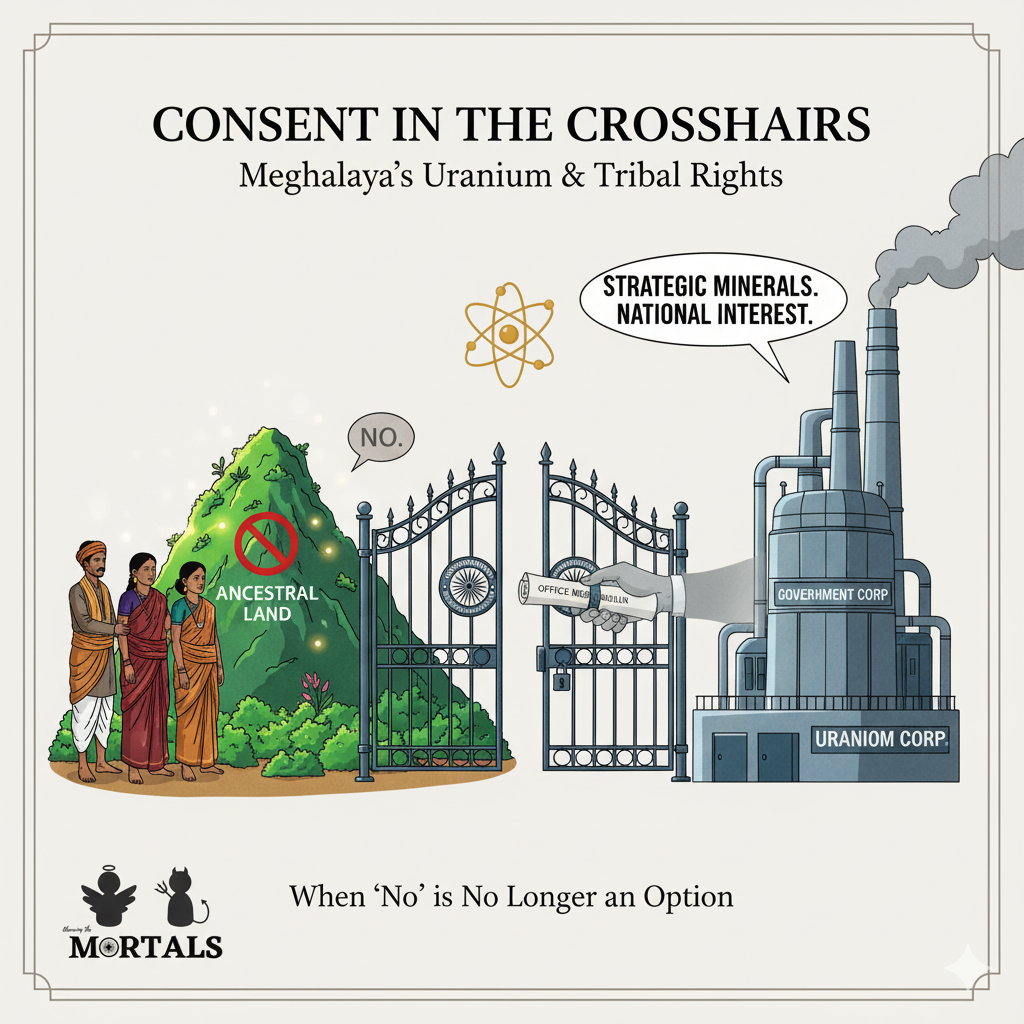

Uranium is a mineral of immense power. It can fuel a nation’s energy and security ambitions, but its extraction can leave irreversible scars on the land and lives of local communities. This paradox is currently at the heart of a tense conflict in the Khasi Hills of Meghalaya. For decades, local tribal groups have successfully resisted uranium mining on their ancestral lands. Now, the central government, armed with a simple executive order, is moving to bypass their opposition entirely. This case study examines how an “Office Memorandum” is being used to override a community’s long-standing refusal, creating a critical test for tribal rights, environmental democracy, and the very meaning of consent in modern India.

The Information Box

Syllabus Connection:

- Paper 2: Chapter 6 (Tribal India: Land Alienation, Impact of Industrialization; Tribal Administration: Sixth Schedule)

- Paper 1: Chapter 10 (Ecological Anthropology: Political Ecology), Chapter 4 (Political Anthropology: State vs. Indigenous Rights), Chapter 9 (Applied Anthropology)

Key Concepts/Tags:

- Uranium Mining, Khasi Tribe, Office Memorandum (OM), Free Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC), Sixth Schedule, Political Ecology, Resource Frontier

The Setting: Who, What, Where?

