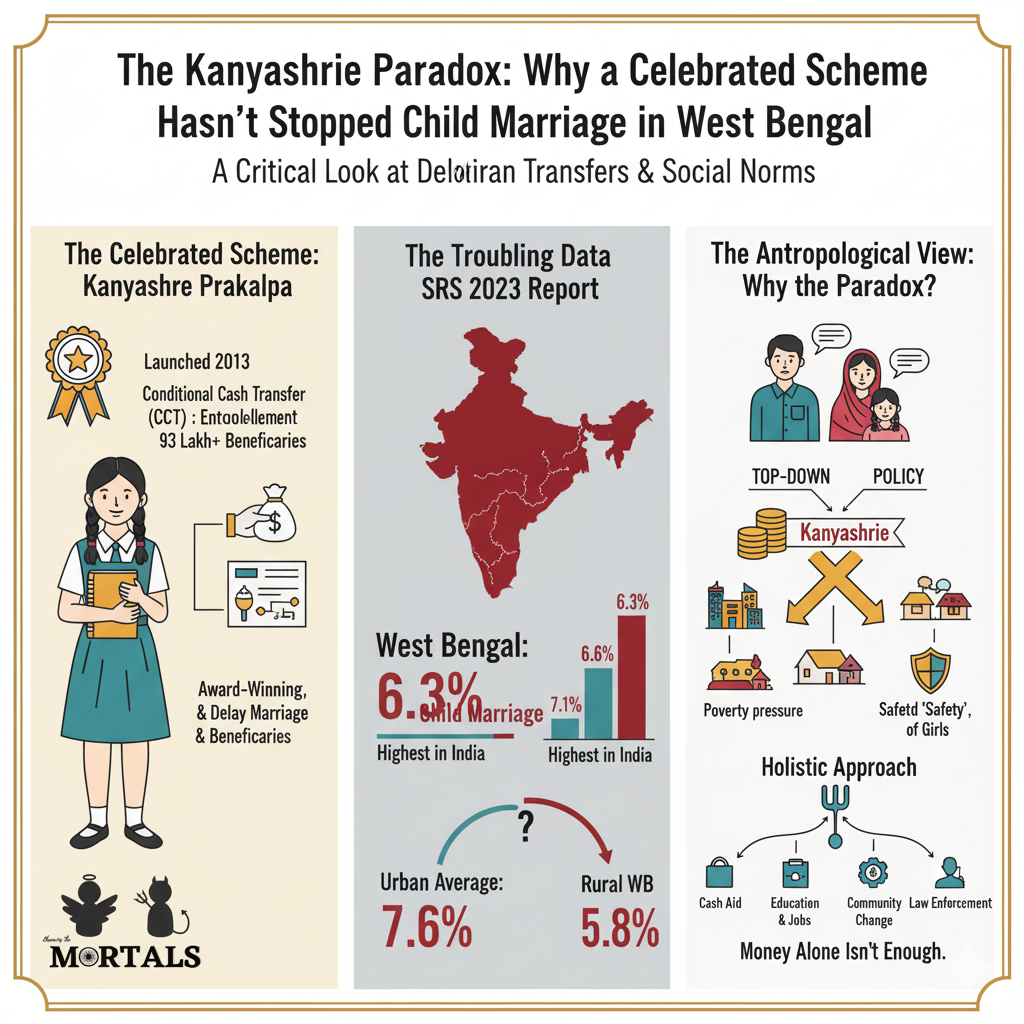

The Kanyashree Prakalpa is one of West Bengal’s most celebrated welfare schemes—a globally recognized, award-winning program designed to empower adolescent girls and eradicate the scourge of child marriage through financial incentives. It is, by all accounts, a policy success story. However, the latest official data from the Sample Registration System (SRS) report paints a starkly different and deeply troubling picture. West Bengal, the home of this celebrated scheme, now holds the unenviable distinction of having the highest rate of child marriage in India. This case study investigates the “Kanyashree Paradox,” asking a critical question: why is a massive, well-funded policy failing to solve a deep-rooted social problem?

The Information Box

Syllabus Connection:

- Paper 2: Chapter 2 (Demographic profile of India), Chapter 3 (Social Problems: Child Marriage), Chapter 9.1 (Problems of Women)

- Paper 1: Chapter 9 (Applied Anthropology: Policy Evaluation), Chapter 2.3 (Marriage), Chapter 8 (Social Change)

Key Concepts/Tags:

- Child Marriage, Kanyashree Prakalpa, Policy Paradox, Conditional Cash Transfer (CCT), Social Norms, West Bengal

The Setting: Who, What, Where?

