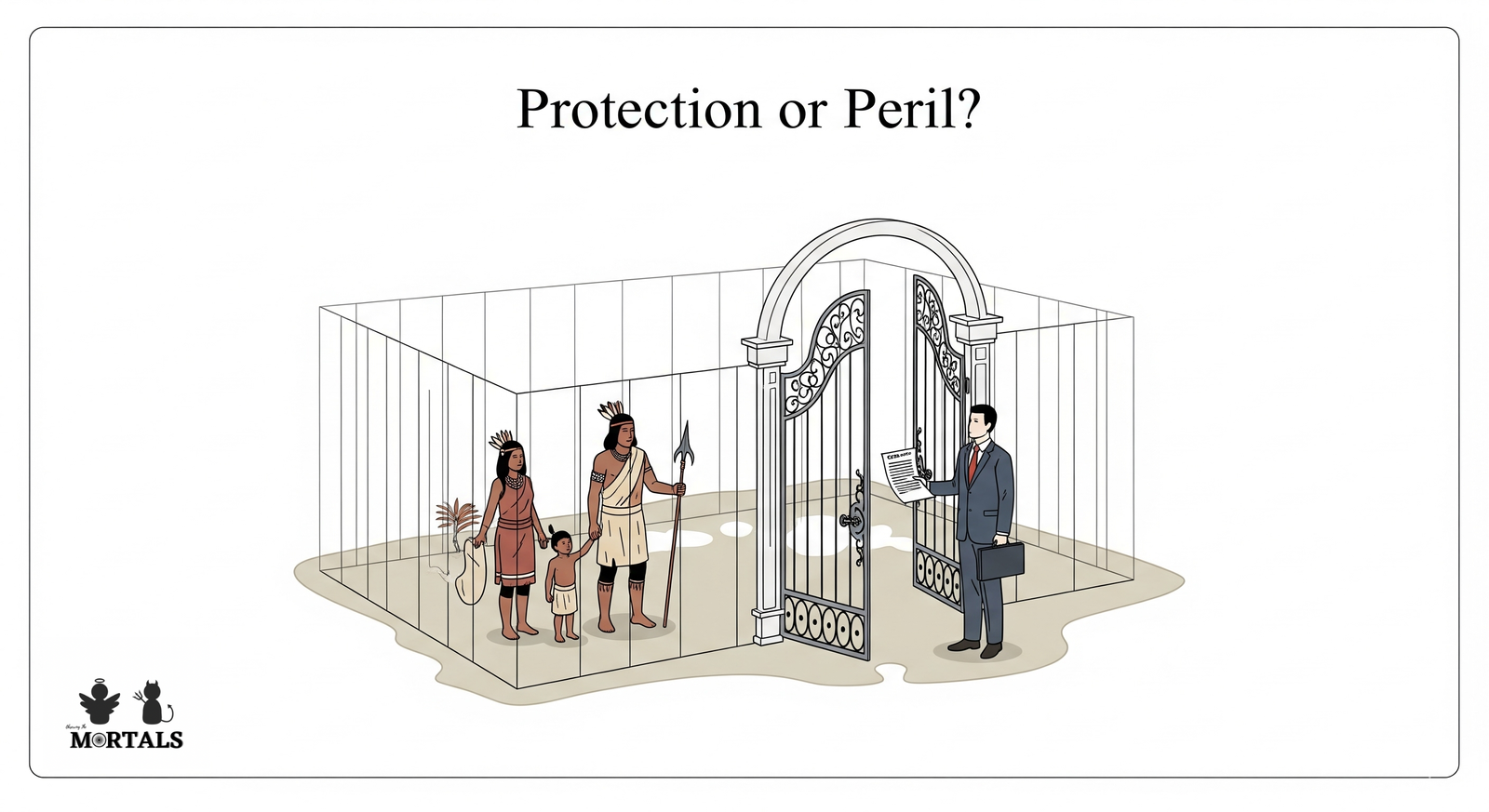

For decades, Indian law has treated tribal land like a fortress, protected by a wall of regulations designed to prevent it from being sold or lost to non-tribal outsiders. This “protective cage,” while well-intentioned, has been criticized for locking tribal communities out of economic opportunities, leaving vast tracts of land unproductive. Now, the Maharashtra government is proposing to open a gate in this fortress with a new Bill allowing tribal farmers to lease their barren land to private companies. Proponents hail it as a path to a steady income and empowerment, while critics fear it could be a backdoor to a new and insidious form of exploitation. This case study delves into a high-stakes policy experiment that could redefine the future of tribal land rights in India.

The Information Box

Syllabus Connection:

- Paper 2: Chapter 6 (Problems of Tribal Communities: Land Alienation; Tribal Administration), Chapter 8 (Social Change)

- Paper 1: Chapter 3 (Economic Anthropology), Chapter 4.3 (Legal Anthropology), Chapter 9 (Applied Anthropology)

Key Concepts/Tags:

- Tribal Land Alienation, Economic Development, Legal Pluralism, Applied Anthropology, Maharashtra, Market Integration

The Setting: Who, What, Where?

