What if you could unlock the secrets of your deep past, trace your ancestors’ migrations across continents, and discover your “true” ethnic makeup, all with a simple vial of saliva? This is the seductive promise of direct-to-consumer DNA ancestry tests, a booming global industry that is now making significant inroads in India. But in a country with a uniquely complex and layered history of migrations, caste endogamy, and diverse communities, what do these seemingly objective scientific tests really tell us? This case study explores the rise of genetic ancestry testing in India and asks a critical anthropological question: is this a harmless tool for self-discovery, or is it a new, scientific way of creating, and complicating, social divisions?

The Information Box

Syllabus Connection:

- Paper 1: Chapter 9.4 (Human DNA profiling), Chapter 1.6 (Race and Racism), Chapter 12 (New perspectives in Anthropology: Medical Anthropology)

- Paper 2: Chapter 2.0 (Demographic Profile of India), Chapter 3 (Caste System)

Key Concepts/Tags:

- DNA Ancestry Testing, Genetic Ancestry, Social Identity, Race as a Social Construct, Medical Anthropology, Biopower

The Setting: Who, What, Where?

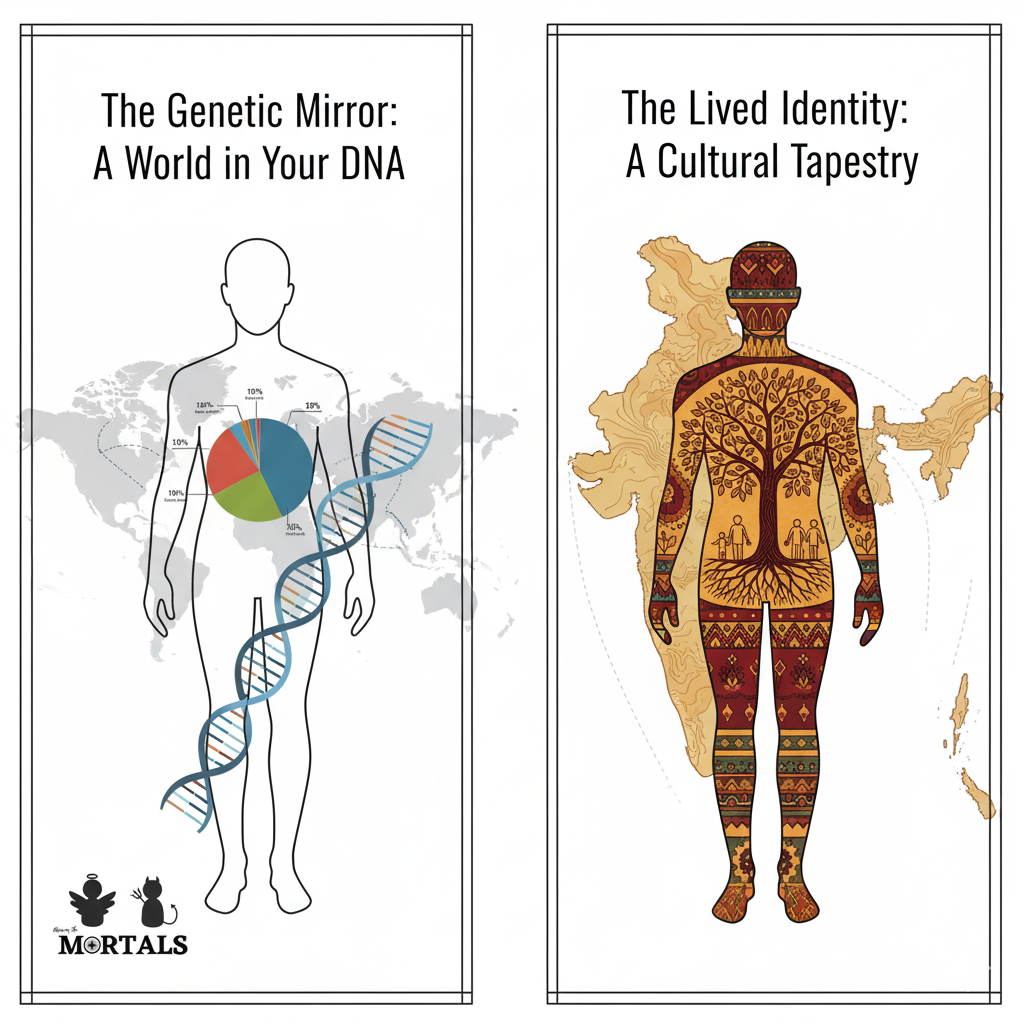

The phenomenon is the growing popularity of Direct-to-Consumer (DTC) DNA ancestry tests from global companies like AncestryDNA, 23andMe, and MyHeritage within the Indian market, particularly among the urban middle class and the diaspora. The technology involves analyzing an individual’s saliva to compare their unique DNA markers against the company’s vast reference databases. The result is a percentage-based breakdown of one’s supposed “ethnic” or “ancestral” origins, often presented on a colorful world map.

