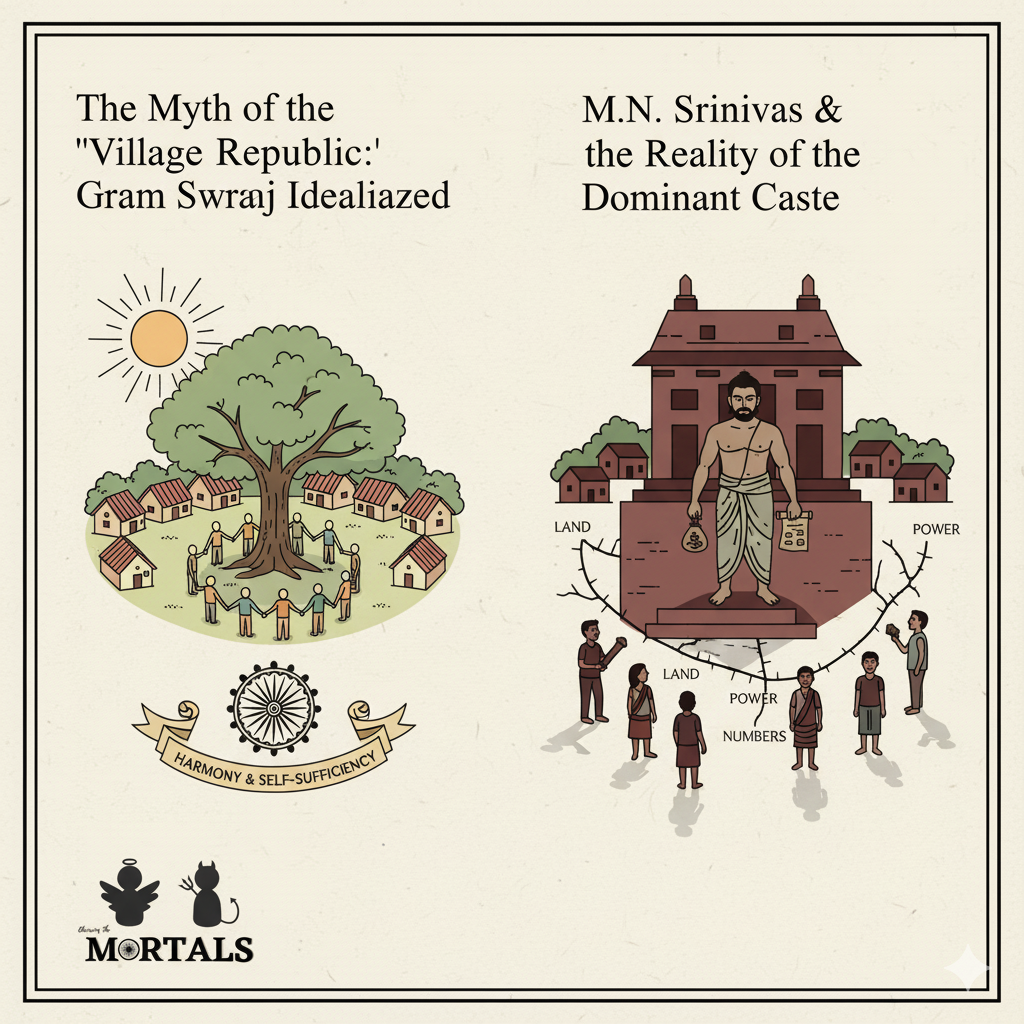

On Gandhi Jayanti, it is common to remember Mahatma Gandhi’s vision of the Indian village as a harmonious, self-sufficient “little republic” or Gram Swaraj. It’s a powerful and beautiful ideal. However, in the years after Independence, the pioneering Indian sociologist and anthropologist M.N. Srinivas, through deep, on-the-ground fieldwork, painted a much more complex and challenging picture. He revealed that the village was not a community of equals, but a deeply stratified arena of power. This case study explores his powerful analytical tool for understanding this reality: the concept of the “Dominant Caste.”

The Information Box

Syllabus Connection:

- Paper 2: Chapter 3.3 (Caste System), Chapter 5.2 (Indian Village: Power Structure), Chapter 9.2 (Backward Class Movements)

- Paper 1: Chapter 4 (Political Anthropology: Power, Authority, Leadership)

Key Concepts/Tags:

- Dominant Caste, M.N. Srinivas, Indian Village Studies, Power Structure, Sanskritization, Gram Swaraj

The Setting: Who, What, Where?

