For decades, the story of malnutrition in India’s tribal regions has been a persistent tragedy. Now, the Bombay High Court has used words like “horrific” and “extremely casual” to describe the government’s failure to prevent the deaths of infants in Maharashtra’s Melghat region. This is not a new or sudden crisis; it is a systemic failure that has persisted for over two decades despite numerous court orders. This case study is a stark, real-world examination of the catastrophic gap between government policy, bureaucratic accountability, and the lived, tragic reality for Adivasi communities.

The Information Box

Syllabus Connection:

- Paper 2: Chapter 6.1 (Problems of Tribal Communities: Health, Nutrition, Exploitation), Chapter 6.2 (Tribal Administration, Governance Failure)

- Paper 1: Chapter 9.6 (Medical Anthropology: Critical Medical Anthropology, Health Systems), Chapter 9 (Applied Anthropology: Policy Evaluation)

Key Concepts/Tags:

- Medical Anthropology, Applied Anthropology, Governance Failure, Structural Violence, Malnutrition, Tribal Health, Melghat, Bombay High Court

The Setting: Who, What, Where?

The setting is the Bombay High Court, which is hearing petitions regarding the persistent, high rates of infant malnutrition deaths in the Melghat tribal region of Amravati district, Maharashtra. The court is directly confronting the Maharashtra and Union Governments over their “extremely casual” approach. The immediate trigger for the court’s anger is the fact that 65 infants (0-6 months) have died from June to October 2025 alone, and a 2001 court order to build a multispecialty hospital has still not been implemented.

The Core Argument: Why This Study Matters

This is not just a legal or administrative issue; it is a profound case study in the failures of applied anthropology and development.

