For over a century, the textbook image of a hunter-gatherer society has been a simple one: a small, isolated band of 25-50 people, bound by kinship, perpetually moving in a desperate, nomadic search for their next meal. This picture has long defined our understanding of the “primitive” past. But what if this picture is completely wrong? A new wave of anthropological research, beautifully articulated in an essay by Cecilia Padilla-Iglesias on her fieldwork with the Mbendjele BaYaka people of Congo, argues just that. This research suggests that hunter-gatherers are not small and isolated; they are part of vast, city-sized social networks. And their constant movement is not a sign of desperation, but a deliberate and brilliant strategy to maintain those large, complex societies.

The Information Box

Syllabus Connection:

- Paper 1: Chapter 1.8 (Prehistoric Archaeology: Hunting & Gathering Bands), Chapter 2.5 (Social Organization), Chapter 3 (Economic Anthropology), Chapter 6 (Anthropological Theories: Critique of Unilineal Evolution)

Key Concepts/Tags:

- Hunter-Gatherer, Mobility, Social Networks, Man the Hunter, Mbendjele BaYaka, Cumulative Culture, Sedentism

The Setting: Who, What, Where?

The contemporary setting is the work of researchers like Cecilia Padilla-Iglesias with the Mbendjele BaYaka, a mobile hunter-gatherer group in the Congolese rainforest. This new research, however, is framed as a direct critique and revision of the influential but outdated narrative of social evolution that emerged from the landmark 1966 “Man the Hunter” symposium. While that symposium was revolutionary for its time (introducing ideas like the “original affluent society”), it still promoted the idea that hunter-gatherers lived in small, simple bands and that settling down (sedentism) was a form of inevitable progress.

The Core Argument: Why This Study Matters

This new perspective is a major revision of how we understand not just hunter-gatherers, but the very nature of human social complexity.

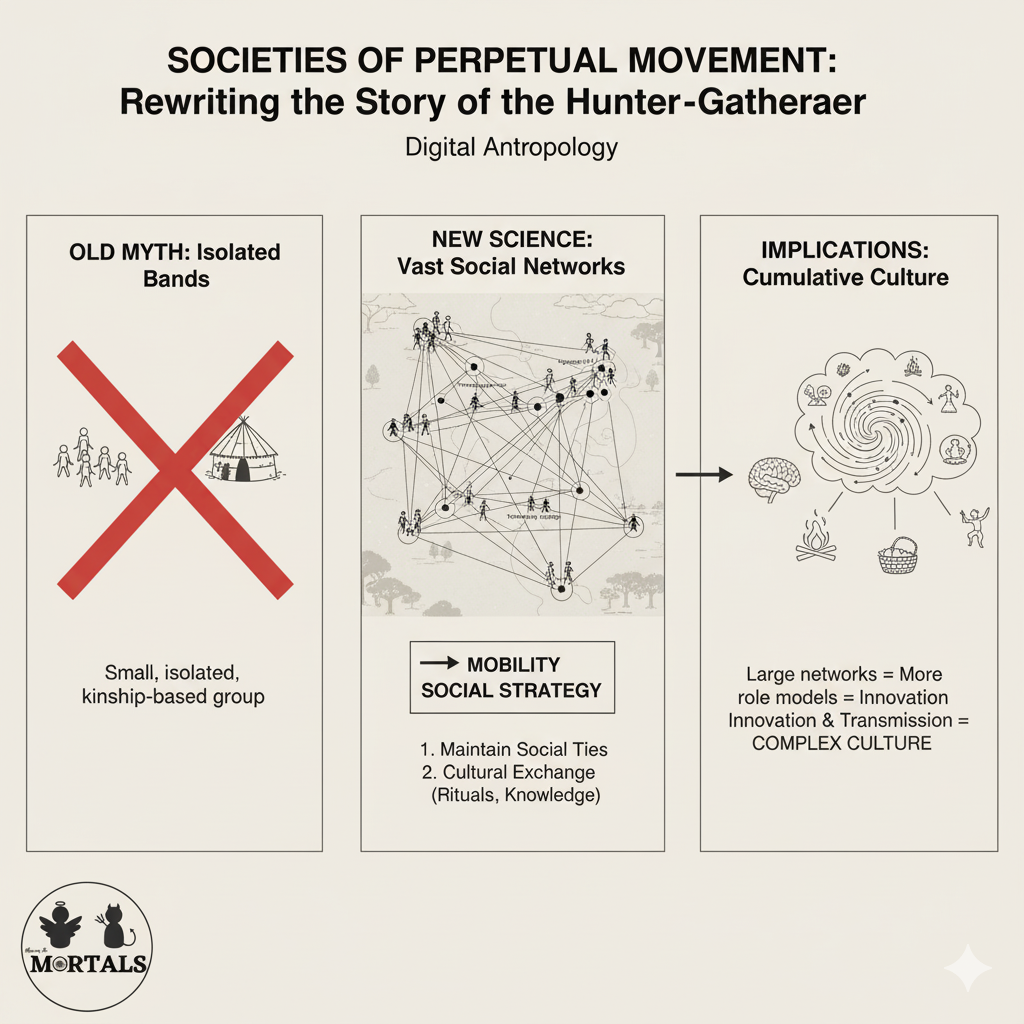

- Debunking the “Small, Isolated Band” Myth: The central argument is that the classic image of the tiny, isolated band is a methodological illusion. Early anthropologists were only seeing one temporary camp, like a single house in a vast city, and mistaking it for the entire society. The new research argues that these small camps are merely temporary nodes in a vast, geographically dispersed social network that can span hundreds of kilometers and connect hundreds, if not thousands, of individuals.

