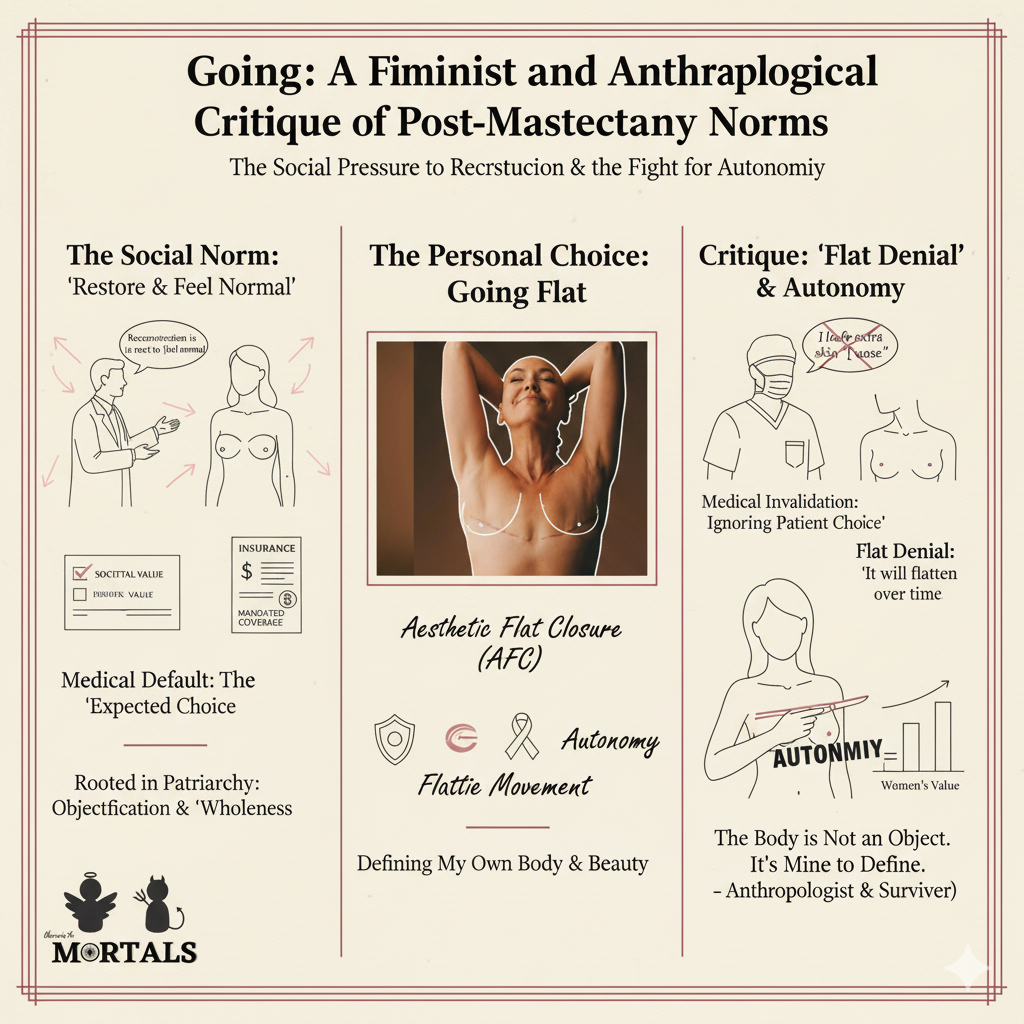

Breast reconstruction following a mastectomy is often presented as a routine, restorative, and near-obligatory step in the journey of breast cancer treatment—a way for a woman to “feel normal again.” But what if this “normal” is itself a powerful social and cultural pressure, rooted in patriarchal ideas about what a woman’s body should look like? In a stunningly personal and analytically sharp essay, anthropologist Arianna Huhn uses her own cancer diagnosis and decision to “go flat” to conduct an auto-ethnography of the medical system. This case study explores her journey and her powerful critique of the social pressures that shape one of the most personal decisions a woman can make.

The Information Box

Syllabus Connection:

- Paper 1: Chapter 9.6 (Medical Anthropology, Feminist Anthropology), Chapter 2.1 (Culture, Social Norms), Chapter 1.8 (Research Methods: Auto-ethnography)

Key Concepts/Tags:

- Medical Anthropology, Feminist Anthropology, Auto-ethnography, Aesthetic Flat Closure, Flattie Movement, Flat Denial, Patriarchy

The Setting: Who, What, Where?

The setting is the modern U.S. medical system, and the case study is an auto-ethnography—an analysis based on the personal experiences of the author, cultural anthropologist Arianna Huhn, following her breast cancer diagnosis and double mastectomy. The context is a medical culture where the Women’s Health and Cancer Rights Act (WHCRA) mandates insurance coverage for breast reconstruction, effectively making it the default and expected pathway for patients. This has given rise to a grassroots counter-movement known as the “flattie movement,” which advocates for Aesthetic Flat Closure (AFC) as a positive and valid choice.

