Think about a major life transition: a wedding, a graduation ceremony, or even the intense experience of basic military training. There’s often a phase where you are “betwixt and between”—no longer what you were, but not yet what you are about to become. The British cultural anthropologist Victor Turner argued that this “in-between” stage is not just a brief, awkward pause. He saw it as one of the most sacred, creative, and powerful spaces in all of human social life. This case study delves into his foundational concepts of Liminality and Communitas, which provide a powerful lens for understanding why rituals are so transformative.

The Information Box

Syllabus Connection:

- Paper 1: Chapter 5 (Anthropology of Religion: Myth and Ritual), Chapter 6 (Anthropological Theories: Manchester School), Chapter 2.5 (Socialization: Rites of Passage)

Key Concepts/Tags:

- Victor Turner, Liminality, Communitas, Rite of Passage, Ndembu, Ritual Process

The Setting: Who, What, Where?

This is the intellectual world of Victor Turner, a leading figure in the Manchester School of anthropology, renowned for his focus on social processes, conflict, and symbolism. His most influential ideas are detailed in books like The Forest of Symbols (1967) and The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure (1969). Turner’s theories are not just abstract; they are deeply grounded in his long-term ethnographic fieldwork among the Ndembu people of northwestern Zambia in the 1950s.

The Core Argument: Why This Study Matters

Turner’s genius was to take the existing three-stage model of “rites of passage” (formulated by Arnold van Gennep) and conduct a deep, microscopic analysis of the crucial middle phase.

