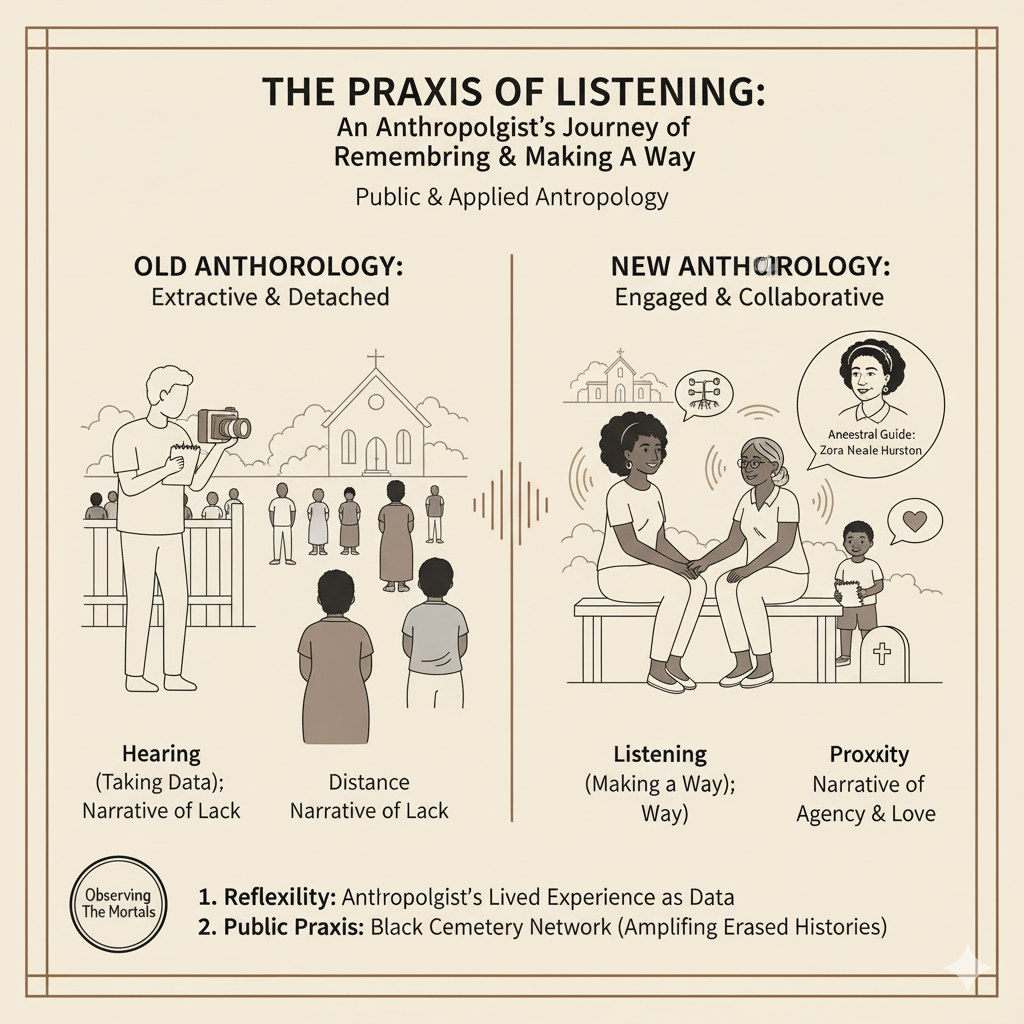

In our current, often turbulent moment, how do we even begin to imagine a better future? In her powerful 2024 keynote address to the American Anthropological Association, Dr. Antoinette Jackson offers a profound answer: we begin by truly and humbly listening to the past. This is not a story of grand theories or abstract data, but a deeply personal journey through family histories, plantation landscapes, and the forgotten graves of ancestors. It is a masterclass in a different kind of anthropology—one that is engaged, public, and rooted in what she calls “the art of remembering and making a way.”

The Information Box

Syllabus Connection:

- Paper 1: Chapter 9 (Applied and Action Anthropology), Chapter 1.8 (Research Methods: Reflexivity, Fieldwork Ethics), Chapter 12 (Postmodernism in Anthropology)

- Paper 2: Chapter 7 (Role of Anthropology in Tribal/Community Development), Chapter 1.1 (Indian Civilization – provides comparative context for public archaeology)

Key Concepts/Tags:

- Praxis, Applied Anthropology, Public Anthropology, Reflexivity, Zora Neale Hurston, Black Cemetery Network, Decolonizing Methods

The Setting: Who, What, Where?

This case study is an analysis of the keynote address, “The Art of Remembering and Making a Way,” delivered by Dr. Antoinette Jackson, a leading public and applied anthropologist. The essay is a work of reflexive anthropology, where Dr. Jackson uses her own life and career—from her childhood summers in Louisiana to her extensive applied work with the US National Park Service and her current project, the Black Cemetery Network—as the primary data to articulate a powerful call to action for the discipline. The intellectual guiding star of her work is the great anthropologist and author Zora Neale Hurston.

