The Tibetan plateau is one of the world’s most extreme environments, a land of thin air and biting cold. For millennia, indigenous Tibetans have thrived there, while newcomers struggle to adapt. Anthropologists have long studied their unique adaptations to low oxygen, but what about the cold? A fascinating new study published in the Journal of Physiological Anthropology uses a simple but brutal “ice water test” to find a clear, measurable difference between the bodies of indigenous Tibetans and long-term Han Chinese migrants. The results reveal a deep story of evolutionary adaptation written in their very blood vessels.

The Information Box

Syllabus Connection:

- Paper 1: Chapter 11.1 (Human Ecology: Adaptation to extreme environments – high altitude, cold), Chapter 9.2 (Race and racism: biological basis of racial variation), Chapter 1.3 (Scope of Physical Anthropology)

Key Concepts/Tags:

- Physiological Anthropology, Human Adaptation, High-Altitude Adaptation, Cold Adaptation, Cold-Induced Vasodilation (CIVD), Tibetans, Han Chinese

The Setting: Who, What, Where?

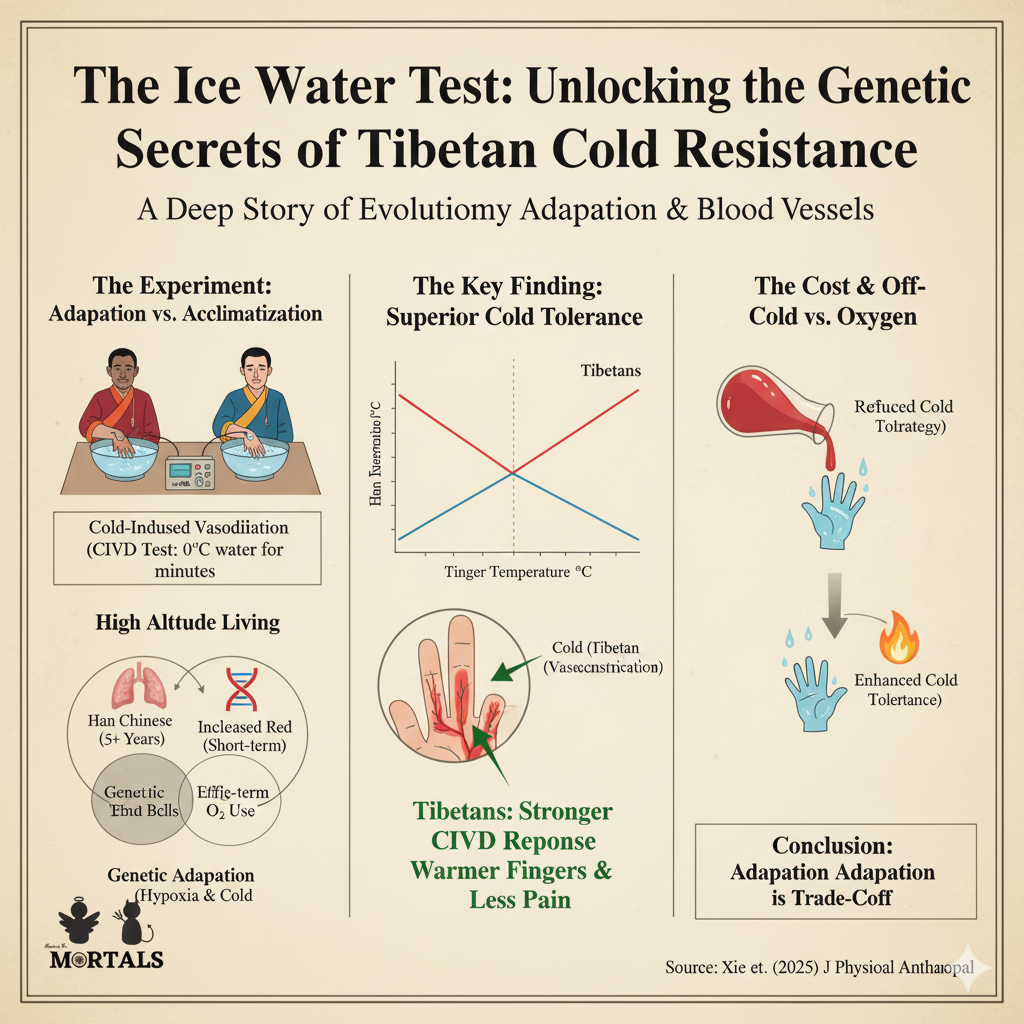

The research was conducted by a team of scientists in the high-altitude city of Shigatse (4,200m) in Tibet. The study involved two groups of men who had both lived at high altitude for over five years: a group of indigenous Tibetans and a group of migrant Han Chinese. The core of the experiment was the Cold-Induced Vasodilation (CIVD) test. This involves immersing a participant’s finger in 0°C water for 30 minutes and precisely measuring how the skin temperature responds. A strong CIVD response—where blood vessels paradoxically dilate to re-warm the finger—is a key indicator of superior cold tolerance.

