When Charles Darwin proposed his theory of natural selection, he was forced to argue based on the deep past—fossils, finch beaks, and the slow march of geological time. His one regret was that he couldn’t see evolution in action within a single human lifetime. Decades later, a different kind of British biologist, H. B. D. Kettlewell, would provide that very proof, not in a remote, exotic land, but in the soot-blackened forests of industrial England. His subject? The humble peppered moth. This case study explores Kettlewell’s “most beautiful experiment in evolutionary biology,” a series of brilliant field tests that, for the first time, allowed humanity to watch natural selection in real time.

The Information Box

Syllabus Connection:

- Paper 1: Chapter 1.4 (Principles of Evolution: Natural Selection, Industrial Melanism), Chapter 10 (Ecological Anthropology)

- Paper 2: Chapter 1 (Foundations of Indian Anthropology – context for Darwinian thought)

- GS-3: Environment & Ecology

Key Concepts/Tags:

- Natural Selection, Industrial Melanism, Peppered Moth (Biston betularia), H.B.D. Kettlewell, Natural Experiment, Cryptic Coloration

The Setting: Who, What, Where?

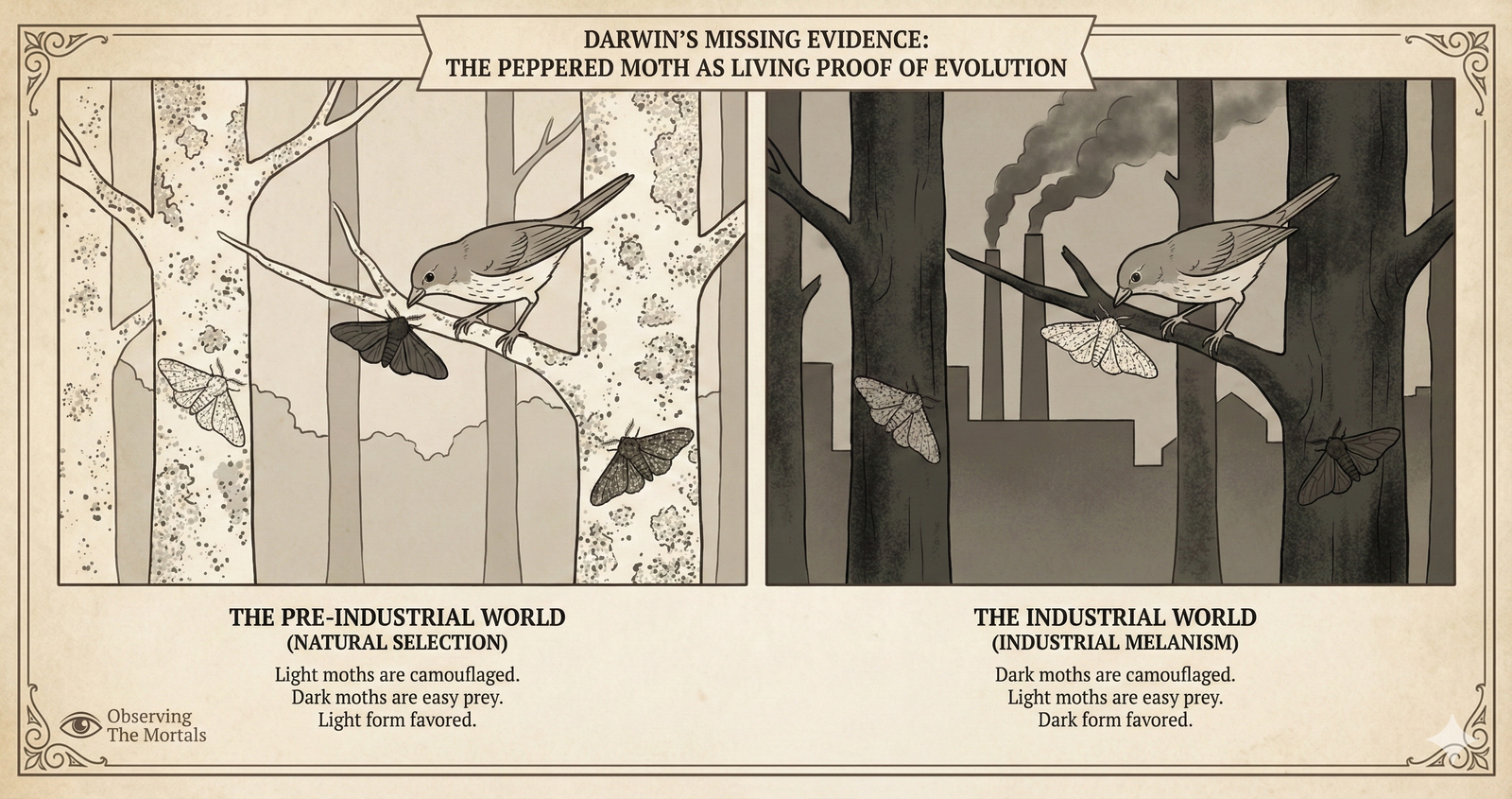

The setting is mid-20th-century industrial Britain. The key actor is British lepidopterist (moth expert) Dr. H. B. D. Kettlewell. The central mystery was a phenomenon known as “industrial melanism”: the common peppered moth (Biston betularia), which had for centuries been a light, speckled “peppered” color (typica), was being rapidly replaced by a new, jet-black variant (carbonaria) in and around industrial cities. The reigning hypothesis, championed by Kettlewell’s mentor E.B. Ford, was that the soot-covered trees no longer camouflaged the light moths, making them easy prey for birds, while the new black form was now perfectly hidden.

