What is the ultimate foundation of the Indian caste system? Is it a system of economic exploitation, a structure of political power, or something else entirely? In 1966, the brilliant French anthropologist Louis Dumont published a monumental work that offered a radical and provocative answer. He argued that to understand caste, Westerners and modern Indians alike had to first shed their own values of equality and individualism. The true logic of the system, he contended, was not about power or wealth, but about a unique and all-encompassing religious ideology: the opposition of purity and pollution. This case study delves into his classic and deeply contested theory.

The Information Box

Syllabus Connection:

- Paper 2: Chapter 3 (Caste System: Features, Structure, Theories of Origin), Chapter 4 (Religion and Society)

- Paper 1: Chapter 6 (Anthropological Theories: Structuralism), Chapter 2.5 (Social Stratification)

Key Concepts/Tags:

- Homo Hierarchicus, Louis Dumont, Purity and Pollution, Status vs. Power, Caste System, Structuralism

The Setting: Who, What, Where?

This is the world of Louis Dumont, a highly influential French sociologist and Indologist. His grand theory is laid out in his 1966 masterpiece, Homo Hierarchicus: The Caste System and Its Implications. This is not a traditional village ethnography but a sweeping structuralist analysis that synthesizes classical Sanskrit texts (like the Dharmashastras) with existing ethnographic data to build a single, coherent model of the caste system as a pan-Indian ideological structure.

The Core Argument: Why This Study Matters

Dumont’s work was revolutionary because he insisted on analyzing the caste system on its own terms, not through a Western lens.

- Homo Hierarchicus vs. Homo Aequalis: Dumont’s starting point was a fundamental distinction. He argued that modern Western society is built on the ideal of the individual and equality (Homo Aequalis). Indian society, in contrast, is traditionally built on the principle of the group and hierarchy (Homo Hierarchicus). To judge one by the standards of the other is to fundamentally misunderstand it.