The Core Argument: Why This Study Matters

This study provides a clear physiological marker that distinguishes a classic case of long-term human adaptation from short-term adjustment.

- Tibetans Have Superior Cold Tolerance: The key finding was that Tibetans demonstrated a measurably superior response to the cold. During the ice water immersion, their fingers stayed significantly warmer, and their CIVD response was stronger than that of their Han counterparts. Furthermore, they also perceptually experienced the test differently, reporting less pain and more comfort. This is direct physiological and subjective evidence of a better-adapted thermoregulatory system.

- Adaptation vs. Acclimatization Made Visible: The study perfectly illustrates this core anthropological concept. The Han participants, having lived at high altitude for over five years, had acclimatized (made individual, short-term physiological adjustments). However, they could not match the performance of the Tibetans, whose superior cold tolerance is the result of thousands of years of evolutionary adaptation—a change written in their genetic heritage.

- The Hidden “Cost” of Han Adaptation: The study hints at the underlying mechanism. A common way the bodies of non-adapted people acclimatize to low oxygen is by producing more red blood cells (a condition called erythrocytosis). The study found that, in general, higher red blood cell counts were correlated with worse cold tolerance, likely because thicker, more viscous blood struggles to circulate in the tiny capillaries of the fingertips. This suggests the common Han strategy for dealing with low oxygen comes at the cost of their resistance to cold—a trade-off that Tibetans, with their unique genetic adaptations for more efficient oxygen use, do not have to make.

The Anthropologist’s Gaze: A Critical Perspective

- The Bio-Cultural Approach: A broader anthropological perspective would seek to integrate this physiological data with cultural practices. How do traditional Tibetan cultural adaptations—such as a diet rich in barley and yak butter, unique clothing, or specific activity patterns—interact with their genetic predispositions to produce their overall mastery of the cold? This study is purely biological, but a full anthropological account would be bio-cultural.

- Human Plasticity on Display: This study is a fantastic example of human plasticity. It shows how two different human populations, when faced with the same environmental stress (cold and hypoxia), exhibit different adaptive pathways. One pathway is based on long-term genetic selection for efficiency (Tibetans), and the other is based on more immediate, but less efficient, physiological compensation (Han).

- Beyond “Race”: It is crucial to understand that this is a modern, scientific way of studying human biological variation, not a justification for old-fashioned racial typologies. The study is not about proving one “race” is superior. It is about understanding how specific, historically isolated populations develop unique and remarkable genetic adaptations to the extreme local environments in which their ancestors lived for millennia.

The Exam Angle: How to Use This in Your Mains Answer

- Types of Questions Where It can be Used:

- “Discuss the various ways in which human beings adapt to extreme cold and high-altitude environments.”

- “Distinguish between acclimatization and adaptation with suitable anthropological examples.”

- “What is the scope and methodology of Physiological Anthropology?”

- Model Integration:

- On High-Altitude Adaptation: “Human adaptation to high altitude involves not just coping with hypoxia but also extreme cold. A recent study on Cold-Induced Vasodilation (CIVD) provided physiological evidence that indigenous Tibetans have a superior vascular response to cold immersion compared to long-term Han residents, demonstrating a deep, evolutionary adaptation.”

- On Adaptation vs. Acclimatization: “The difference between long-term genetic adaptation and short-term acclimatization is clearly visible in high-altitude populations. For instance, while Han migrants in Tibet acclimatize by increasing their red blood cell count, this can impair cold tolerance. Tibetans, in contrast, have unique genetic adaptations that allow for both efficient oxygen use and a superior cold response, as shown in recent CIVD studies.”

- On Methods in Physical Anthro: “Modern physical anthropology uses experimental methods to study human biological variation. For example, the use of the CIVD test to compare the finger temperature responses of Tibetans and Han Chinese provides quantitative, physiological data on their differential adaptation to cold.”

Observer’s Take

This study is a fascinating deep dive into the physiological poetry of human evolution. It shows how, over thousands of years, the extreme environment of the Tibetan plateau has sculpted a unique biological masterpiece in its people. The ability of a Tibetan’s blood vessels to dance with the cold—opening up to perfuse and protect the flesh from frostbite—is a story written not in ancient texts, but in their genes. It is a powerful, scientific testament to the profound difference between simply getting used to a place and truly, biologically, belonging to it. This research is a crucial reminder that our bodies are living records of our ancestors’ long journeys and their remarkable, and varied, capacity to adapt and thrive.

Source

- Title: Characteristics of cold-induced vasodilation among Tibetans and Han Chinese at high altitudes

- Authors: Hong-Chen Xie, et al.

- Publication: Journal of Physiological Anthropology (2025)

- Link: https://jphysiolanthropol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40101-025-00404-8