cost. Like the Javanese farmer adding one more meticulous step to their rice cultivation for no extra rice, the Chinese EV firm is slashing its price by another thousand yuan for no extra profit.

- The Shared Logic: The core pattern in both cases is diminishing (or negative) marginal returns on effort. The extra work no longer produces a net gain. It is a state of frenetic activity without meaningful advancement.

The Anthropologist’s Gaze: A Critical Perspective

- From Analysis to Metaphor: A critical perspective would note that the term’s modern usage is more of a powerful metaphor than a direct application of Geertz’s model. The underlying causes are different: Geertz’s involution was driven by population pressure in a closed colonial economy, while China’s is driven by state-led industrial policy and capitalist competition.

- The Social Life of a Concept: An anthropologist would be fascinated by how “involution” escaped academia to become a viral cultural buzzword in China. Nèijuǎn is now used by Chinese youth to describe the rat race in everything from the brutal university entrance exams (gaokao) to the exhausting “996” tech work culture. The term’s popularity signals a widespread societal feeling of meaningless, high-stakes competition.

- The Role of the State: In Java, the farmers were trapped by colonial policy. In the Chinese EV case, the state is both the architect of the problem (through subsidies that fueled oversupply) and the proposed solution (through forced consolidation). This highlights the immense power of the modern state in creating and trying to solve economic involution.

The Exam Angle: How to Use This in Your Mains Answer

- Types of Questions Where It Can Be Used:

- “Anthropological concepts have profound relevance in understanding contemporary global issues. Discuss.”

- “Analyze the impact of state policies on economic systems, using anthropological insights.”

- GS-3/Essay: On topics of industrial policy, competition, and the challenges of economic growth.

- Model Integration:

- On the Relevance of Anthropology: “The enduring relevance of anthropological theory is highlighted by the concept of ‘involution.’ Originally used by Clifford Geertz to describe a stagnating Javanese agrarian economy, the term has been adopted in modern China as nèijuǎn to diagnose the self-defeating hyper-competition in its EV sector, proving how classic concepts can illuminate contemporary paradoxes.”

- For Economic Anthropology: “The concept of ‘involution’ provides a powerful tool to analyze economic systems facing diminishing returns. Geertz applied it to a pre-industrial society, but its logic of ‘activity without progress’ is equally visible in China’s hyper-capitalist EV market, where intense price wars lead to massive effort for negative profits.”

- For a GS-3 Answer: “To avoid the ‘involution trap’—a state of counterproductive competition as currently seen in China’s EV industry—India’s industrial policy must be carefully calibrated. It should focus not just on boosting production, but on fostering sustainable market structures to prevent subsidy-driven overcapacity and destructive price wars.”

Mentor’s Take

The journey of “involution” from a Javanese rice paddy to a Chinese boardroom is a powerful lesson. It demonstrates that the patterns of human social and economic life, which anthropology seeks to understand, are remarkably durable. The trap of working harder and harder just to stay in the same place is not a feature of any particular time or technology; it is a recurring human dilemma. This case study is a potent reminder to always look for the deeper structures beneath the surface of events and to question whether our frantic activity is leading to genuine progress or just a more complicated form of running on the spot.