The Core Argument: Why This Study Matters

This is a critical anthropological examination of how cultural norms are embedded within medical practice.

- Reconstruction as a Social Norm, Not a Neutral Choice: Her central argument is that breast reconstruction is not offered as one of several equal options, but is presented as the default, normative, and expected “next step.” This social pressure is evidenced by the surgeon’s initial assumption and surprise, the insurance navigator’s talk of helping the patient “feel normal,” and friends’ confused reactions. The choice to “go flat” is framed as a strange deviation from the norm.

- A Feminist Critique of Medical Practice: Huhn argues that this powerful default towards reconstruction is rooted in patriarchy. It reflects what she calls an “asymmetrical binary whereby a woman’s value depends in large part on her objectification.” The intense pressure to reconstruct, she contends, is fundamentally a pressure to restore a culturally specific “normal” female silhouette, which is deeply equated with femininity, sexual desirability, and social wholeness.

- “Flat Denial” as a Form of Medical Invalidation: It introduces the powerful grassroots concept of “flat denial.” This is what happens when a patient explicitly requests a flat closure, but the surgeon ignores her wishes, either by leaving extra skin “just in case” she changes her mind, or by performing an incompetent closure. The author’s own painful experience of being left with a botched chest contour and being told “it will flatten over time” is a stark example. This reveals how a woman’s aesthetic autonomy is dismissed when it deviates from the norm, implying she is not “entitled to an aesthetic preference” if she rejects implants.

The Anthropologist’s Gaze: A Critical Perspective

The entire essay is an application of the anthropological gaze, but it highlights several key methods and insights.

- Auto-Ethnography as a Powerful Method: This case study is a classic example of auto-ethnography, a research method where the anthropologist uses their own lived experience as primary data to analyze broader cultural patterns. Huhn uses her personal, vulnerable journey through the medical system to interrogate its taken-for-granted societal norms and patriarchal assumptions.

- The Cultural Construction of the “Normal” Body: The case study is a brilliant medical anthropology analysis of how the “normal” or “whole” body is a cultural construct, not a biological given. It shows how the medical system, backed by law and immense social pressure, works to produce and restore a very specific version of the female body, implicitly defining a woman without breast mounds as abnormal, incomplete, or in need of “fixing.”

- Language as a Diagnostic Tool: An anthropologist would focus on the power of language in her essay. The surgeon’s confusion between “flat” and “flap,” the nurse’s concern for what her “husband will think,” and the community’s own empowering terms like “flattie,” “Unicorns,” and “Amazons” are not just words. They are rich data that reveal the powerful, and often conflicting, cultural assumptions at play.

The Exam Angle: How to Use This in Your Mains Answer

- Types of Questions Where It can be Used:

- “Critically analyze the contribution of feminist anthropology to the discipline.”

- “How does medical anthropology help in understanding the cultural dimensions of health, illness, and the body?”

- “Discuss the significance of auto-ethnography as a research method in anthropology.”

- Model Integration:

- On Medical Anthropology: “Medical anthropology critically examines how cultural norms shape medical practice. For example, Arianna Huhn’s auto-ethnographic account of her mastectomy reveals how the medical system’s default preference for breast reconstruction is not a purely objective medical choice, but is deeply rooted in societal norms about female body image and ‘normalcy’.”

- On Feminist Anthropology: “Feminist anthropology critiques how patriarchal values are embedded in institutions. The social and medical pressure on women to undergo breast reconstruction, and the phenomenon of ‘flat denial’ where a patient’s wish to ‘go flat’ is ignored, can be analyzed as a medical practice rooted in the cultural objectification of the female body.”

- On Research Methods: “While traditional ethnography often focuses on the ‘other,’ auto-ethnography uses the researcher’s own experience as powerful data. Arianna Huhn’s analysis of her own cancer journey is a prime example, using her personal experience to offer a critical perspective on the culture of the U.S. medical system and its patriarchal underpinnings.”

Observer’s Take

Arianna Huhn’s essay is a profound and courageous piece of anthropology. It takes one of the most personal, vulnerable, and frightening experiences a person can face and masterfully turns it into a sharp, analytical lens. She reminds us that the hospital room and the surgeon’s office are not culture-free zones; they are, in fact, saturated with our society’s deepest and often unexamined assumptions about gender, beauty, and what it means to be a “normal” woman. Her story is a powerful testament to a woman’s right to define her own body and her own recovery, and a call for all of us to see and value women as whole beings, not as objects to be reconstructed according to a prescribed ideal.

Source

- Title: When Women Say “Ta-Ta” to Ta-Tas

- Author: Arianna Huhn

- Publication: SAPIENS.org

- Link: https://www.sapiens.org/culture/women-breast-cancer-reconstructive-surgery-going-flat/