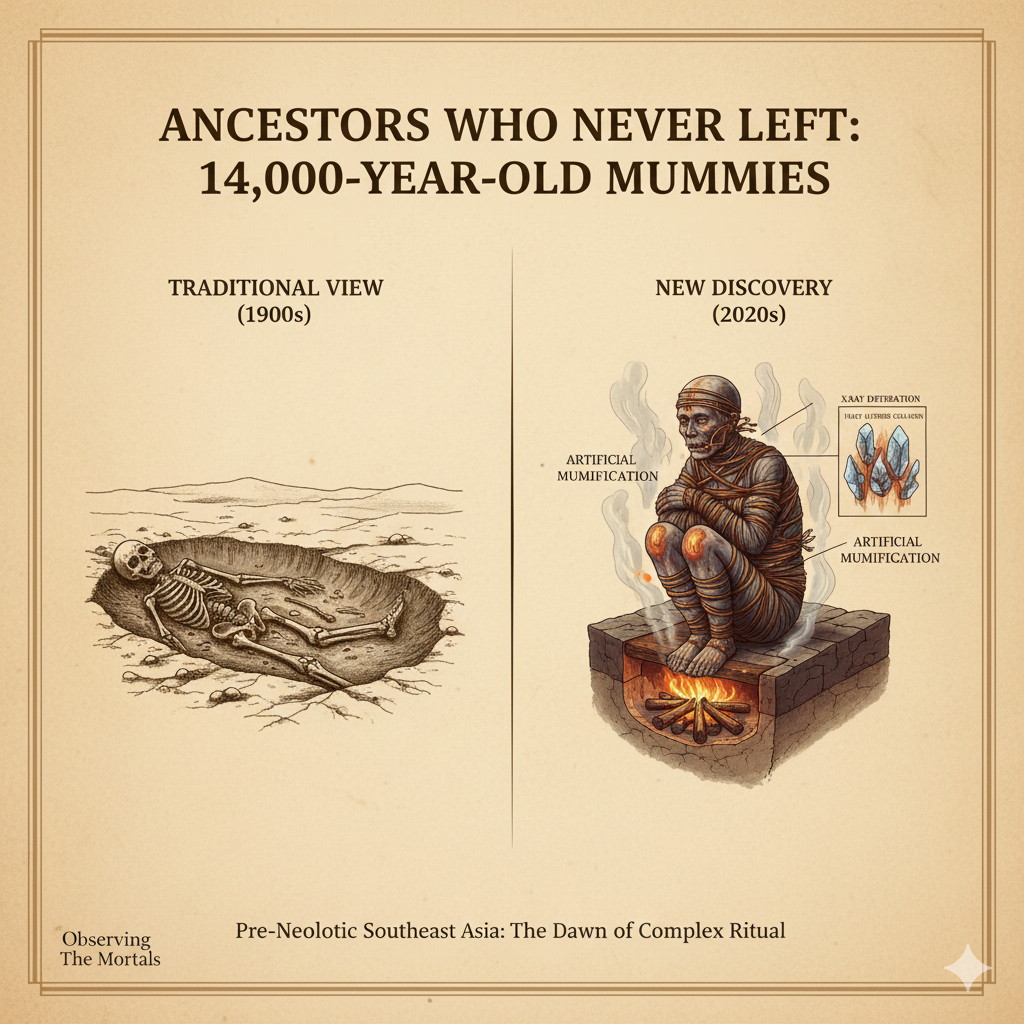

When we think of mummification, we often picture the elaborate, linen-wrapped bodies of ancient Egypt. But a groundbreaking new study from Southeast Asia is forcing us to completely rethink this story. Archaeologists have uncovered stunning evidence that pushes back the dawn of artificial mummification by five millennia, to a time long before the first farms or cities. This is a story of archaeological detective work, where modern science has been used to solve an ancient puzzle and, in the process, has revealed the unexpectedly sophisticated technical skills and deep spiritual world of our pre-farming ancestors.

The Information Box

Syllabus Connection:

- Paper 1: Chapter 1.3 (Archaeological Anthropology), Chapter 1.8 (Prehistoric Archaeology: Mesolithic), Chapter 5 (Anthropology of Religion: Disposal of the Dead, Ancestor Worship)

Key Concepts/Tags:

- Artificial Mummification, Pre-Neolithic Burials, Bio-archaeology, Symbolic Thinking, Ancestor Worship, Southeast Asian Archaeology

The Setting: Who, What, Where?