- Mobility as a Social Strategy (Not Just for Food): The essay powerfully refutes the idea that hunter-gatherers move only because local food resources are depleted. Mobility is a deliberate and essential social strategy with several key functions:

- To Maintain Social Ties: To visit distant kin, find spouses from outside the immediate local group (which is crucial for genetic diversity), and maintain friendships and alliances.

- To Facilitate Cultural Exchange: To travel to participate in large-scale ceremonies (like the eboka), to trade rituals and knowledge, and to learn new skills (e.g., new uses for medicinal plants).

- Mobility as the Engine of Human Culture: This is a crucial theoretical insight. The large social networks maintained through mobility provide individuals with access to a huge pool of “role models” (one study estimated ~300 for a Hadza adult, compared to ~20 for a chimpanzee). This large, interconnected network is what allows for the innovation, transmission, and accumulation of complex, cumulative culture—one of the defining traits of our species. Small, isolated groups struggle to retain complex skills; large, interconnected ones excel at it.

The Anthropologist’s Gaze: A Critical Perspective

The entire essay is a critical gaze at older models, but it highlights several key analytical points.

- A Critique of the “Sedentary Bias”: The essay is a powerful critique of the “sedentary bias” that has long dominated anthropology and popular thought. Because we live in a settled world, we tend to view mobility as a primitive, inefficient, or problematic way of life, and see sedentism as the universal and unquestioned goal of progress. This new research shows this is a deeply ingrained ethnocentric assumption.

- Re-evaluating the Agricultural “Revolution”: The argument powerfully challenges the idea of agriculture as a definitive, one-way street to a better life. It provides strong evidence to support this critique:

- Examples of Reversal: Groups like the Numic-speakers of North America actually abandoned agriculture to return to a more adaptive foraging lifestyle.

- The Costs of Settling: Studies of groups like the Agta of the Philippines show that when they adopt farming and become sedentary, their workload increases dramatically (especially for women) and their rates of disease and mortality go up.

- A New Model for Social Complexity: The traditional model of social evolution equates complexity with population density, permanent structures, and hierarchy (villages, cities, states). This new research proposes an alternative model: complexity through a distributed network. A hunter-gatherer society can be vast and complex, but its form is a “mobile constellation” of interconnected nodes, rather than a single, fixed center.

The Exam Angle: How to Use This in Your Mains Answer

- Types of Questions Where It can be Used:

- “The classic anthropological model of the ‘band’ as a small, isolated group is an oversimplification. Critically evaluate.”

- “Analyze the role of mobility in the social and cultural life of hunter-gatherer societies.”

- “The adoption of agriculture was not an inevitable path to progress. Discuss with examples.”

- Model Integration:

- On Hunter-Gatherer Society: “The classic view of hunter-gatherers as living in small, isolated bands is being overturned by modern research. Anthropologists like Cecilia Padilla-Iglesias argue that these small camps are actually nodes in vast, complex social networks maintained through deliberate mobility. Mobility is thus a strategy to create a large society, not a symptom of a simple one.”

- On Cumulative Culture: “The emergence of complex, cumulative culture in humans is directly linked to the size of our social networks. New research on mobile hunter-gatherers suggests their ‘perpetual movement’ was a key strategy for maintaining large, inter-connected populations, which provided access to hundreds of ‘role models’ and facilitated the rapid transmission and innovation of cultural traits.”

- To critique the Agricultural Revolution: “The transition to agriculture was not an inevitable ‘progression.’ Evidence from groups like the Agta of the Philippines shows that sedentarism can lead to higher disease rates and a significantly increased workload, especially for women, supporting the argument that a mobile foraging lifestyle was in many ways a highly efficient and desirable adaptation.”

Observer’s Take

This new wave of research on hunter-gatherer mobility is a profound and humbling corrective to one of our most cherished stories of human “progress.” It reveals that for millennia, we have likely misunderstood the very nature of these societies. We saw their small, temporary camps and assumed their social worlds were equally small. We were wrong. Their worlds were vast, connected by an intricate web of movement, kinship, ritual, and exchange that spanned entire landscapes. This is more than just an academic revision; it’s a powerful lesson. It reminds us that there is more than one way to build a large and complex human society, and that progress is not always a straight line leading to a settled destination. Sometimes, the most resilient, adaptive, and culturally rich path is one of perpetual movement.

Source

- Title: Societies of perpetual movement

- Author: Cecilia Padilla-Iglesias

- Publication: Aeon

- Link: https://aeon.co/essays/the-hunter-gatherers-of-the-21st-century-who-live-on-the-move