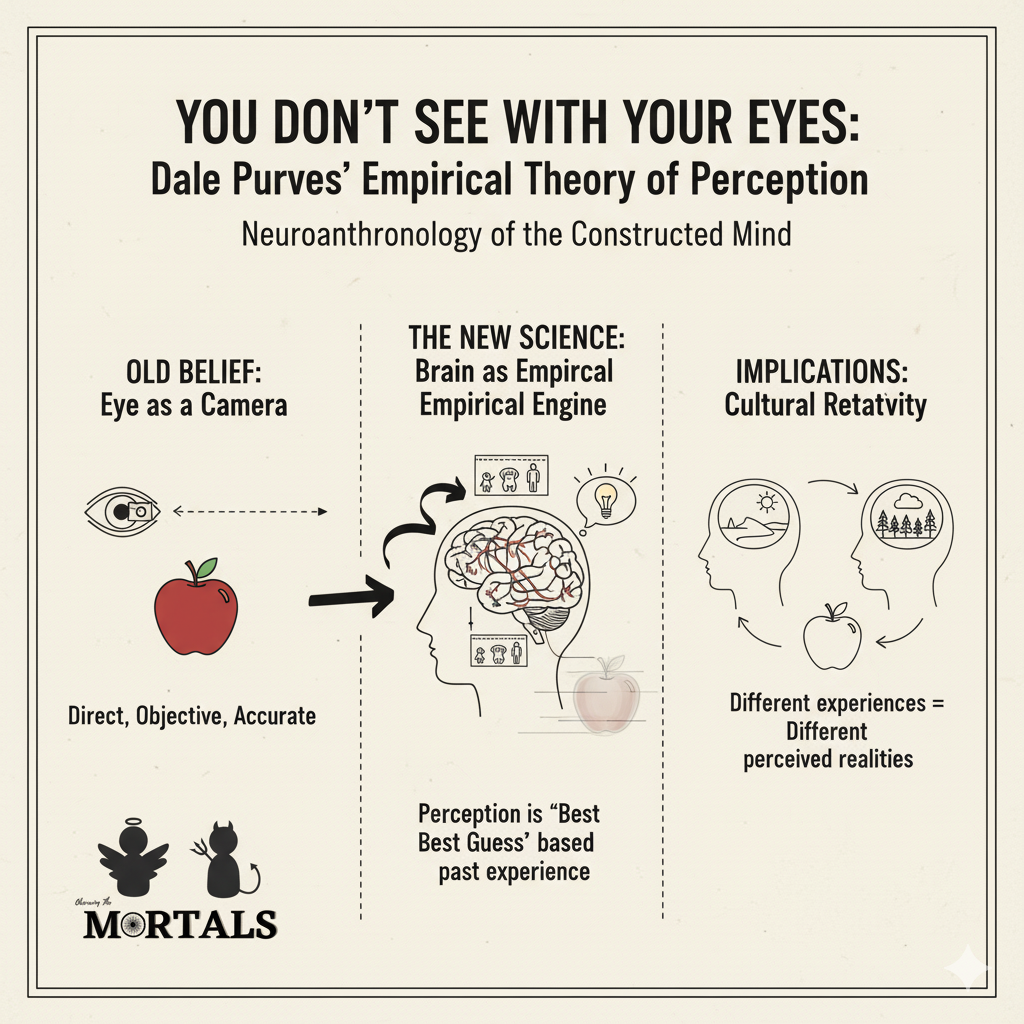

We live with an intuitive and powerful conviction: that our eyes act like cameras, delivering a direct, accurate, and objective picture of the world to our brains. But what if this is a profound illusion? What if your brain, locked in the dark, silent vault of your skull, has no direct access to reality at all? This is the radical and compelling argument at the heart of the life’s work of the great neuroscientist Dale Purves. He argues that everything you see, hear, and feel is not a reflection of the world, but a construction by your brain—a “best guess” about reality based entirely on your past experiences.

The Information Box

Syllabus Connection:

- Paper 1: Chapter 1.7 (The Biological Basis of Life/Behavior), Chapter 1.2 (Relationship with Psychology & Neuroscience), Chapter 12 (New Perspectives: Neuroanthropology, Cognitive Anthropology)

Key Concepts/Tags:

- Dale Purves, Neuroanthropology, Perception, Empirical Theory of Mind, Trophic Theory, Inverse Optics Problem

The Setting: Who, What, Where?

This is a case study of a major scientific theory developed by Dale Purves, an influential American neuroscientist. His work is not a single ethnography but a career-spanning intellectual journey that moves from developmental neurobiology to the philosophy of perception. His ideas, synthesized in works like Body and Brain (1988) and his later research on visual illusions, build on the foundations laid by thinkers like philosopher George Berkeley and scientist Hermann von Helmholtz. Purves’s laboratory is the human visual system itself, and his data comes from a vast range of experiments on how we perceive basics like color, brightness, and geometry.

