For centuries, the Mahua flower has been at the heart of tribal life in Central India. It is a sacred tree, a vital source of food, and the base for a traditional brew that is integral to every ritual and celebration. This brew, often made in the shadows and deemed “unauthorised,” is now stepping into the light. The Maharashtra government has launched a radical new policy to legalize and formalize the production of Mahua liquor, aiming to turn this traditional spirit into a branded, export-quality “heritage” product. This case study explores this delicate and ambitious experiment: a balancing act between respecting culture, empowering women, and navigating the potent risks of commercialization.

The Information Box

Syllabus Connection:

- Paper 2: Chapter 6.1 (Problems of Tribal Communities), Chapter 6.2 (Tribal Administration), Chapter 7 (Role of Anthropology in Tribal Development)

- Paper 1: Chapter 3 (Economic Anthropology: Market Integration), Chapter 9 (Applied Anthropology)

Key Concepts/Tags:

- Mahua, Non-Timber Forest Product (NTFP), Women’s SHGs, Applied Anthropology, Commodification of Culture, Tribal Economy

The Setting: Who, What, Where?

The setting is the Satpura mountain range in Maharashtra, home to several tribal communities. The core of the case study is a new state government policy designed to institutionalize the production and sale of liquor from Mahua flowers. A key feature of this initiative is its implementation model: the entire process, from flower collection to distillation and marketing, is being driven by tribal women’s Self-Help Groups (SHGs), with a pilot project already underway in the Nashik region. The state’s Tribal Development Department is providing financial and technical support.

The Core Argument: Why This Study Matters

This policy is not just about legalizing a local liquor; it is a multi-faceted development model that represents a significant shift in the state’s approach to tribal livelihoods.

- Formalizing the Informal Tribal Economy: The most significant change is the legal recognition of a traditional skill. By bringing the production of Mahua liquor into the formal economy, the policy aims to de-criminalize a traditional practice and create a legitimate, taxable source of income. This is a move from suppression to promotion.

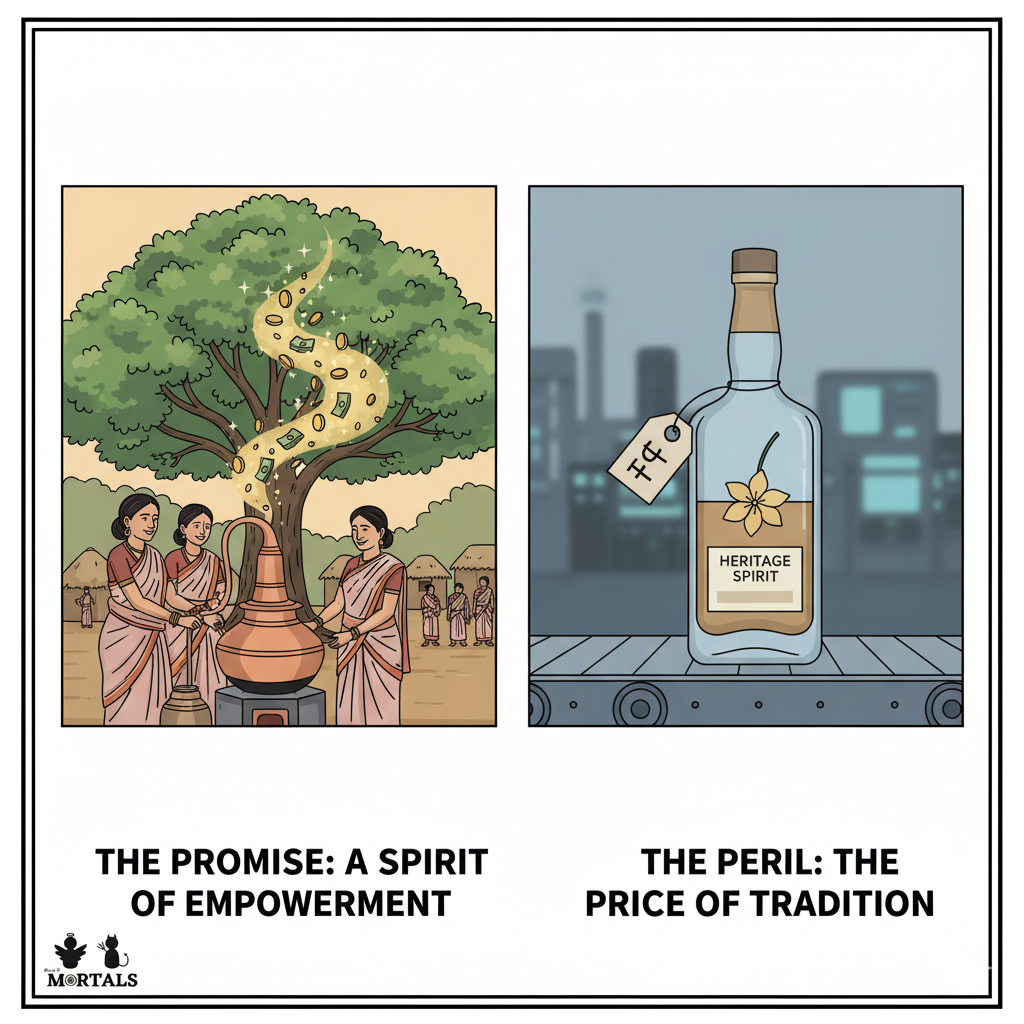

- A Women-Centric Development Model: The policy is explicitly designed for women’s empowerment. By placing the entire value chain in the hands of women’s SHGs, it aims to ensure that the economic benefits flow directly to the women who have traditionally been the primary collectors of Mahua flowers, giving them greater financial autonomy and decision-making power.

