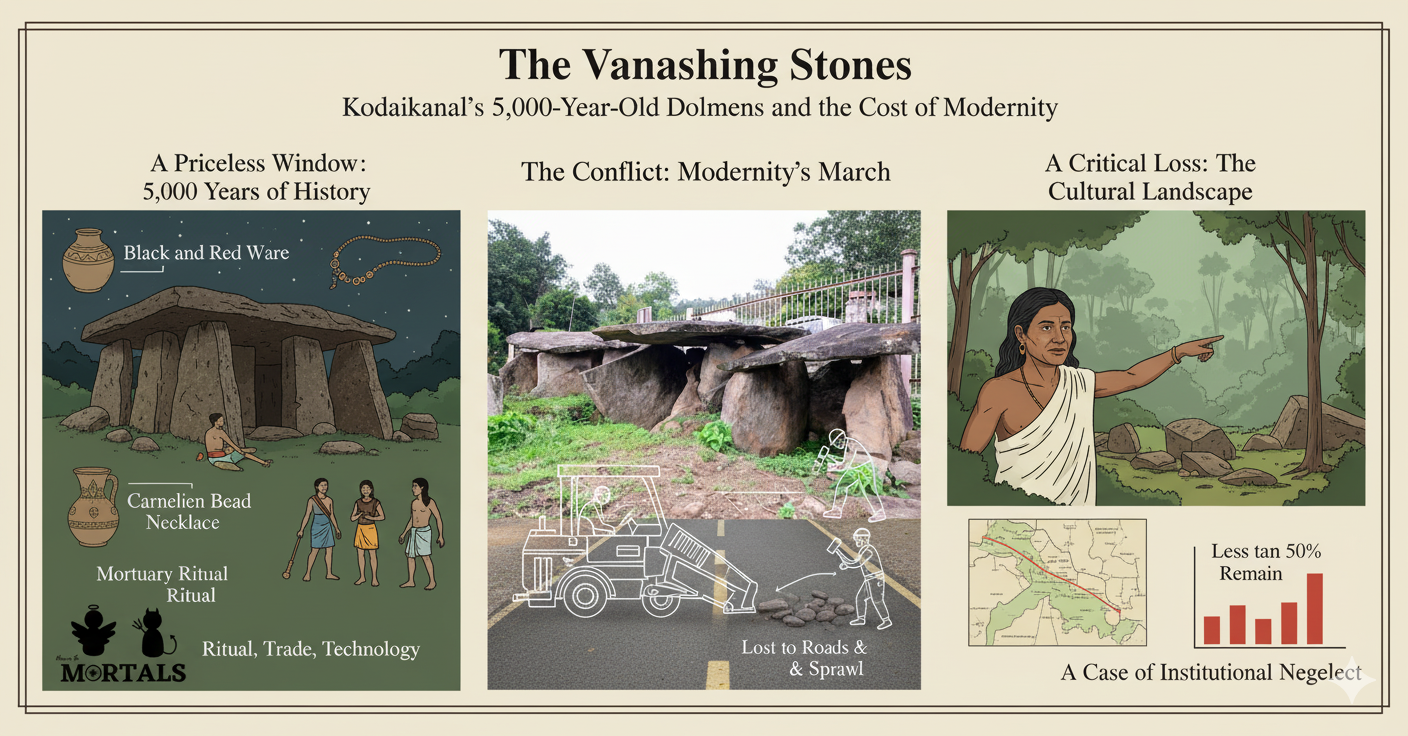

High in the Palani Hills of Tamil Nadu, a silent and ancient story is being erased. For over 5,000 years, megalithic dolmens—stone-slab structures built as homes for the dead—have stood as a testament to the earliest cultures of South India. They are a window into a prehistoric world of ritual, trade, and community. But a century of modernity has proven to be a greater threat than five millennia of nature. Today, these irreplaceable monuments are vanishing at an alarming rate, dismantled for road construction and subsumed by urban sprawl. This case study is about a priceless cultural landscape that is being lost to neglect and unchecked development.

The Information Box

Syllabus Connection:

- Paper 2: Chapter 1.1 (Indian Prehistory: Iron Age, Megalithic Cultures)

- Paper 1: Chapter 1.3 (Archaeological Anthropology), Chapter 1.8 (Cultural Evolution: Iron Age), Chapter 9 (Applied Anthropology: Heritage Management)

Key Concepts/Tags:

- Megalithic Culture, Dolmens, Kodaikanal, Heritage Management, Salvage Archaeology, Paliyar Tribe, Iron Age

The Setting: Who, What, Where?

