We live in a world governed by “market forces.” We are told that the self-regulating market is the most natural and efficient way to organize society. But what if this entire idea is a modern myth? In his 1944 masterpiece, The Great Transformation, the economic historian and anthropologist Karl Polanyi offered a devastating counter-narrative. He argued that for all of human history before the Industrial Revolution, the economy was never a separate sphere; it was “embedded” in social life. This case study explores his profound argument that the creation of the free market was a violent act of “dis-embedding” that required society to turn its most sacred elements—human life and nature itself—into sellable objects.

The Information Box

Syllabus Connection:

- Paper 1: Chapter 3 (Economic Anthropology: Substantivism vs. Formalism, Exchange), Chapter 6 (Anthropological Theories), Chapter 10 (Development Anthropology)

Key Concepts/Tags:

- Karl Polanyi, The Great Transformation, Embeddedness, Fictitious Commodities, Substantivism, Double Movement, Economic Anthropology

The Setting: Who, What, Where?

This is a foundational work of economic history and anthropology by Karl Polanyi (1886-1964). His ideas are laid out in his book, The Great Transformation, written during the chaos of World War II. Polanyi was not a traditional village ethnographer; he was a grand theorist analyzing a massive historical shift. His primary case study was the Industrial Revolution in 19th-century England, which he used as the archetype for understanding the birth of the modern market economy and the subsequent global catastrophes (like the Great Depression and the rise of Fascism) that he saw as its inevitable result.

The Core Argument: Why This Study Matters

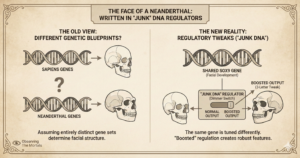

Polanyi’s work provided the intellectual foundation for the Substantivist school of economic anthropology. He argued that the modern market economy is a unique and dangerous anomaly in human history.

- The “Embedded” Economy (The “Before”): Polanyi’s first great insight was that in almost all pre-modern and non-Western societies, the economy is “embedded” within social and political relationships. It is not a separate, autonomous sphere. Exchange is driven by social principles like:

- Reciprocity (like the Kula Ring or gift-giving)

- Redistribution (a central authority, like a chief, collecting and re-allocating goods) The goal is social solidarity and prestige, not individual profit.

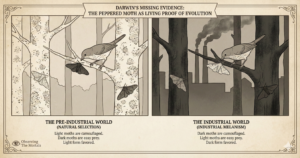

- The “Great Transformation” (The Violent “After”): The Industrial Revolution, he argued, was a violent rupture that “dis-embedded” the economy from society for the first time. This created the new, radical idea of a “self-regulating market” that was seen as an independent force of nature, like gravity, to which society must obey, not the other way around.

- The “Fictitious Commodities”: This is his most powerful and famous concept. To create this new system, society had to do something profoundly unnatural: it had to take three things that are not produced for sale and pretend they were mere commodities to be bought and sold at a market price.

- Labor (which is just another name for a human life)

- Land (which is just another name for the natural world)

- Money (which is a social symbol of value, not a product) Treating human life and the natural world as “fictitious commodities” subject to the “Satanic Mill” of the market, he argued, would inevitably destroy the fabric of society and the environment.

- The “Double Movement”: Because this system is so unnatural and destructive, Polanyi argued that it automatically triggers a “double movement.” The more the market tries to expand, the more society, in a desperate act of self-protection, fights back. Society demands the creation of social safety nets, labor laws, environmental regulations, and central banks to protect itself from the market’s ravages. For Polanyi, the social crises of the 20th century were the logical end-point of a society defending itself from a system that was trying to kill it.

The Anthropologist’s Gaze: A Critical Perspective

- Founder of the Substantivist School: Polanyi’s work is the basis of the Substantivist school of economic anthropology. This school argues that “economics” means different things in different cultures (the substantive definition) and that it is an ethnocentric error to apply our modern, profit-based economic models (the formalist definition) to all human societies.

- Is the “Before” Too Romanticized?: Critics have questioned whether Polanyi’s vision of the “embedded” pre-capitalist world was too romanticized. Was the market really so absent? Historians have pointed to significant evidence of price-making markets and profit motives in many ancient and non-Western societies, suggesting the “dis-embedding” was not as absolute as he claimed.

- Enduring Contemporary Relevance: This is Polanyi’s greatest strength. His critique is arguably more relevant today than when he wrote it. Modern debates over neoliberal globalization, climate change (the cost of treating nature as a commodity), the gig economy (the precarity of “labor” as a commodity), and financial crises (the instability of “money” as a commodity) are all perfect, real-world examples of Polanyi’s “fictitious commodities” and the “double movement.”

The Exam Angle: How to Use This in Your Mains Answer

- Types of Questions Where It can be Used:

- “Critically evaluate the Formalist-Substantivist debate in economic anthropology.”

- “What is an ’embedded’ economy? Discuss with ethnographic examples.”

- “Analyze the anthropological critiques of the modern market system.”

- Model Integration:

- On the Substantivist Debate: “The Substantivist school, founded on the work of Karl Polanyi, argues that the economy in most societies is ’embedded’ in social relations. Polanyi used this concept to argue that the modern, self-regulating market is a historical anomaly, not a universal human default.”

- To define “Embeddedness”: “An ’embedded’ economy, a concept from Karl Polanyi, is one where exchange is governed by social principles like reciprocity and redistribution rather than pure profit. His work ‘The Great Transformation’ analyzed the historical ‘dis-embedding’ of the economy from society during the Industrial Revolution.”

- For a critical view of globalization: “Karl Polanyi’s concept of ‘fictitious commodities’—land, labor, and money—provides a powerful anthropological critique of neoliberal globalization. He argued that treating human life and nature as mere market commodities is socially and ecologically unsustainable and will provoke a ‘double movement’ of societal self-protection.”

Observer’s Take

Karl Polanyi’s work is an intellectual earthquake. It tears down the wall that separates “the economy” from “society” and reveals it as a modern, artificial, and dangerous construction. The Great Transformation is a powerful moral argument that the most important things in life—our communities, our natural world, and our human dignity—must never be subjected to the cold, impersonal logic of the free market. His central message is a timeless and urgent one: the economy was made to serve society, not the other way around. Since we are the ones who built this “Satanic Mill,” we also have the power—and the profound responsibility—to tame it.