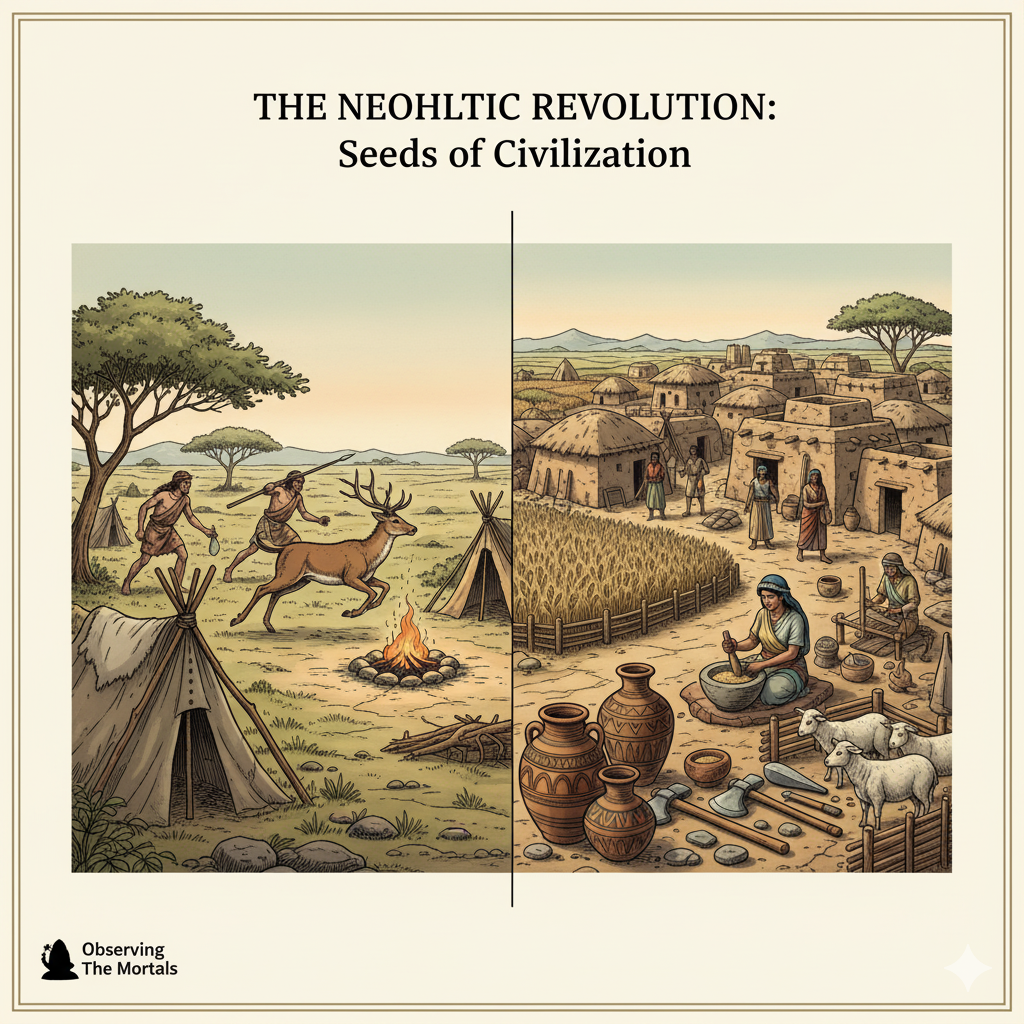

What was the most significant event in the human story? Was it the invention of the wheel, the discovery of fire, or the first steps on the moon? A strong case can be made that it was a much quieter moment: the instant one of our ancestors chose to plant a seed in the ground, deciding to grow food rather than chase it. In the early 20th century, the brilliant archaeologist V. Gordon Childe gave this profound shift a name that captured its immense consequences: the “Neolithic Revolution.” This case study explores his foundational concept of how the adoption of agriculture completely rewired human society and set the stage for the world we live in today.

The Information Box

Syllabus Connection:

- Paper 1: Chapter 1.8 (Prehistoric Archaeology: Neolithic), Chapter 3 (Economic Anthropology), Chapter 6 (Anthropological Theories: Neo-evolutionism)

- Paper 2: Chapter 1.1 (Indian Prehistory: Neolithic Period)

Key Concepts/Tags:

- Neolithic Revolution, V. Gordon Childe, Domestication, Oasis Theory, Urban Revolution, Sedentism

The Setting: Who, What, Where?