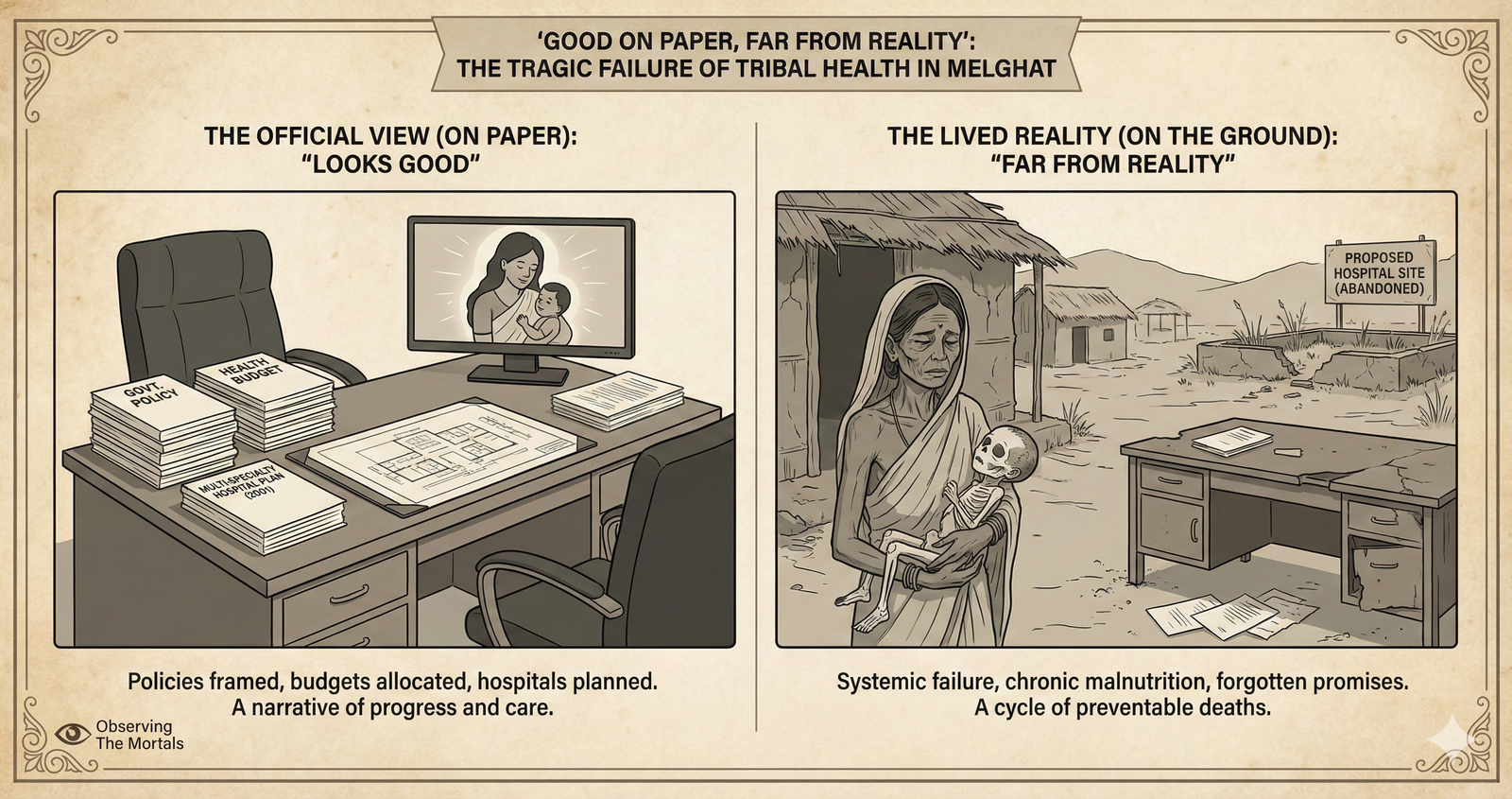

- “Good on Paper, Far from Reality”: This single quote from the High Court is the central thesis of the entire case. The court noted that the government’s documents look good, reflecting efforts and policies taken. But the on-the-ground reality—65 infant deaths—is “far from reality.” This highlights the critical, and often fatal, gap between policy formulation and policy implementation, a core theme in applied anthropology.

- Medicalizing a Systemic Failure: The government’s claim that the deaths were due to “pneumonia and not malnutrition” is a classic example of medicalisation. It attempts to frame a deep, systemic issue (chronic malnutrition, poverty, lack of healthcare access) as a simple, immediate clinical problem (a lung infection). An anthropologist would argue that malnutrition is the underlying co-morbidity that makes pneumonia lethal in the first place. The court rightly saw through this, focusing instead on the systemic failure.

- Structural Violence in Action: The problem has persisted since 2001. The court’s order to build a hospital has been ignored for 24 years. This is not just neglect; it is a textbook example of structural violence. The infants are not just “dying”; they are arguably being allowed to die by a system that has repeatedly failed to provide the basic, promised resources. Their deaths are a predictable, preventable outcome of their marginalized position.

The Anthropologist’s Gaze: A Critical Perspective

- A Critique of the “Local State”: A critical anthropologist would analyze this as a failure of the “local state.” The court is attempting to pierce the veil of bureaucratic indifference by demanding accountability from the highest levels (the Principal Secretaries of Health, Tribal Affairs, WCD, and Finance). It exposes how the administrative machinery on the ground, which is the “face” of the state for tribal communities, has failed in its primary duty.

- The “Serious-less” Approach: The court’s diagnosis of a “serious-less” and “extremely casual” approach is a powerful one. It suggests that the problem is not a lack of knowledge or resources, but a lack of political and administrative will. The lives of tribal infants are not being prioritized. This is a crucial distinction between “policy failure” and “implementation failure” rooted in systemic apathy.

- The Need for Applied Anthropology: This case is a cry for the very skills an applied anthropologist offers. A genuine solution would require not just judicial orders, but deep ethnographic engagement to understand the on-the-ground blockages. Why wasn’t the hospital built? How are the local health systems actually functioning (or not functioning)? What are the specific cultural and social barriers to access? The state’s “on paper” solutions are clearly missing this essential ground-truth.

The Exam Angle: How to Use This in Your Mains Answer

- Types of Questions Where It can be Used:

- “What are the major problems faced by tribal communities in India, especially in health and nutrition?”

- “Critically evaluate the functioning of tribal development programs and administrative bodies.”

- “Discuss the concept of ‘structural violence’ with suitable ethnographic examples.”

- Model Integration:

- On Tribal Health (Paper 2): “The health and nutritional status of tribal communities remains a critical issue, often due to severe governance failures. The recent Bombay High Court intervention in the Melghat malnutrition deaths, which the court called ‘horrific,’ is a stark example of a systemic failure, where, as the court noted, the situation ‘looks good on paper, but is far from reality’.”

- On Structural Violence: “The concept of structural violence is evident in the persistent, preventable malnutrition deaths in tribal areas. The Bombay HC’s recent critique of the ‘extremely casual’ state approach in Melghat, a problem persisting since 2001, shows how systemic indifference and the non-implementation of policies create lethal outcomes for marginalized groups.”

- On Applied Anthropology: “The failure in Melghat highlights the gap between top-down policy and on-the-ground reality. It underscores the need for an applied anthropological approach that goes beyond bureaucratic reports to understand the real-world implementation failures and socio-cultural barriers that prevent schemes from saving lives.”

Observer’s Take

This court’s intervention is a powerful, if tragic, moment of truth. The phrase “Everything looks good on paper, but far from reality” is perhaps the single most concise and devastating critique of tribal development in India today. It’s not a new policy that is needed; it is a fundamental dose of political will and accountability. This case is not about a medical crisis; it is a moral and administrative one, rooted in a “serious-less” approach to Adivasi lives. It is a powerful reminder that an administrator’s most important job is to close the fatal gap between the promise on paper and the reality on the ground.

Source

- Title: Bombay HC criticises govt. over malnutrition deaths in Maharashtra’s tribal regions

- Author: Snehal Mutha

- Publication: The Hindu (based on layout and byline)