This case study is based on a major study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences by an international team of scientists, including Hsiao-chun Hung of the Australian National University. Their research spanned 11 pre-Neolithic (pre-farming) burial sites across Southeast Asia. For decades, archaeologists had been puzzled by the remains at these sites, which dated from about 12,000 to 4,000 years ago. The bodies were often found in unusual, tightly crouched or squatting postures, a position difficult to achieve if buried soon after death.

The Core Argument: Why This Study Matters

This research is not just about a new, earlier date for mummification; it fundamentally upgrades our understanding of the cultural and cognitive capabilities of pre-agricultural humans.

- A 5,000-Year Leap Back in Time: The central finding is the conclusive evidence of artificial mummification dating back at least 14,000 years. This shatters the previous record held by the Chinchorro mummies of Chile (around 7,000 years ago) and establishes Southeast Asia as the site of the world’s oldest known mummification practice.

- Solving the Puzzle with Science: The study deciphers the exact mortuary technique. Using advanced methods like X-ray diffraction and spectroscopy, the scientists found unique heat signatures on the bones. The evidence points to a process where bodies were tightly bound and then gently heated and smoked over low fires for long periods. This process desiccated and preserved the body, explaining both the crouched posture and the clustered burn marks on exposed areas like knees and foreheads.

- Proof of Early Symbolic and Spiritual Complexity: This is the most profound anthropological insight. This complex, labor-intensive process served no practical purpose; it was purely symbolic. It demonstrates that these pre-farming communities possessed remarkably sophisticated spiritual beliefs about the afterlife and the relationship between the living and the dead. The immense effort to preserve the body suggests a form of ancestor veneration, where the physical presence of the deceased was kept as part of community life for a period before final burial.

The Anthropologist’s Gaze: A Critical Perspective

- Challenging the “Neolithic Revolution” Narrative: This discovery is a powerful blow to the old, progressivist idea that cultural “complexity”—such as elaborate rituals, advanced technical skills, and deep symbolic thought—only began with the advent of agriculture (the Neolithic Revolution). It proves that hunter-gatherer societies had rich, complex, and spiritually advanced cultures thousands of years before the first crops were sown.

- The Power of Scientific Archaeology: This case is a perfect example of how modern scientific techniques are transforming archaeology. A long-standing mystery based on visual observation (the posture) was solved through molecular-level analysis of the bones. This provides a much deeper and more certain understanding of past human behavior than traditional methods alone could achieve.

- Ethno-archaeological Parallels: The study’s comparison of this ancient practice to similar, ethnographically recorded traditions of smoking the dead in the New Guinea Highlands is a great example of ethno-archaeology. This method uses the knowledge of recent or contemporary cultures to build plausible and powerful interpretations of the archaeological record.

The Exam Angle: How to Use This in Your Mains Answer

- Types of Questions Where It Can be Used:

- “Discuss the cultural achievements of Mesolithic (pre-Neolithic) peoples.”

- “What is the role of scientific methods in modern archaeological anthropology?”

- “Analyze the evolution of religious beliefs and mortuary practices with archaeological evidence.”

- Model Integration:

- On Pre-Neolithic Culture: “The traditional view of pre-Neolithic societies as simple is being consistently overturned by modern archaeology. For instance, recent discoveries in Southeast Asia have revealed evidence of complex artificial mummification dating back 14,000 years, indicating highly sophisticated mortuary rituals and symbolic beliefs long before the advent of agriculture.”

- On Archaeological Methods: “The power of scientific techniques in archaeology is profound. The use of X-ray diffraction to analyze pre-Neolithic bones from Southeast Asia, for example, allowed researchers to prove the practice of artificial mummification by identifying unique heat-induced changes in the bone’s crystal structure, solving a long-standing mystery.”

- On Religion: “The origins of complex religious behavior are ancient. The discovery of 14,000-year-old mummies in Southeast Asia suggests that a deep concern for the dead and rituals designed to keep ancestors connected to the living community—a form of ancestor veneration—were already well-established in pre-farming societies.”

Observer’s Take

This discovery is a profound reminder of how much of our shared human story is still hidden beneath the soil. It pushes back the dawn of one of humanity’s most fascinating practices: the refusal to simply let go of our dead. It demonstrates that thousands of years before the first pyramids were built, pre-farming peoples possessed both the technical skill and the deep spiritual need to preserve the bodies of their loved ones, keeping them as tangible members of their community. This isn’t just a story about ancient bones and fire; it’s a story about the ancient origins of human connection, memory, and our enduring desire to keep our ancestors close.