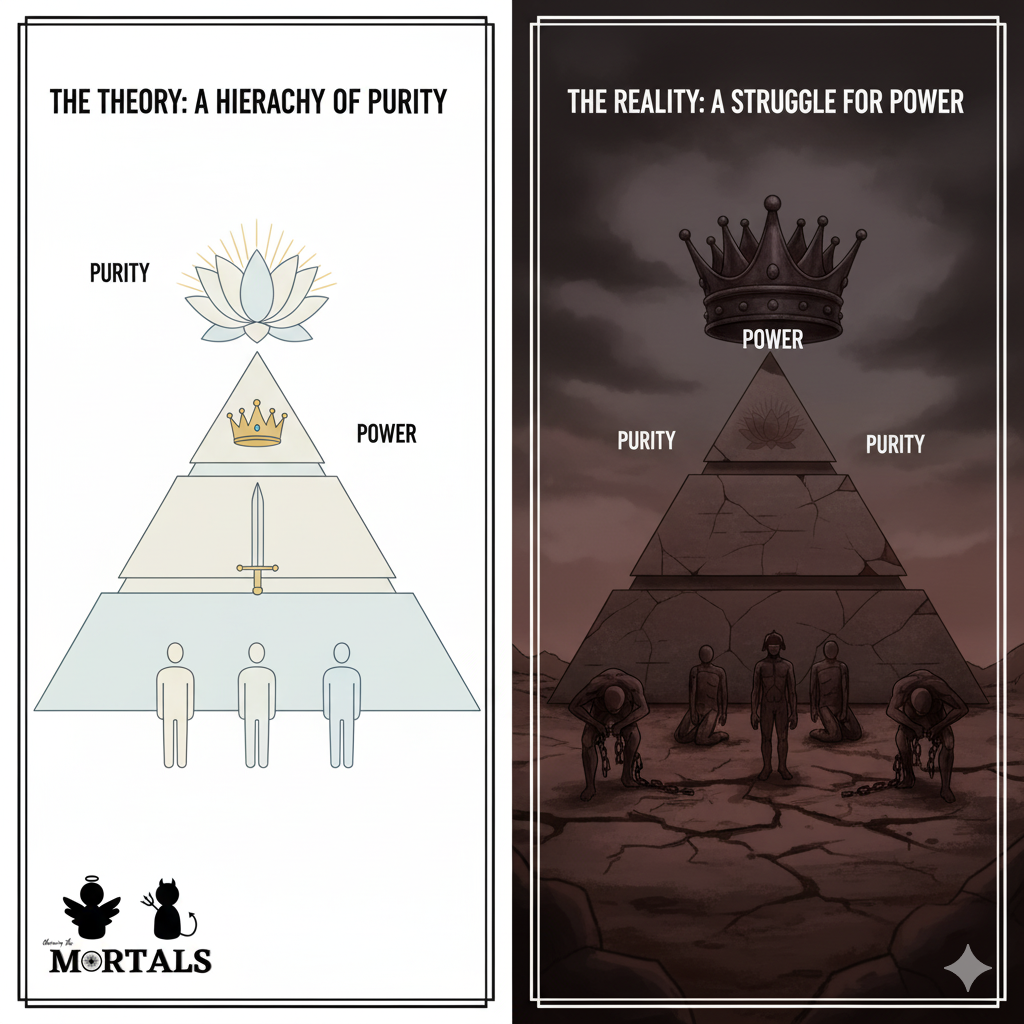

- The Primacy of Religious Ideology: Dumont’s most powerful claim is that the caste hierarchy is not based on power or economics, but on a single, overarching religious ideology: the binary opposition of purity and pollution. A group’s rank in the hierarchy is determined by its relative degree of ritual purity. The Brahmin is at the top not because he is the most powerful, but because he is ritually the most pure. The Dalit (“Untouchable”) is at the bottom because their traditional occupations involve dealing with the most polluting substances (death, waste).

- The Separation of Status and Power: From this central principle flows a crucial insight. Dumont argued that in the pure, traditional model of the caste system, ultimate status (ritual purity) and ultimate power (temporal/political authority) are fundamentally separated. The Brahmin holds the highest status, but he is spiritually and ritually superior to the Kshatriya king, who holds the actual political and military power. This disjunction of ritual status and real-world power, he argued, is the unique structural genius of the caste system.

- The Principle of Encompassment: The entire system is held together because the principle of purity “encompasses” the principle of power. This means that while the king may have power, his power is ultimately considered legitimate only within the larger religious and moral order defined by the Brahmin and the ideology of purity.

The Anthropologist’s Gaze: A Critical Perspective

Dumont’s elegant model has been the subject of intense debate and criticism.

- A “Brahminical” View of Caste?: The most significant critique, leveled by anthropologists like Gerald Berreman, is that Dumont’s model is based too heavily on classical upper-caste texts and presents an idealized, “Brahminical” view of the system. It focuses on ideology and religious consensus, while largely ignoring the brutal, lived reality of oppression, economic exploitation, and violent conflict that defines the system for those at the bottom.

- Ignoring the Role of Power: Materialist and subaltern scholars have strongly challenged the separation of status and power. They argue that this is a false dichotomy and that ritual status is, in fact, deeply intertwined with and often serves as a direct justification for the material and political dominance of the upper castes.

- A Static and Ahistorical Model?: By focusing on a timeless, pan-Indian ideological structure, Dumont’s model is often criticized for being ahistorical. It does not adequately account for the immense regional variations in the caste system, nor for the profound changes it has undergone due to historical events, colonial rule, and modern politics.

The Exam Angle: How to Use This in Your Mains Answer

- Types of Questions Where It can be Used:

- “Critically evaluate the various theories on the origin and structure of the caste system.”

- “What is the relationship between caste and religion in the Indian social system?”

- “Discuss the key contributions of Louis Dumont to the study of Indian society.”

- Model Integration:

- To explain the ideology of caste: “Louis Dumont, in his structuralist work ‘Homo Hierarchicus,’ argued that the fundamental principle of the caste system is not power but a religious ideology based on the binary opposition of purity and pollution, which dictates the entire social hierarchy.”

- For a nuanced view: “A key insight from Louis Dumont’s analysis of caste is his concept of the separation of ritual status and temporal power. He argued that the Brahmin, who holds the highest status, is traditionally subordinate in the political domain to the Kshatriya king, a structure he saw as unique to Indian hierarchy.”

- To offer a critique: “While Dumont’s ‘Homo Hierarchicus’ is a foundational text, it has been heavily critiqued for presenting an idealized, Brahminical view of caste. Scholars like Gerald Berreman argue that it over-emphasizes religious ideology while downplaying the lived reality of oppression, conflict, and power relations that define the system for lower castes.”

Observer’s Take

Homo Hierarchicus is one of the most intellectually ambitious and consequential books ever written on Indian society. Its genius was to take the seemingly chaotic and infinitely complex reality of caste and propose a single, elegant, underlying logic for it all. Dumont forced the world to take the ideology of caste seriously, not just as a flimsy justification for power, but as a powerful and coherent system of thought in its own right. While his model has been fiercely debated and challenged, it remains the essential starting point for any deep anthropological discussion of caste. To begin to understand the complexities of modern India, one must first grapple with Dumont’s powerful and unsettling portrait of Homo Hierarchicus.