- Value Addition and Eliminating Middlemen: This model moves beyond the simple sale of a raw Non-Timber Forest Product (NTFP). It encourages value addition (turning flowers into a high-value branded liquor) and aims to connect the producers directly to lucrative urban and export markets. This is a direct strategy to bypass the exploitative middlemen who typically purchase raw Mahua flowers from tribal collectors at very low prices.

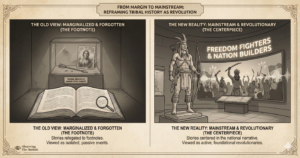

- Branding “Heritage” for a Modern Market: The plan to market Mahua liquor as a “tribal heritage product” is a savvy economic strategy. It leverages the cultural authenticity, indigenous knowledge, and unique story behind the product as its Unique Selling Proposition (USP), tapping into a growing global market for artisanal and craft spirits.

The Anthropologist’s Gaze: A Critical Perspective

An anthropological lens reveals the deep complexities and potential risks beneath this promising policy.

- The “Commodification of the Sacred”: An anthropologist would critically analyze this as the commodification of a ritual substance. In many tribal communities, Mahua liquor is not just an intoxicant; it is used in offerings to deities, shared to seal social bonds, and is integral to festivals and life-cycle ceremonies. What happens to this sacred and social meaning when the brew is bottled, given a price tag, and sold for profit in a metropolitan bar? There is a profound risk of stripping the product of its cultural soul.

- The Risk of Over-Exploitation: While the policy aims for a sustainable livelihood, a surge in commercial demand could lead to the over-harvesting of Mahua flowers. This could have negative ecological consequences and could also impact the local community’s food security, as the flowers are also an important source of nutrition.

- Unintended Social Consequences: The shift from small-scale, local consumption to large-scale, profit-driven production could have unforeseen social impacts. The article rightly notes the “possibility of alcohol abuse.” An anthropological study would be needed to monitor whether the increased availability and commercialization of liquor changes local consumption patterns and social norms around drinking.

- Empowerment or New Dependency?: The SHG model is designed for empowerment, but a critical observer would look at the long-term power dynamics. Will the women’s SHGs become truly independent entrepreneurs? Or will they become perpetually dependent on the Tribal Development Department for funding, technical know-how, and market access, creating a new form of bureaucratic control that replaces the old middlemen?

The Exam Angle: How to Use This in Your Mains Answer

- Types of Questions Where It can be Used:

- “Discuss the role of Non-Timber Forest Products (NTFPs) in the tribal economy.”

- “Analyze the impact of market integration on the culture and livelihoods of tribal communities.”

- “Women’s SHGs are key to tribal development. Critically evaluate.”

- Model Integration:

- On Tribal Economy (Paper 2): “Recent state policies are attempting to integrate the tribal economy with the mainstream by formalizing traditional skills. For example, the Maharashtra government’s Mahua policy legalizes the production of traditional liquor by tribal women’s SHGs, aiming to create a value-added ‘heritage product’ from a key Non-Timber Forest Product.”

- On Women’s Empowerment: “Women’s SHGs are increasingly being used as a vehicle for tribal development. Maharashtra’s Mahua liquor policy is a case in point, where the entire value chain, from flower collection to production, is deliberately placed in the hands of women, aiming to ensure that economic benefits directly empower them.”

- To offer a critique (Applied Anthro): “While policies like Maharashtra’s Mahua initiative are celebrated for their economic potential, an anthropological perspective would caution against the ‘commodification of the sacred.’ The central challenge is to balance the commercialization of a traditional product with the preservation of its cultural and ritual significance within the community.”

Observer’s Take

The Maharashtra Mahua policy is a bold and fascinating experiment in applied anthropology. It is an attempt to weave together the often-competing threads of economic empowerment, women’s leadership, cultural respect, and market savvy. On the one hand, it holds the incredible promise of transforming a marginalized community’s traditional knowledge into a source of sustainable wealth and global recognition. On the other, it walks a perilous tightrope over the risks of commercial exploitation, ecological damage, and the potential dilution of a sacred tradition. The success of this initiative will ultimately depend on whether it can truly keep the power, the profits, and the narrative in the hands of the tribal women who have been the stewards of the Mahua tree for centuries. It’s a critical test of whether a sacred spirit can find its place in the modern market without losing its soul.