This case study is centered on a proposed Bill by the Maharashtra State Government that aims to amend the laws governing tribal land. The core mechanism of the Bill is to create a legal framework for tribal landowners to enter into lease agreements with private companies or industrialists for their officially designated “barren” (uncultivable) land. The key actors are the state’s Revenue Ministry, the tribal communities in districts like Palghar and Nandurbar who have reportedly requested this change, and the political opposition, which has raised alarms about potential exploitation.

The Core Argument: Why This Study Matters

This proposed law is not a minor tweak; it represents a fundamental strategic shift in the state’s approach to tribal land and economy.

- A Paradigm Shift: From Protection to Market Participation: The traditional legal approach has been purely protectionist, focusing on preventing the sale of tribal land. The government argues that this has led to a situation where unproductive land generates no income. This Bill marks a clear shift towards a market-participation model, aiming to convert a “dead” asset (barren land) into a source of steady income (a proposed minimum of ₹50,000 per acre annually).

- Decentralizing Bureaucracy: A significant procedural change is the move to decentralize the approval process. Previously, any such proposal would have to be cleared at the State Secretariat (Mantralaya) in Mumbai, a long and arduous process. The new Bill proposes to shift this power to the local District Collector, theoretically making the process faster and more accessible for tribal landowners.

- A New Model of “Partnership”: The government is framing this as a “partnership” between tribal farmers and industrialists. It is presented as a win-win scenario: tribal families get a secure income while retaining ownership rights, and industry gets access to land for development projects.

The Anthropologist’s Gaze: A Critical Perspective

An anthropological lens reveals the deep complexities and potential risks hidden beneath the surface of this seemingly straightforward policy.

- The Slippery Slope of “Barren Land”: An anthropologist would immediately question the official definition of “barren.” Is this land truly empty and unproductive? Or is it used for vital, informal subsistence activities like cattle grazing, foraging for Minor Forest Produce, or as common village lands (gairan) that are crucial for the poorest families? The official classification of land often overlooks its real-world, multi-faceted use. There is a critical risk that this could be the first step toward the eventual leasing of more fertile and vital lands.

- The Myth of Equal Negotiation: The Bill assumes a mutual agreement between two equal parties. A critical anthropological perspective would highlight the immense power asymmetry between an individual, often resource-poor, tribal farmer and a large, legally-savvy private corporation. The risk of coercive contracts, unfair terms, and exploitation is extremely high, regardless of a legally mandated “minimum rent.”

- Long-Term Social and Ecological Disruption: What happens to a community when a large-scale private project is established on its periphery? An anthropological analysis would look beyond the lease rent to the potential for massive social, cultural, and ecological disruption. This includes changes in local labor markets, the influx of migrant workers, pressure on local resources like water, and the erosion of the traditional agrarian social structure.

The Exam Angle: How to Use This in Your Mains Answer

- Types of Questions Where It Can be Used:

- “The issue of tribal land alienation has taken new forms in the era of liberalization. Discuss.”

- “Critically analyze the impact of market integration on tribal economies.”

- GS-2/3: “Discuss the challenges in balancing industrial development with the land rights of tribal communities.”

- Model Integration:

- On Land Alienation: “While historical land alienation often involved forceful seizure, contemporary policies are creating new pathways. For example, the proposed Maharashtra Bill allowing the ‘leasing’ of barren tribal land to private firms represents a shift from a protectionist to a market-based model, raising critical new questions about the potential for ‘development-induced’ dispossession.”

- On Tribal Development: “A central debate in tribal development is how to unlock the economic potential of tribal assets without causing exploitation. The Maharashtra government’s proposal to allow leasing of barren land is a case in point, attempting to provide income but facing severe criticism for potentially weakening the safeguards against land alienation.”

- For a GS Answer: “Recent policy shifts, such as Maharashtra’s proposed Bill for leasing tribal lands, highlight the ongoing tension between safeguarding vulnerable communities and promoting industrial growth. The success of such models hinges on creating robust regulatory mechanisms to address the inherent power asymmetry between tribal landowners and private corporations.”

Observer’s Take

The proposed Maharashtra Bill is a perfect microcosm of the central dilemma in tribal development today. The old “protective cage” model, designed to prevent exploitation, has also been accused of preventing economic growth. Simply opening the cage door to the market, however, carries immense risks. This policy is a high-stakes experiment. Its outcome will depend entirely on the strength of the legal safeguards and the ability of the local administration to act as an impartial and powerful protector of tribal interests, not merely as a facilitator for private industry. It will be a critical test of whether “partnership” can truly be a path to empowerment, or if it will simply become a new name for an old story of dispossession.