This is the world of M.N. Srinivas, one of the most important figures in the history of Indian Sociology and Social Anthropology. His concept of the Dominant Caste emerged from his intensive ethnographic fieldwork in the village of Rampura (a pseudonym) near Mysore in Karnataka during the late 1940s. His insights, detailed in his famous essays and his classic book The Remembered Village (1976), moved the study of Indian society from a reliance on ancient texts (the “book view”) to a focus on the lived reality of the village (the “field view”).

The Core Argument: Why This Study Matters

Srinivas’s concept provided a revolutionary new framework for understanding the actual distribution of power in rural India, challenging both the textual and the romanticized views of the village.

- Challenging the Brahmin-centric “Book View”: Before Srinivas, the caste system was often understood simply in terms of the ritual hierarchy described in sacred texts, with the Brahmin at the apex. Srinivas’s fieldwork showed that the ritually highest caste was not always the most powerful in secular, day-to-day matters.

- Defining the “Dominant Caste”: He argued that a caste could be considered “dominant” when it possessed a combination of several crucial attributes. A single attribute was not enough. The key criteria were:

- Numerical Strength: The caste should be the largest in number in the village or local area.

- Economic Power: Crucially, it must own a significant portion of the arable land. In an agrarian society, land is the primary source of power.

- Political Power: It has a strong representation and influence in local decision-making bodies and has connections to the wider state political machinery.

- Relatively High Ritual Status: While not necessarily Brahmin, it should have a high (though not necessarily the highest) position in the local caste hierarchy.

- Western education and government jobs were also emerging as new sources of dominance.

- Power in Action: The Dominant Caste in a village (the Okkaligas in Rampura, for example) functioned as the effective ruling group. They were the main landlords, employers, and moneylenders. They settled disputes, effectively acting as the village court. They were also the main reference group for lower castes seeking upward social mobility (a process Srinivas famously called Sanskritization).

The Anthropologist’s Gaze: A Critical Perspective

While foundational, the concept of the Dominant Caste has been subject to critical re-evaluation over time.

- Is it Still Relevant Today?: The most important critical question is the concept’s relevance in the 21st century. Has the consolidated power of traditional dominant castes been weakened by decades of land reforms, the Green Revolution (which economically empowered other middle castes), the rise of Dalit political consciousness (Bahujan politics), and reservations for women and lower castes in Panchayati Raj?

- From Single Caste to “Dominant Bloc”: Many contemporary scholars argue that power in many villages is no longer held by a single dominant caste. Instead, politics operates through fluid, multi-caste alliances that come together to form a temporary “dominant bloc” to capture power, especially in local elections.

- A Universal Model for India?: Srinivas developed the model from his intensive study of a single village in multi-caste South India. A critical perspective would question how well this model applies to other regions of India with different historical, agrarian, and caste configurations, such as areas with a greater tribal population or different land tenure systems.

The Exam Angle: How to Use This in Your Mains Answer

- Types of Questions Where It can be Used:

- “Analyze the power structure of the Indian village.”

- “Critically evaluate the concept of the ‘Dominant Caste’ in the context of contemporary social changes.”

- “Discuss the contributions of M.N. Srinivas to the study of Indian society.”

- Model Integration:

- To define the concept: “M.N. Srinivas’s concept of the ‘Dominant Caste,’ developed from his study of Rampura village, provided a realistic model of rural power. He argued that dominance is a composite of numerical strength, economic power (especially land ownership), and political influence, not just ritual status.”

- For a critical view on the Indian Village: “Challenging the romanticized Gandhian ideal of the harmonious ‘village republic,’ Srinivas’s ethnographic work revealed the Indian village as a site of entrenched hierarchy and conflict, where a ‘Dominant Caste’ often controls the economic and political life of the entire community.”

- To discuss changing power dynamics: “While the concept of a single ‘Dominant Caste’ was foundational for understanding the post-Independence village, its relevance is now debated. The rise of Dalit political parties and reservations in Panchayats have challenged traditional hierarchies, leading in many areas to more fluid, multi-caste power alliances rather than the hegemony of a single group.”

Observer’s Take

M.N. Srinivas’s work was not a rejection of the ideal of Gram Swaraj, but a brutally honest, on-the-ground diagnosis of the reality that stood in its way. He showed that true self-governance and village harmony could never be achieved without first confronting the deeply entrenched power structures of caste and land ownership. On this day, as we reflect on Gandhi’s vision, Srinivas’s concept of the “Dominant Caste” remains a powerful and necessary analytical tool. It reminds us that to build the equitable and just village of our dreams, we must first have the courage to honestly observe and understand the unequal village that actually exists.