The Core Argument: Why This Study Matters

Purves’s work provides a fundamental challenge to the way we think about the brain and its relationship to reality.

- The Brain as an Empirical Engine, Not a Computer: The central argument is that the brain does not function like a computer that passively processes objective features of the world (“red + round + sweet = apple”). Instead, it operates on a wholly empirical basis. It builds a statistical model of reality based on the accumulated experiences of both our species’ evolutionary history and our own individual lives.

- Perception as a “Best Guess,” Not a Photograph: Our sensory input is fundamentally ambiguous. For example, our 2D retina receives the same signal from a small object nearby as it does from a large object far away (the “inverse optics problem”). Because of this ambiguity, Purves argues that perception can never be a direct readout of the world. Instead, it is an unconscious inference or a “best guess” about the source of the sensory signal, based entirely on what has been a successful and useful way of interpreting similar signals in the past. Your brain shows you a version of reality that has proven useful for survival, not the one that is physically “true.”

- The Brain and Body as an Inseparable Network: Purves’s early, groundbreaking work on Trophic Theory provides the biological foundation for this idea. He showed that the brain’s very wiring is not pre-programmed but is dynamically shaped by the body it is connected to and the environment it interacts with. In essence, our physical experiences literally build the brain that will then interpret all our future experiences.

The Anthropologist’s Gaze: A Critical Perspective

- A Neurological Basis for Cultural Relativity: Purves’s theory, while coming from neuroscience, provides a powerful biological basis for the core anthropological concept of cultural relativity. If our perception of the world is built from our unique experiences, then it follows that people who grow up in vastly different cultural and physical environments will, in a very real and biological sense, perceive the world differently. Their brains have been empirically trained on a different dataset of experiences. This gives a neurological grounding to ideas like the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis.

- Neuroanthropology in Action: This is a perfect case study for the emerging field of neuroanthropology. It uses hard-won insights from neuroscience to answer fundamental anthropological questions: How do we construct our worldview? What is the relationship between our biology and our culture? It shows how the brain is not just a static biological object but a dynamic, cultural, and historical one, literally shaped by a lifetime of interaction with the world.

- A Critique of “Feature Detection”: Purves’s empirical theory is a direct challenge to the more mainstream “feature detection” model in neuroscience, which suggests the brain builds a picture of the world by assembling simple features like lines, edges, and colors. Purves’s model is more holistic, arguing that we perceive based on the statistical history of entire scenes and our past interactions with them, not just by adding up the parts.

The Exam Angle: How to Use This in Your Mains Answer

- Types of Questions Where It can be Used:

- “Discuss the biological basis of human behavior and cognition.”

- “Analyze the relationship between anthropology and other disciplines like psychology and neuroscience.”

- Essay: On topics of reality, perception, knowledge, or the nature of consciousness.

- Model Integration:

- On Neuroanthropology (Paper 1, Ch 12): “Neuroanthropology explores how our brains construct our perceived reality. The work of neuroscientist Dale Purves, for instance, provides an ’empirical theory’ of perception, arguing that we see the world not as it is, but in a way that reflects our past individual and evolutionary experiences, giving a biological basis to cultural differences in perception.”

- On the Biological Basis of Behavior: “The biological basis of perception is not a simple camera-like recording of the world. As Dale Purves’s research shows, the brain actively constructs what we see based on learned associations. This is powerfully demonstrated by the case of newly sighted cataract patients, who cannot make sense of the visual world without first building a library of experience.”

- For an Essay on Reality: “Our intuitive belief that we perceive an objective reality is a neurological illusion. As thinkers like Dale Purves have argued, our brain is locked in a skull and only receives ambiguous sensory data. Our ‘reality’ is therefore a construction, a ‘best guess’ based on what has proven useful for survival, a finding with profound implications for understanding cultural differences in worldview.”

Observer’s Take

Dale Purves’s life’s work is a journey to the heart of one of philosophy’s oldest questions: how can we truly know the world? His answer is both humbling and profound: we can’t, at least not directly. Our brain, locked in darkness and silence, doesn’t show us the world as it is; it shows us a world that is useful for us. Perception, in this view, is not an act of passive discovery, but an active act of creation, moment by moment. It’s a powerful reminder that the reality each of us experiences is not a universal truth, but a personal, biological, and cultural masterpiece, painted with the unique brushstrokes of our own history.

Source

- Title: Brain man

- Author: Asif Ghazanfar

- Publication: Aeon

- Link: https://aeon.co/essays/dale-purves-the-neuroscientist-who-makes-sense-of-the-brain