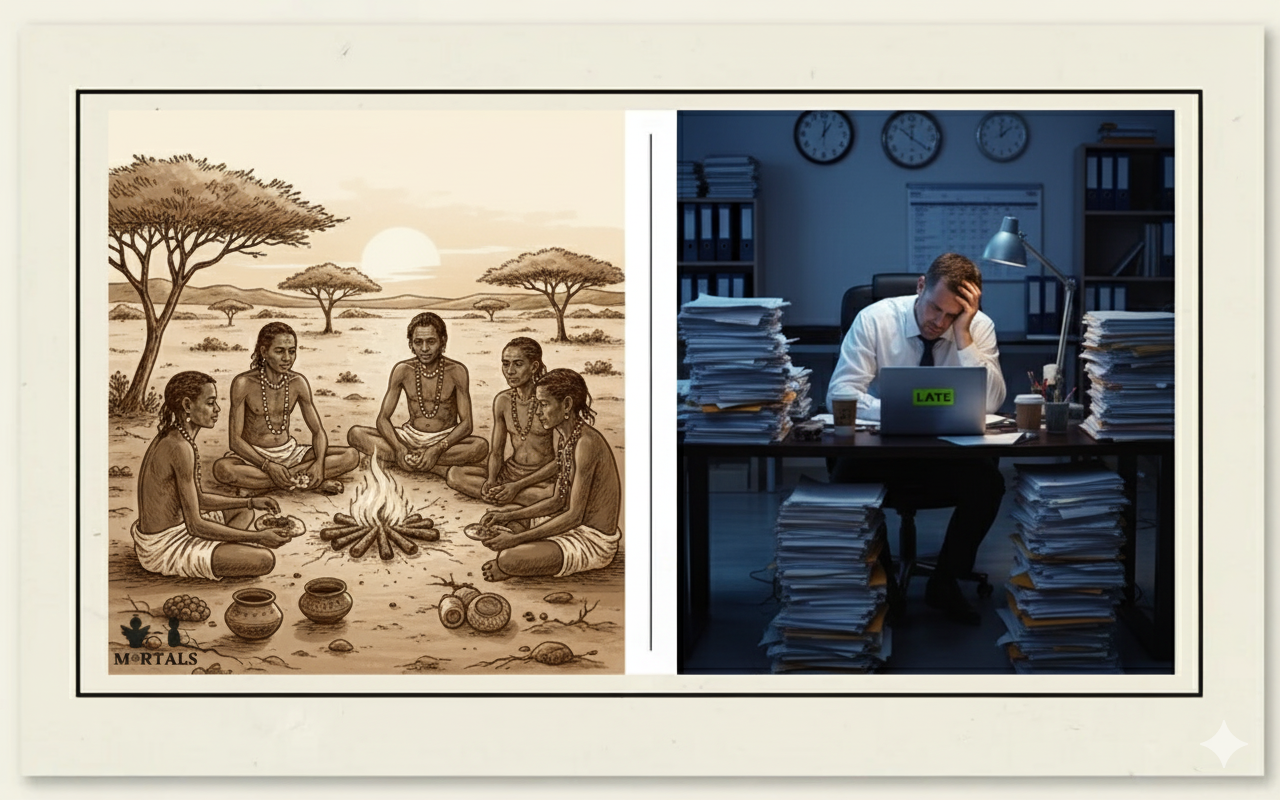

We live in the wealthiest and most technologically advanced societies in human history, surrounded by possessions our ancestors could never have imagined. Yet, we are also defined by stress, a feeling of constant scarcity, and the sense that we never have enough time. In the 1960s, the brilliant American anthropologist Marshall Sahlins proposed a radical and profound challenge to this modern condition. He looked at the data on hunter-gatherer societies—long dismissed as living lives that were “nasty, brutish, and short”—and came to a stunning conclusion: they were, in fact, the original affluent society. This case study explores Sahlins’s revolutionary idea that true wealth isn’t about having much, but about wanting little.

The Information Box

Syllabus Connection:

- Paper 1: Chapter 3 (Economic Anthropology), Chapter 6 (Anthropological Theories: Neo-evolutionism/Cultural Ecology), Unit 1.8 (Prehistoric Archaeology: Hunting and Gathering)

Key Concepts/Tags:

- Original Affluent Society, Marshall Sahlins, Hunter-Gatherers, Zen Economics, Reciprocity, Cultural Ecology

The Setting: Who, What, Where?