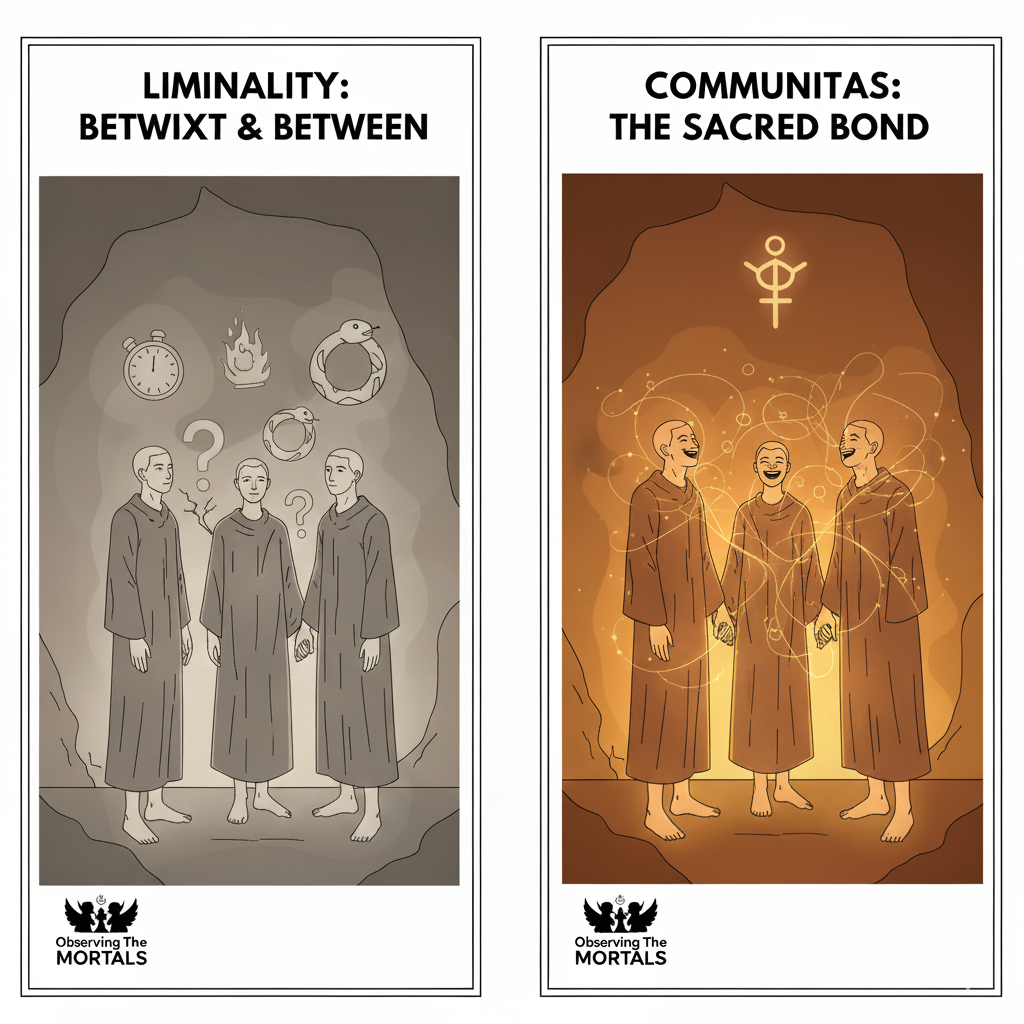

- “Liminality”: The State of “Betwixt and Between”: Turner used the term liminality (from the Latin limen, meaning “threshold”) to describe the second stage of a rite of passage. It is a state of profound ambiguity and disorientation. The person in this phase (the “liminar”) is stripped of their old social status and identity but has not yet been granted their new one. They are structurally “invisible”—often treated as if they are dead, in a womb, or sexless. This phase is characterized by symbols of paradox, as initiates are often secluded, dressed alike, and stripped of all personal property.

- “Communitas”: The Deep Bond of the Threshold: This is Turner’s most famous and powerful concept. He argued that within the structureless, chaotic void of liminality, a unique and intense social bond emerges: communitas. It is a feeling of direct, immediate, and egalitarian comradeship among the group of initiates. All the usual markers of social structure—hierarchy, status, wealth, and property—are temporarily dissolved. What remains is a profound sense of shared humanity. Communitas is the opposite of “society” (which is structured and hierarchical); it is an experience of “anti-structure.”

- The Ndembu Example (mukanda): Turner’s ideas were shaped by his study of Ndembu initiation rituals like the mukanda for boys. In this rite, young boys are separated from their mothers and the village. They are taken to a secluded camp in the forest (a classic liminal space), where they are circumcised, taught tribal lore, and subjected to ordeals together. In this shared vulnerability, they form an intense, lifelong bond of communitas. Finally, they are reincorporated back into the village, no longer as boys, but as men with a new social status.

The Anthropologist’s Gaze: A Critical Perspective

- Is “Communitas” Always a Positive Experience?: Turner’s description of communitas is often beautiful and positive, emphasizing spontaneity and human connection. A critical perspective, however, would ask if this is a romanticized view. The liminal phase can also be a terrifying and traumatic experience filled with hazing, abuse, and forced conformity. The bond that emerges might be one of shared trauma rather than pure, egalitarian comradeship.

- Overlooking Gender and Power: Turner’s classic examples, like the mukanda, often focus on male rituals. Feminist anthropologists have questioned how these concepts apply to women’s rites, which may have very different dynamics and outcomes. Does the experience of “anti-structure” feel the same for the less powerful members of a society as it does for those who are already powerful?

- Applicability to Modern Life: While Turner himself applied these concepts to modern phenomena like hippie movements and religious pilgrimages, a critique would question how well a model derived from a small-scale, face-to-face tribal society can explain the complex and often fleeting experiences of transitions in large-scale, anonymous modern societies.

The Exam Angle: How to Use This in Your Mains Answer

- Types of Questions Where It can be Used:

- “What is a rite of passage? Analyze its structure and function with ethnographic examples.”

- “Critically evaluate the key contributions of the Manchester School in anthropology.”

- “Discuss the anthropological significance of ritual.”

- Model Integration:

- On Ritual: “Victor Turner’s analysis of the ritual process went beyond a simple functionalist view. His concept of ‘liminality’ describes the ambiguous ‘in-between’ phase of a rite of passage, where social structures are suspended, as he observed in the Ndembu initiation rites.”

- On Communitas: “A key contribution of Victor Turner to the study of religion is the concept of ‘communitas.’ He argued that during the liminal phase of a ritual, participants experience a profound, egalitarian bond—a form of ‘anti-structure’ that temporarily dissolves social hierarchy and creates a deep sense of shared humanity.”

- To offer a critique: “While Victor Turner’s concept of communitas is powerful, it has been critiqued for potentially romanticizing the ritual experience. Critics argue that the liminal phase can also be a site of trauma and coercion, and that the model may not fully account for the dynamics of gender and power within the ritual process.”

Observer’s Take

Victor Turner gave us the vocabulary to understand one of the most magical and transformative aspects of human social life. He showed us that the moments when we feel most lost, most disoriented, and most “in-between” are also the moments of greatest potential—for personal change, for spiritual growth, and for forging the deepest possible human connections. His work on liminality and communitas is a profound reminder that human societies need both structure and its opposite to be whole. We need the reliable order of our everyday lives, but we also desperately need those sacred, chaotic, liminal spaces where the rules fall away and we can remember what it feels like to just be human, together.