The conflict is centered in the uranium-rich areas of Domiasiat and Wahkaji in the Khasi Hills of Meghalaya. The key actors are the indigenous Khasi tribal groups, who have constitutional protections under the Sixth Schedule, and the Central Government of India. The instrument of conflict is a recent Office Memorandum (OM) issued by the Union Environment Ministry, which exempts projects involving “atomic, critical, and strategic minerals” from the mandatory public consultation process, a cornerstone of environmental clearance.

The Core Argument: Why This Study Matters

This case is a critical example of the erosion of democratic safeguards in the pursuit of strategic resources.

- Governance by Executive Fiat: The central issue is the use of an Office Memorandum, a low-profile executive instrument, to dismantle a fundamental democratic process. By removing the need for public consultation, the state is effectively silencing the voices of the very communities who will bear the heaviest environmental and social costs of uranium mining.

- A Direct Assault on “Free, Prior, and Informed Consent” (FPIC): The OM is a direct contradiction of the globally recognized principle of FPIC, which is the bedrock of indigenous rights. For decades, the Khasi people have clearly stated their opposition. The OM effectively signals, as the editorial notes, that “‘no’ is no longer an acceptable answer,” turning a right to consent into a mere formality to be bypassed.

- The “Resource Frontier” Mentality: This action reinforces a classic post-colonial problem where tribal lands are viewed by the central state not as ancestral homelands but as “resource frontiers” to be exploited for the “national interest.” The editorial powerfully connects this to the long and troubled history of uranium mining in Jharkhand, showing a consistent pattern of state behavior that disregards local objections and well-being.

- A Challenge to Constitutional Protections: The move puts the central government on a collision course with the special powers granted to the Khasi Hills Autonomous District Council under the Sixth Schedule of the Constitution, which gives it significant authority over land, forests, and resource management.

The Anthropologist’s Gaze: A Critical Perspective

- The Power of Labeling: An anthropologist would analyze how the state uses labels like “strategic mineral” to create a special class of resources. This label elevates the importance of uranium above all other considerations—local rights, environmental laws, democratic procedure—and is used to justify exceptional and often coercive measures. It’s a powerful discursive tool to legitimize overriding local consent.

- The Shadow of Niyamgiri: In that landmark judgment Niyamgiri case (2013) , the Supreme Court empowered the Dongria Kondh‘s Gram Sabha to veto a mining project on their sacred mountain. This Meghalaya case will be a critical legal test of whether that powerful precedent can be extended to protect communities under the Sixth Schedule, especially when the resource in question is labeled “strategic.”

- Procedural Violence: The parallel with the Jharkhand case, where official notices were allegedly issued in “unfamiliar languages,” is a key anthropological insight. This is a form of procedural violence. It means that a process can be legally “compliant” on paper while being completely unjust and inaccessible in reality. True “informed consent” requires access to information in a culturally and linguistically appropriate manner.

The Exam Angle: How to Use This in Your Mains Answer

- Types of Questions Where It Can be Used:

- “Analyze the conflict between national security imperatives and the rights of tribal communities.”

- “The Sixth Schedule provides a framework for tribal autonomy, but its efficacy is often challenged by the state. Discuss.”

- GS-2/3: “Public consultation is a vital part of environmental governance. Analyze the implications of diluting this process.”

- Model Integration:

- On Tribal Rights vs. Development: “The conflict between national interest and tribal rights is acutely visible in the proposed uranium mining in Meghalaya. The government’s use of an Office Memorandum to bypass mandatory public consultation with the Khasi tribes demonstrates how ‘strategic’ imperatives can be used to erode constitutional safeguards like the Sixth Schedule.”

- On Governance (GS-2/Anthro): “The use of executive instruments like Office Memorandums to bypass democratic procedures, as seen in the Meghalaya uranium mining case, raises serious concerns about governance. It undermines the principle of Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) and reduces local communities to mere bystanders.”

- Citing Precedents: “Faced with this executive overreach, the Khasi tribes may seek judicial recourse, banking on powerful precedents like the Supreme Court’s Niyamgiri (2013) judgment, which upheld the right of local communities to decide the fate of mining projects on their ancestral lands.”

Observer’s Take

The situation in Meghalaya’s uranium hills is far more than a local land dispute; it’s a critical test for the character of Indian democracy. It pits the state’s narrow definition of national security against its constitutional obligation to protect its indigenous citizens. The use of an executive order to effectively declare that a community’s decades-long “no” is no longer valid is a dangerous precedent. The true measure of a nation’s strength lies not just in the strategic resources it can extract from the ground, but in the respect and justice it affords to the people who have stewarded those lands for generations. Dialogue and consent are not obstacles to progress; they are the very foundation of a just and sustainable nation.