We all love a good story. But what if the stories and myths we tell are more than just entertainment? What if they are, in fact, sophisticated logical tools that human societies use to think through their most profound and difficult contradictions? This was the revolutionary idea of the great French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss. He believed that myths across the world shared a hidden, universal structure, like a musical score waiting to be read. This case study explores his genius by dissecting one myth—”The Story of Asdiwal”—to show how he “x-rayed” a simple tale to reveal the deep logic beneath.

The Information Box

Syllabus Connection:

- Paper 1: Chapter 6 (Anthropological Theories: Structuralism – Lévi-Strauss), Chapter 2.6 (Myth and Ritual), Chapter 5 (Anthropology of Religion)

Key Concepts/Tags:

- Structuralism, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Myth, Binary Oppositions, The Story of Asdiwal, Tsimshian

The Setting: Who, What, Where?

This case study is centered on the work of Claude Lévi-Strauss, the founder of French Structuralism in anthropology, a school of thought that sought to uncover the universal underlying patterns of human cognition. The specific analysis comes from his influential 1958 essay, “The Story of Asdiwal.” The myth itself belongs to the Tsimshian people, an indigenous group from the Pacific Northwest Coast of British Columbia, Canada. The story follows the life, travels, and marriages of a hero named Asdiwal, whose journey is filled with famine, plenty, and supernatural events.

The Core Argument: Why This Study Matters

Lévi-Strauss’s analysis fundamentally changed the way anthropologists approached myth. He argued that the surface-level plot of a story is just a distraction; the real meaning lies in its hidden structure.

- Myth as a Logical Tool: Lévi-Strauss’s first radical claim was that myths are not pre-scientific, fanciful, or arbitrary. He argued they have a rigorous, underlying logical structure, much like a language. The primary function of a myth, he proposed, is to be a tool for mediating and providing an imaginary resolution to fundamental cultural contradictions that cannot be solved in real life.