The setting is the state of West Bengal. The data comes from the latest Sample Registration System (SRS) Statistical Report for 2023, released in September 2025. This official report is contrasted with the state’s flagship social welfare scheme, the Kanyashree Prakalpa, a conditional cash transfer (CCT) program launched in 2013. The core finding is that 6.3% of females in West Bengal are married before the legal age of 18, a rate that is nearly three times the national average of 2.1%.

The Core Argument: Why This Study Matters

This is a critical case study on the limitations of a specific type of top-down policy intervention.

- The “Kanyashree Paradox”: The central issue is the glaring contradiction between a massive, well-funded, and widely acclaimed government scheme and its apparent failure to achieve its primary objective. With over 93 lakh beneficiaries and a budget of hundreds of crores, the Kanyashree scheme’s reach is immense, yet the state’s child marriage rates remain stubbornly the highest in the country.

- The Limits of Economic Incentives: This case is a powerful, real-world critique of relying solely on economic incentives (like cash transfers) to solve a complex socio-cultural problem. The data suggests that while such schemes can provide partial relief, they are insufficient on their own to counter the deep-rooted structural pressures of poverty, the institution of dowry, and patriarchal social norms that compel families to marry off their daughters early.

- The Surprising Urban-Rural Dynamic: The data reveals a shocking paradox within the paradox. The SRS report indicates that the rate of child marriage in urban West Bengal (7.6%) is even higher than in its rural areas (5.8%). This directly challenges the simplistic assumption that modernization, education, and urban life automatically erode such traditional practices. It points towards the powerful persistence of entrenched cultural norms that transcend the rural-urban divide.

The Anthropologist’s Gaze: A Critical Perspective

- Top-Down Intervention vs. Bottom-Up Norms: An anthropologist would analyze this as a classic case of a top-down, state-led intervention failing to change a bottom-up, community-held social norm. The Kanyashree scheme is a transactional solution (the state offers money to keep a girl in school) to a problem that is deeply embedded in the cultural logic of kinship, family honor, and social security. The policy, by itself, does not change the underlying beliefs.

- The Emic View: The Logic of “Safety”: A deeper anthropological inquiry would focus on the emic (insider’s) perspective, particularly the parental perception of early marriage as a rational strategy to ensure the “safety” and “security” of their daughters. In a context of economic precarity and perceived social dangers, marrying a daughter off is often seen as a protective act that secures her future and safeguards the family’s honor. This powerful cultural logic is not easily overcome by a one-time grant of ₹25,000.

- The Need for a Holistic Approach: An applied anthropology perspective would argue that the solution cannot be a single scheme. It requires a multi-pronged, holistic approach that combines:

- Economic Incentives (like Kanyashree).

- Intensive, on-the-ground Social and Behavioral Change Communication (SBCC) to challenge patriarchal norms.

- Guaranteed access to quality higher education and safe, viable employment opportunities for women.

- Stricter and more consistent enforcement of the Prohibition of Child Marriage Act.

The Exam Angle: How to Use This in Your Mains Answer

- Types of Questions Where It can be Used:

- “Analyze the demographic trends related to marriage in India.”

- “Welfare schemes for women in India have had mixed success. Critically evaluate.”

- GS-1/2: “Child marriage remains a significant social problem in India despite legal prohibitions. Analyze the reasons and suggest measures.”

- Model Integration:

- On Child Marriage (Paper 2/GS-1): “Despite a national decline, child marriage remains a persistent problem with significant regional disparities, as highlighted by the latest SRS 2023 report. West Bengal, for example, records the highest rate at 6.3%, nearly three times the national average, indicating the failure of existing interventions in the state.”

- On Policy Evaluation (GS-2/Anthro): “The effectiveness of welfare schemes is often limited by deep-rooted social norms, a phenomenon known as the ‘policy paradox.’ The case of the Kanyashree scheme in West Bengal is a prime example, where the state’s celebrated cash transfer program has failed to significantly curb the nation’s highest child marriage rate, showing that economic incentives alone are insufficient.”

- To suggest solutions: “The stubborn persistence of child marriage in West Bengal, despite the Kanyashree scheme, underscores the need for a more holistic, anthropological approach. Any successful policy must combine financial incentives with intensive, on-the-ground community engagement to address the underlying social drivers, such as patriarchal norms and parental perceptions of girls’ safety and security.”

Observer’s Take

The data from West Bengal is a sobering but crucial reality check. It teaches us an important lesson in development and social policy: you cannot simply pay a deep-seated social problem to go away. The Kanyashree scheme is a well-intentioned and important part of the solution, but it is not a silver bullet. The stubborn persistence of child marriage is a powerful reminder that entrenched cultural norms are not easily swayed by financial transactions alone. Real, sustainable change requires not just supporting girls with cash, but transforming the very social, economic, and patriarchal environment that limits their choices and devalues their lives in the first place. It is a call for a deeper, more patient, and more holistic engagement with the communities we seek to help.