This is a theoretical work, not a single-site ethnography. The argument was famously put forward by Marshall Sahlins in his 1972 book, Stone Age Economics. To build his case, Sahlins synthesized a wide range of existing ethnographic data on foraging societies, drawing most heavily on studies of the !Kung San (also known as the Ju/’hoansi) of the Kalahari Desert and various Australian Aboriginal groups. He used their lives to launch a direct assault on the long-held Western assumption that human history is a simple story of progress from poverty to wealth.

The Core Argument: Why This Study Matters

Sahlins’s work was revolutionary because it completely inverted the traditional view of hunter-gatherer life. He argued that their societies were not defined by scarcity, but by a unique and efficient form of abundance.

- Flipping the Narrative of Scarcity: Sahlins first demolished the ethnocentric view that foragers lived in a state of constant, desperate struggle. He argued this was a projection of our own capitalist anxieties, where we have unlimited wants and are thus forever in a state of scarcity.

- The “Zen Road to Affluence”: This is the elegant heart of his theory. Sahlins proposed that there are two ways to achieve affluence:

- The Modern Way: To have infinite wants and attempt to produce infinitely to meet them (a path that guarantees scarcity).

- The Forager Way: To have few and finite wants that are easily satisfied from one’s environment. Hunter-gatherers, he argued, followed this “Zen road to affluence.” They weren’t poor; their material needs were simply different and easily met. Poverty is not having little, but the relation between means and ends.

- Redefining “Work” and “Leisure”: Based on quantitative data, Sahlins made a stunning calculation: the average hunter-gatherer adult spent only about 3 to 5 hours per day (15-20 hours a week) on subsistence activities (hunting, gathering). The rest of their time was leisure—spent on socializing, resting, storytelling, and ritual. This stood in stark contrast to the grueling labor of early agriculturalists and modern industrial workers.

- Other Markers of Affluence: Their affluence was also reflected in a highly varied and nutritious diet, their freedom of movement (mobility was their answer to local scarcity), and a profound lack of interest in accumulating material possessions, which would only be a burden for a nomadic group.

The Anthropologist’s Gaze: A Critical Perspective

Sahlins’s powerful thesis, while influential, has also been subject to important critiques.

- A Romanticized View?: The most significant critique is that Sahlins may have romanticized forager life. In his focus on their leisure and zen economics, did he underplay the very real hardships they faced, such as high infant mortality, frequent disease, and the constant threat of violence or starvation during droughts or lean seasons?

- What Counts as “Work”?: Some later anthropologists re-examined the data on working hours and argued Sahlins’s calculations might be too low. They questioned the definition of work—is time spent making tools, repairing huts, or processing food “work” or “leisure”? The line is often blurry.

- The Context of Marginal Lands: The hunter-gatherer groups Sahlins used as examples had often been pushed into some of the world’s most marginal environments (like deserts) by encroaching agricultural and state societies. A critical question is whether their “wanting little” was a deep-seated cultural philosophy or a pragmatic adaptation to living in resource-poor environments where material accumulation was simply not an option.

The Exam Angle: How to Use This in Your Mains Answer

- Types of Questions Where It Can be Used:

- “Critically examine the economic systems of hunter-gatherer societies.”

- “The concept of ‘scarcity’ is not universal but culturally constructed. Discuss.”

- GS/Essay: “Modern society’s definition of ‘development’ needs to be re-evaluated. Comment.”

- Model Integration:

- On Hunter-Gatherer Economy: “Contrary to the traditional Hobbesian view of a life of scarcity, Marshall Sahlins, in his concept of the ‘original affluent society,’ argued that hunter-gatherers achieved affluence by having limited and easily satisfied wants, allowing them to meet their needs with only 15-20 hours of work per week.”

- On Economic Anthropology: “Sahlins’s work fundamentally challenged the formalist assumption that all economies are based on a universal principle of scarcity. By proposing a ‘Zen road to affluence’ for foragers, he demonstrated that wealth and poverty are culturally relative concepts, not absolute measures of material accumulation.”

- For a Critique of Development: “The anthropological concept of the ‘original affluent society’ provides a powerful critique of modern development paradigms. It forces us to question whether a society that works longer hours for more possessions is truly more ‘advanced’ than a foraging society that prioritized leisure and community by desiring little.”

Observer’s Take

Sahlins’s idea is indeed “soulful.” Its enduring power lies not just in correcting the ethnographic record about our ancient ancestors, but in its ability to hold up a mirror to our own society. It forces us to ask deeply uncomfortable questions about our modern definitions of wealth, work, progress, and a well-lived life. The “original affluent society” is a radical concept because it suggests that the path to human well-being might not always be forward, into ever-more production and consumption, but perhaps requires a look backward, to a more balanced and sustainable understanding of what it means to have “enough.”