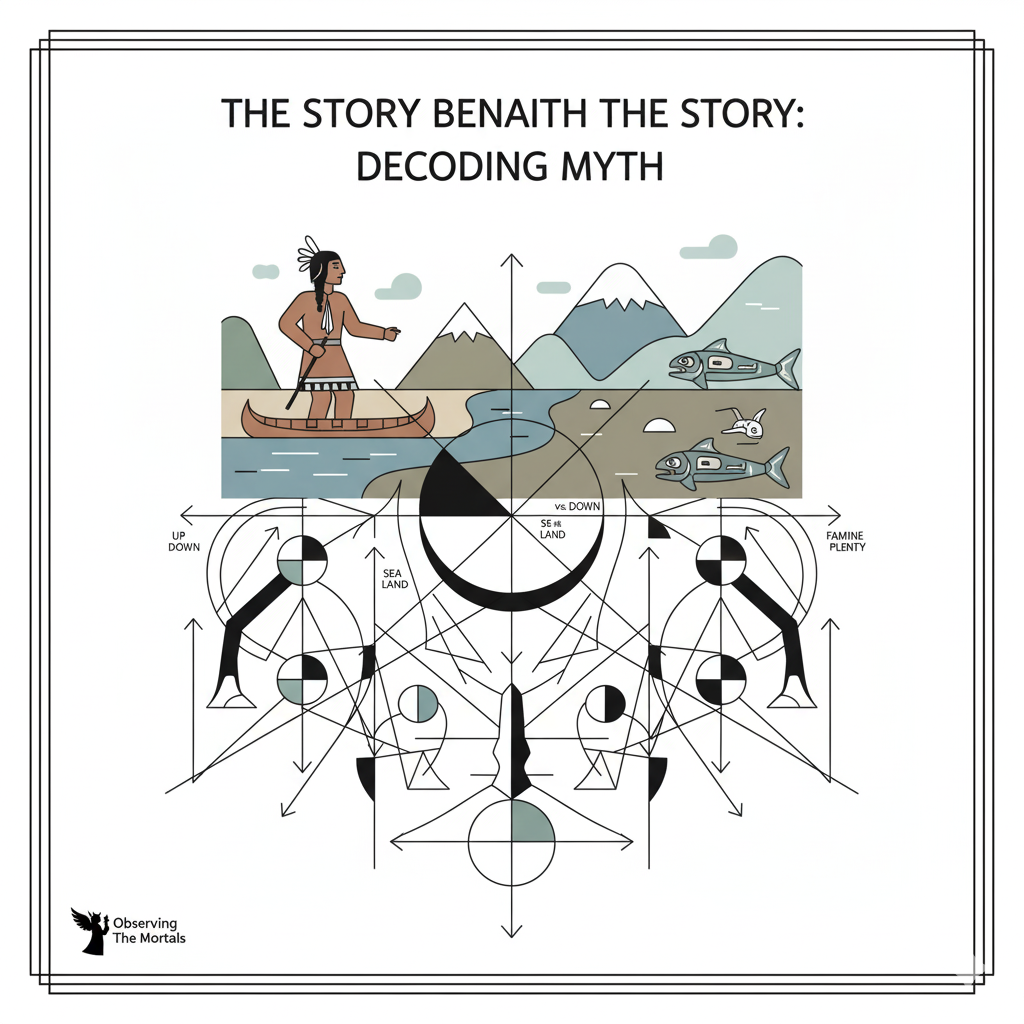

- The Structuralist Method: Decoding the Myth: To find this hidden structure, Lévi-Strauss “broke” the story of Asdiwal into its constituent parts and analyzed them on different levels or “codes.” He showed that each code was organized around a binary opposition:

- Geographic Code: The hero, Asdiwal, constantly moves between opposite locations: upriver vs. downriver, and mountains vs. sea.

- Economic Code: The story contrasts opposite states of being: famine (associated with mountain hunting) vs. plenty (associated with sea fishing).

- Sociological Code: Asdiwal’s marriages create a conflict between two opposing kinship rules: marrying within his own patrilineal group versus marrying into his wife’s matrilineal group.

- Cosmological Code: The entire myth is structured around universal oppositions like high vs. low, life vs. death, and nature vs. culture.

- Mediating the Contradiction: Lévi-Strauss brilliantly demonstrated that the entire narrative of Asdiwal’s journey is an attempt to logically mediate these oppositions. The hero’s movements and actions provide a story-based “solution” to the real-world tensions faced by the Tsimshian (e.g., the conflict between patrilineal and matrilineal descent). The myth doesn’t solve the problem in reality, but it provides a satisfying logical framework for the mind to think through it.

The Anthropologist’s Gaze: A Critical Perspective

Lévi-Strauss’s structuralism, while revolutionary, has been subject to significant criticism.

- Ignoring Content and Context: The most powerful critique is that in its relentless search for universal, underlying structures (the “syntax” of myth), the structuralist method often ignores the rich cultural content, emotional power, and specific historical context of the story (the “semantics”). Is the hidden structure really more important than what the story means to the Tsimshian people who tell it?

- Is the Structure Real or Invented?: Critics have often asked whether the complex binary codes that Lévi-Strauss “discovered” are truly inherent in the myth, or if they are a product of his own brilliant, pattern-seeking mind. The approach can be seen as overly intellectual and unfalsifiable—it’s hard to prove his interpretation wrong.

- Downplaying Human Agency: By focusing on impersonal, universal mental structures, the model can be seen as downplaying the role of human agency, creativity, and emotion in the creation and telling of myths.

The Exam Angle: How to Use This in Your Mains Answer

- Types of Questions Where It can be used:

- “Critically evaluate the contributions of the structuralist school of thought in anthropology.”

- “What is the anthropological significance of myth? Explain with examples.”

- “Discuss the key theoretical contributions of Claude Lévi-Strauss.”

- Model Integration:

- To define Structuralism: “Structuralism, pioneered by Claude Lévi-Strauss, seeks to uncover the universal, underlying binary structures of human thought. His analysis of ‘The Story of Asdiwal’ is a classic demonstration, where he deconstructed a myth into different codes—geographic, economic, sociological—to reveal its function as a logical tool for mediating cultural contradictions.”

- On the Study of Myth: “For Lévi-Strauss, a myth is not a simple narrative but a complex structure of binary oppositions. In his analysis of the Asdiwal myth, he showed how oppositions like ‘land vs. sea’ or ‘patriliny vs. matriliny’ are used by a society to think through and logically resolve its most fundamental social tensions.”

- To offer a critique: “While Lévi-Strauss’s structuralist method was revolutionary, it has been critiqued for being overly formalistic. Critics argue that in his search for universal binary oppositions in myths like ‘The Story of Asdiwal,’ he often ignored the specific cultural context, historical background, and emotional meaning of the story for the people who tell it.”

Observer’s Take

Lévi-Strauss’s analysis of a single Tsimshian folk tale is one of the most intellectually ambitious projects in all of anthropology. It’s akin to a physicist trying to discover the Grand Unified Theory by studying a single atom. He taught us to look at stories not as simple entertainment or flawed science, but as the incredibly sophisticated logical instruments that human societies use to make sense of a contradictory and often messy world. While his methods remain debated, his core insight is profound: beneath the chaotic and diverse surface of human culture may lie deep, elegant structures of thought. The key to understanding humanity, he proposed, is to learn how to read the unconscious logic of the stories we tell ourselves.