This is the world of V. Gordon Childe, a hugely influential Australian archaeologist who dominated British prehistory in the mid-20th century. Known for his sweeping, materialist synthesis of the past, his ideas were famously published in books like Man Makes Himself (1936) and What Happened in History (1942). Childe was not focused on a single site but was trying to build a universal model to explain the major technological and economic transformations in human prehistory, using archaeological data from across the “Fertile Crescent” of Southwest Asia and beyond.

The Core Argument: Why This Study Matters

Childe’s genius was to argue that the adoption of agriculture was not just a change in food-getting techniques; it was a total social, political, and economic revolution that irrevocably changed the course of human history.

- The “Neolithic Package”: He argued that once farming took root, a whole “package” of revolutionary changes inevitably followed:

- Sedentism: For the first time, people began to live in permanent, settled villages.

- Population Explosion: A more stable and abundant food supply allowed human populations to grow exponentially.

- New Technologies: Life in a village spurred new inventions like pottery (to store surplus grain), weaving (using plant and animal fibres), and more complex, polished stone tools.

- Private Property & Social Stratification: For the first time, land and surplus food became valuable, inheritable property. This, Childe argued, was the origin of social inequality, leading to the emergence of classes, leaders, and eventually, organized warfare to protect or seize resources.

- The “Oasis Theory”: Childe also proposed a cause for this revolution. He suggested that after the last Ice Age, the climate of Southwest Asia became drier, forcing humans, animals, and plants to cluster together in oases and river valleys. This close proximity (propinquity) gave humans an intimate knowledge of plant and animal life cycles, which eventually led to their domestication.

- The Precursor to Cities: For Childe, the Neolithic Revolution was the essential first step that made the next great transformation possible: the “Urban Revolution,” where the food surpluses generated by farmers allowed for the growth of cities, states, and specialized classes of priests, artisans, and rulers.

The Anthropologist’s Gaze: A Critical Perspective

Childe’s model was foundational, but modern archaeology has significantly revised it.

- “Revolution” or a Slow “Evolution”?: This is the most important critique. Armed with more precise dating techniques like radiocarbon dating, later archaeologists have shown that the transition to agriculture was not a sudden, dramatic “revolution.” It was a slow, messy, and very gradual evolutionary process that took thousands of years. Many groups experimented with part-time cultivation while continuing to hunt and gather for centuries.

- The Flawed “Oasis Theory”: Childe’s proposed cause for the revolution has also been largely disproven. Later archaeological and climatic research showed that the climate was actually getting wetter, not drier, when agriculture began, and that the earliest sites of domestication were in the hilly flanks of the Fertile Crescent, not in the oasis valleys.

- Was it a Good Thing?: Childe presented the revolution as a clear step forward for humanity. Many later scholars, most famously Jared Diamond, have challenged this view, calling agriculture “the worst mistake in the history of the human race.” They point to the downsides: a less varied and nutritious diet, the spread of epidemic diseases in crowded villages, the rise of back-breaking labor, and the birth of deep social and gender inequality.

The Exam Angle: How to Use This in Your Mains Answer

- Types of Questions Where It can be Used:

- “What were the major cultural and economic features of the Neolithic period?”

- “V. Gordon Childe described the adoption of agriculture as a ‘revolution.’ Critically evaluate this concept.”

- “Analyze the impact of the domestication of plants and animals on human society.”

- Model Integration:

- To define the concept: “The term ‘Neolithic Revolution,’ coined by archaeologist V. Gordon Childe, describes the profound social and economic transformation following the adoption of agriculture, which he argued led to sedentism, population growth, new technologies like pottery, and the emergence of social stratification.”

- To offer a critical view: “While V. Gordon Childe’s concept of a ‘Neolithic Revolution’ was foundational, modern archaeology has challenged his idea of a sudden event. The transition is now understood as a slow, evolutionary process that occurred over millennia, with many societies adopting a mixed subsistence strategy for a long time.”

- On its consequences: “As V. Gordon Childe argued, the Neolithic Revolution was the necessary precondition for the later Urban Revolution. The food surplus and settled populations generated by agriculture were essential for the emergence of the first cities, states, and specialized classes of artisans and rulers.”

Observer’s Take

V. Gordon Childe’s genius was his ability to look at scattered, silent prehistoric artifacts and weave them into a grand and powerful story of human transformation. While modern science has since refined or even overturned many of his specific details—it was an evolution, not a revolution; the oases weren’t the cause—his central insight remains unshakable. The decision to plant a seed was the most momentous act in human history. It set our species on an entirely new trajectory, leading to everything that followed: our villages, our cities, our states, our technologies, our inequalities, and the very foundations of the modern world. Childe’s “Neolithic Revolution” is a powerful reminder that the greatest changes often begin not with kings and battles, but with a quiet, fundamental shift in how we get our daily bread.