The Core Argument: Why This Study Matters

This is a critical case study on the collision of modern genetic science with deeply rooted social identities.

- The Allure of Scientific “Truth”: The primary appeal of these tests lies in their promise of an objective, scientific, and seemingly unbiased answer to the deeply personal question, “Where do I come from?” In a society like India, where family histories can be fragmented and identities are often contested, the certitude of a simple percentage breakdown (“40% South Indian,” “15% Central Asian”) is incredibly powerful.

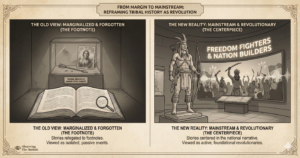

- Reinforcing vs. Disrupting Narratives: The results of these tests have a profound, and often unpredictable, impact on personal and family identities.

- They can reinforce existing oral histories or community identities (e.g., confirming a long-held family story of Persian ancestry).

- Conversely, they can dramatically disrupt established narratives. Discovering unexpected ancestral links can challenge deeply held notions of regional identity, lineage, and even caste “purity,” sometimes causing confusion or conflict within families.

- The Medicalization of Identity: Many of these services, like 23andMe, bundle ancestry reports with health and wellness reports based on genetic markers. This contributes to a broader trend of the medicalization of identity, where who you are, your heritage, and your future are increasingly understood through a bio-medical and genetic lens, linking your ancestry to specific health risks and predispositions.

The Anthropologist’s Gaze: A Critical Perspective

An anthropological analysis moves beyond the marketing claims to reveal the deep complexities and potential pitfalls of this technology.

- Genetic Ancestry is Not Cultural Identity: This is the most crucial anthropological critique. These tests provide a statistical probability of genetic ancestry, not a measure of cultural identity or kinship. Your DNA might show 10% “Irish” ancestry, but this scientific abstraction has no bearing on your lived reality as an Indian who does not speak the language, know the culture, or have any social connection to Ireland. The tests can create a dangerous confusion between a biological trace and a social reality.

- The Problem of “Race as a Social Construct”: These tests present ancestry in neat, geographically-bound, and often racialized categories (“East Asian,” “European,” “Sub-Saharan African”). An anthropologist would argue that this can inadvertently reify—or make real again—the idea of race as a biological fact. It risks undoing decades of anthropological work showing that race and ethnicity are fluid social constructs, not fixed genetic categories.

- The Bias in the Database: The accuracy and granularity of the results depend entirely on the reference populations in the company’s database. These databases have historically been, and largely remain, heavily skewed towards people of European descent. This means the results for under-represented populations, including many specific caste and tribal groups in India, can be vague (“Broadly South Asian”) or less reliable.

- Biopower and Genetic Surveillance: From a Foucauldian perspective, the mass collection of human genetic material by a few large multinational corporations represents a new and powerful form of biopower. These companies are building vast, private bio-banks, the future uses, privacy, and control of which raise significant ethical and political questions.

The Exam Angle: How to Use This in Your Mains Answer

- Types of Questions Where It can be Used:

- “Critically evaluate the applications and implications of human DNA profiling.”

- “Race is a social construct, but it has a powerful social reality. Discuss.”

- GS-1/3: “Discuss the social and ethical implications of new and emerging technologies.”

- Model Integration:

- On DNA Profiling (Paper 1): “The application of DNA profiling has expanded beyond forensics to popular direct-to-consumer ancestry testing. While intriguing, these tests raise critical anthropological questions about the difference between statistical genetic ancestry and lived cultural identity, and they risk reifying race as a biological category.”

- On Race as a Social Construct: “The social construction of race is paradoxically challenged by the rise of DNA ancestry tests, which present ethnicity as a scientific percentage. An anthropological critique would argue that these tests, while scientifically valid on one level, can mislead users into believing that fluid social identities can be reduced to simple, biologically determined categories.”

- For a GS/Essay Answer: “New technologies like DNA ancestry testing have profound social implications. While offering a sense of personal discovery, they also raise major ethical issues of data privacy and can complicate, or even disrupt, traditional notions of identity, kinship, and community in a society as diverse as India.”

Observer’s Take

The quest to know “who we are” is a fundamental human drive. DNA ancestry tests have packaged this profound quest into a simple, affordable, and scientifically alluring product. But as we send off our saliva samples, we must ask what we are truly searching for. An anthropological perspective is a crucial reminder that the story these tests tell is only one, partial, and statistically derived chapter of our identity. The richer, more complex, and more meaningful story is written not in our genes alone, but in our kinship, our language, our food, our memories, and our communities. The danger is not in the science itself, but in the temptation to believe that a percentage on a screen can ever fully capture the profound and messy reality of what it means to be human.