This case study is centered on the megalithic dolmens of the Palani Hills in Kodaikanal, Tamil Nadu. These structures, dating back over 5,000 years, represent a crucial phase of South Indian prehistory spanning the Pre-Iron and Iron Ages. They were first systematically documented in the early 20th century by Jesuit researchers, with the help of the indigenous Paliyar tribe who have long inhabited this region. The key actors today are the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), which is tasked with their protection, and the forces of modern development—road construction, urban expansion, and agriculture—that threaten their existence.

The Core Argument: Why This Study Matters

This is not just a story about old stones; it is a critical case study on the irreversible destruction of archaeological heritage.

- A Priceless Window into South Indian Prehistory: The dolmens are a primary, and in some cases only, source of information about the prehistoric societies of the region. Their study reveals insights into:

- Mortuary Practices: They represent a complex system of ancestor veneration.

- Technological Skill: The builders quarried and erected massive stone slabs without modern technology.

- Trade and Sophistication: The discovery of artifacts like Black and Red Ware pottery and carnelian beads within these graves indicates long-distance trade networks and a sophisticated material culture.

- The Direct Clash Between Heritage and “Development”: The central conflict is the direct, physical clash between the preservation of this ancient heritage and the pressures of modern expansion. The stark and tragic fact that less than 50% of the dolmens documented a century ago still remain quantifies this destruction. Roads, resorts, and farm walls are literally being built by cannibalizing these 5,000-year-old structures for their stone.

- A Chronic Failure of Heritage Management: The case highlights a systemic failure in effective heritage management. While the ASI has fenced off a few sites, many others are unprotected and deteriorating under vegetation or being actively destroyed. The fact that the warnings issued by researchers in the 1920s about this very destruction are still perfectly valid today points to a century of institutional neglect.

The Anthropologist’s Gaze: A Critical Perspective

- The “Living” Connection (Ethno-archaeology): An anthropologist would immediately focus on the mention of the Paliyar tribe. The study of these dolmens is not just archaeology; it is ethno-archaeology. The oral histories, local names, and traditional knowledge of the Paliyar people, who have lived in this landscape for generations, could provide invaluable insights into the meaning and function of these structures that cannot be gleaned from the stones alone. The destruction of the sites is therefore also an erasure of the Paliyar’s tangible cultural landscape.

- Landscape Archaeology: This case is a perfect example of the importance of landscape archaeology. The dolmens should not be viewed as isolated objects, but as integral parts of a larger ritual and cultural landscape. Their specific placement on ridges, their orientation, and their relationship to ancient settlements, trade routes, and water sources all tell a story. When this landscape is fragmented by modern construction, the entire story is lost, not just the individual monuments.

- The Politics of Heritage: Why are these prehistoric sites so neglected compared to a grand medieval temple or a colonial fort? An anthropologist would analyze the politics of heritage. Non-monumental, prehistoric, and so-called “tribal” heritage often receives far less priority, funding, and public attention than the grand monuments of later, text-based, state-level societies. This reflects a bias in what we, as a nation, choose to value, remember, and preserve from our collective past.

The Exam Angle: How to Use This in Your Mains Answer

- Types of Questions Where It can be Used:

- “Discuss the salient features of the megalithic cultures of South India.”

- “What are the major challenges to the preservation of archaeological heritage in India?”

- GS-1 (Heritage): “The conflict between development and heritage conservation is a major issue in modern India. Discuss with examples.”

- Model Integration:

- On Megalithic Cultures (Paper 2): “The megalithic culture of South India is well represented by the dolmens of Kodaikanal in the Palani Hills. These burial structures provide crucial evidence of their mortuary practices, trade networks (indicated by carnelian beads), and sophisticated construction techniques, though this vital heritage is currently under severe threat from modern development.”

- On Heritage Management (Applied Anthro): “A major challenge in heritage management is the preservation of non-monumental archaeological sites. The case of the Kodaikanal dolmens, where over half have been destroyed for road construction and urban expansion in the last century, is a stark example of how priceless prehistoric heritage is being lost due to unchecked development and institutional neglect.”

- For GS-1 (Heritage): “The conflict between development and heritage is a critical national issue. In the Palani Hills of Tamil Nadu, for instance, 5,000-year-old megalithic dolmens are reportedly being dismantled for their stone to be used in modern construction, highlighting the urgent need for better implementation of conservation laws.”

Observer’s Take

The dolmens of Kodaikanal are more than just ancient graves; they are the first history books of the Tamil land, written in stone. For 5,000 years, they have stood as silent witnesses to the dawn of culture in the southern hills. The profound tragedy is that a single century of modernity has done more to erase them than fifty centuries of sun and rain. Their slow disappearance is a form of cultural amnesia we are inflicting upon ourselves. This case is a powerful reminder that heritage is not just about preserving grand palaces and forts; it is also about protecting the quiet, scattered stones that tell the very oldest stories of who we are.