The Core Argument: Why This Study Matters

Kettlewell’s experiments in the 1950s provided the first direct, experimental proof of Darwinian natural selection in the wild.

- The Hypothesis: The core hypothesis was that bird predation was the selective agent driving the change. In unpolluted forests, light-colored lichens on trees provided perfect camouflage (cryptic coloration) for the light typica moths, making the black carbonaria moths easy targets. In polluted industrial forests, the soot killed the lichens and blackened the bark, reversing the advantage.

- The Experiment (Mark-Release-Recapture): To test this, Kettlewell conducted two brilliant mirror-image field experiments:

- Polluted Woods (near Birmingham): He marked and released hundreds of both light and dark moths. When he recaptured them days later, he found that 27.5% of the dark moths had survived, while only 13.0% of the light moths had. The dark moths had a 2-to-1 survival advantage.

- Unpolluted Woods (Deanend): He repeated the experiment in a clean, lichen-covered forest. The results were a perfect reversal: 13.7% of the light moths were recaptured, compared to only 4.7% of the dark moths.

- The Conclusion: The results were undeniable. In a polluted environment, birds were selectively eating the conspicuous light moths, allowing the camouflaged dark moths to thrive and pass on their genes. In a clean environment, the exact opposite happened. This was natural selection—in action, observable, and measurable.

The Anthropologist’s Gaze: A Critical Perspective

- A Perfect “Natural Experiment”: An anthropologist studying human-environment interaction would see this as a perfect, albeit unintentional, “natural experiment.” The Industrial Revolution was the independent variable (the change in the environment), and the moth population’s color frequency was the dependent variable (the effect). It’s a classic case study in cultural ecology, where a human cultural activity (industrialization) directly altered the physical environment, which in turn set a new course for the biological evolution of another species.

- The Anthropology of Science (The Controversy): The subsequent controversy over Kettlewell’s methods is a fascinating case study in the sociology of science. Critics, often motivated by creationist beliefs, attacked the methodology (such as using dead, pinned moths in some photos) to try and discredit the entire conclusion. This demonstrates a key anthropological insight: scientific facts are often attacked not on the basis of superior evidence, but for ideological, political, or social reasons.

- The Smoking Gun: Modern Genetics: The ultimate vindication of Kettlewell’s work came decades later with genetic analysis. Scientists were able to pinpoint the exact genetic mutation responsible for the black carbonaria form—a large “jumping gene” insertion—and even date its origin to around 1819, precisely at the dawn of the Industrial Revolution. This provided the final, molecular-level proof that Kettlewell’s observations were a real-time example of genetic adaptation.

The Exam Angle: How to Use This in Your Mains Answer

- Types of Questions Where It can be Used:

- “What is natural selection? Explain its operation with a suitable example.”

- “Discuss the concept of ‘industrial melanism’ as an example of natural selection in action.”

- “Analyze the role of environment as a selective force in evolution.”

- Model Integration:

- On Natural Selection: “The most famous and direct demonstration of natural selection in action is the case of ‘industrial melanism’ in the peppered moth, Biston betularia. H.B.D. Kettlewell’s classic 1950s experiments provided quantitative proof that in polluted forests, the dark carbonaria form had a 2-to-1 survival advantage because it was better camouflaged from bird predators.”

- On Human-Environment Interaction: “Human cultural activities can become powerful selective pressures on other species. The industrial melanism of the peppered moth is a prime example. The soot from the Industrial Revolution (a cultural change) altered the forest environment, which in turn made bird predation a selective agent that favored the evolution of the dark-colored moth.”

- To show modern knowledge: “While Kettlewell’s original mark-release-recapture experiments were foundational, the theory was definitively confirmed by modern genetics. Scientists have now isolated the specific ‘jumping gene’ mutation responsible for the melanism and dated its origin to the early 19th century, providing a complete picture from genetic cause to ecological effect.”

Observer’s Take

Kettlewell’s work on the peppered moth is more than just a clever experiment; it is a profound and elegant validation of Darwin’s grand theory. It transformed evolution from a slow, historical hypothesis into a fast, visible, and undeniable force that can reshape the biological world within a single human lifetime. It’s a powerful story of adaptation, but also a sober warning. It demonstrates that our own cultural activities—in this case, the pollution from our factories—are one of the most powerful and relentless selective forces on the planet, with the power to change the very color of life around us. As Kettlewell himself noted, had Darwin seen this, he would have “witnessed the consummation and confirmation of his life’s work.”

Source

- Title: “One Of The Most Beautiful Experiments In Evolutionary Biology”: What The Peppered Moth Taught Us About Evolution

- Author: Dr. Katie Spalding

- Publication: IFLScience