The Core Argument: Why This Study Matters

This is a profound argument for a more engaged, ethical, and publicly relevant anthropology, built on a “praxis of listening.”

- Challenging the “Narrative of Lack”: Dr. Jackson argues that the stories of marginalized communities have too often been framed by outsiders from a perspective of “lack, deficit, and marginalization.” Her own upbringing, rich with family stories of pride and agency, taught her to reject this. Her work seeks to replace this narrative with one that centers the agency, knowledge, power, and love of the people themselves.

- Listening as a Transformative Method: The central methodological argument is that true anthropological understanding comes not from “hearing” what people say, but from actively and humbly “listening.” She uses her own jarring experience with Ms. Mattie Gaillard—a descendant of enslaved people who considered a plantation “home”—to show how an anthropologist must be willing to “release their own fixed ideas” to learn from the complex, lived realities of the community.

- “Doing” Anthropology in the Public Sphere: The essay is a powerful call for anthropologists to move beyond the walls of academia. Her career is a testament to this, using her expertise to directly reshape public narratives at National Park sites. Her current work with the Black Cemetery Network is the ultimate example of “doing” anthropology—creating a tangible, public, and community-driven platform to bring dignity to erased histories.

- Reclaiming an Ancestral Lineage: A key part of her praxis is the active reclamation of Zora Neale Hurston as a central figure in the anthropological canon. She argues for embracing Hurston’s method of using personal experience and seeing the world “through the community’s eyes,” a direct challenge to older, detached models of “objective” research.

The Anthropologist’s Gaze: A Critical Perspective

The entire essay is a critical perspective on the discipline itself, offering several key analytical frames.

- A Model for Reflexive and Postmodern Anthropology: Dr. Jackson’s method is a masterclass in reflexivity. She is not an invisible narrator. She places herself, her family history, her moments of ignorance, and her epiphanies at the center of the story. This is a key tenet of postmodern anthropology, which rejects the idea of a neutral, all-knowing observer and instead embraces the researcher’s subjective position as part of the analysis.

- The Anthropologist as Public Servant: Her work fundamentally redefines the role of the anthropologist from a “lone scholar” to a public servant and facilitator. Her journey is a series of powerful lessons in this:

- “What is missing?” (Jehossee Island): The anthropologist’s job is to find and amplify the erased histories.

- “Tell them we were never sharecroppers” (Snee Farm): The anthropologist’s job is to challenge dominant, monolithic narratives.

- “Do your homework” (President Carter): The anthropologist’s job is to earn the community’s trust through deep, rigorous fieldwork.

- “I am not sure I can help you” (Dr. Cole): The anthropologist’s job is to approach the community with humility and a clear purpose.

- A Critique of Extractive Research: Implicitly, the entire essay is a powerful critique of an older, extractive model of anthropology, where researchers would “take” data from a community for their own academic careers. Dr. Jackson’s praxis is about collaboration, giving back, and creating lasting community resources like the Black Cemetery Network.

The Exam Angle: How to Use This in Your Mains Answer

- Types of Questions Where It can be Used:

- “What is the significance of reflexivity in modern anthropological research?”

- “Discuss the role and ethical responsibilities of an applied anthropologist.”

- “How have postmodernist critiques changed the way anthropology is practiced?”

- Model Integration:

- On Reflexivity: “Reflexivity in anthropology involves the researcher critically examining their own position and biases. Dr. Antoinette Jackson’s keynote address, ‘The Art of Remembering and Making a Way,’ is a powerful example, where she uses her own life story and moments of personal learning to articulate a more ethical, community-centered praxis.”

- On Applied Anthropology: “The role of an applied anthropologist is not just to study a community, but to serve it. Dr. Antoinette Jackson’s work, from reshaping narratives at National Park sites to creating the Black Cemetery Network, exemplifies a praxis where anthropological skills are used to amplify erased histories and create tangible public resources.”

- On Postmodernism: “Postmodern critiques have pushed anthropology to move beyond grand, objective narratives. The work of public anthropologists like Antoinette Jackson, inspired by figures like Zora Neale Hurston, emphasizes listening to nuanced, local stories and seeing the world ‘through the community’s eyes,’ thereby challenging older, top-down models of research.”

Observer’s Take

Dr. Antoinette Jackson’s keynote is a powerful and deeply moving call for a more human and more humane anthropology. It is a journey that reminds us that the most profound lessons are learned not in the library, but in the quiet moments of listening—to an elder’s story, to a community’s plea for recognition, to the silent testimony of a forgotten grave. Her work is a testament to the idea that anthropology, at its best, is not just the study of humanity, but an act of service to it. It is a call to action for every student of the discipline to accept their role not just as observers, but as witnesses, storytellers, and active “way-makers” in the ongoing project of bringing dignity and voice to those who have been silenced.

Source

- Title: The Art of Remembering and Making a Way: Going There, Knowing There, and Other Curious Lessons From “The Genius of the South”

- Author: Antoinette Jackson

- Publication: American Anthropologist (2025)

- Link: https://doi.org/10.1111/aman.70027